Thirty-five years ago this January, President Jimmy Carter offered unconditional amnesty to Americans who had evaded the Vietnam-era draft. Three years earlier, President Gerald Ford had extended conditional amnesty to the tens of thousands of Americans, both draft dodgers and deserters, who had entered Canada from 1962 to 1973—a period when shifting immigration policies muddied the waters between legal and illegal entry. Having avoided the fate of 60,000 of their countrymen, many (some estimate more than half) stayed, making Canada their permanent home.

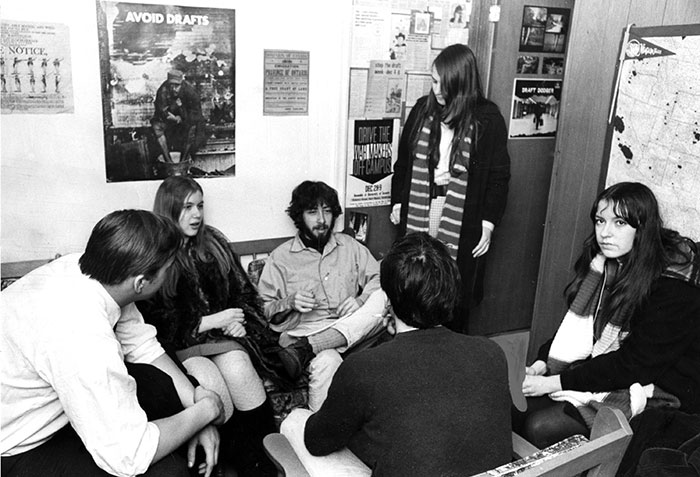

John Swalby, a deserter who grew up in Wisconsin and then Albuquerque, was one of them. After graduating from high school in 1967, he enlisted in military service and was eventually sent to El Paso, Texas, to study Vietnamese. During a visit home for Christmas, he saw a high school friend who had since become involved with Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). “They got to talking to me and convincing me what I was doing was really, really wrong,” he told interviewer Stephen Maxner thirty-four years after the fact. In March of 1968, he fled to Toronto, where he would spend the following twenty-two years, relocating to Vancouver in 1989. The following is an excerpt from their telephone conversation, recorded for the Vietnam Center and Archive at Texas Tech University on March 19, 2001.

The language school was kind of a funny place. We were in an environment of saturation learning, no English allowed… We weren’t faring too well, mentally. There was a class of twenty-seven of us. A couple of guys had just committed suicide, the time shortly before I arrived. Two more guys escaped in probably February or so. They made it as far as Minnesota or Montana, somewhere up there. One guy killed himself rather than be taken alive. The other guy, they hauled back. There was another suicide, a young Spanish guy. He had just come back from Vietnam, re-enlisted and they gave him Vietnamese language school. So he did himself in, right away. I don’t know what it was about the mental attitude of all us young kids in those days. The fact that we were going there—it’s just, your whole future is just gone.

***

***

As it turns out, the people who were organizing this, they had a very well-organized network of information through the university systems. They said at the last second, no, we’re putting you on a plane to Buffalo. So they smuggled me up from Albuquerque to Buffalo, gave me a fake ID, gave me a fake draft card, put money in my pocket, and put me on a plane to Buffalo. They gave me a phone number to call. They said this guy will meet you in Buffalo.

He met me at the airport. He says, “John, we’re going to drive across the border. Have a cup of coffee. Look at the Falls, and don’t say nothing to the border guard.” So he drove me right from the airport, right across the bridge at Fort Erie, and I was in Canada. He basically put me on a bus to Toronto. He gave me a phone number and an address.

***

An incredible peace comes across your mind [crossing the border]. I was sitting on the banks of the Niagara River at Fort Erie, waiting for the bus, watching the ice flow, looking at the green parkland of the Fort Erie side of the river, looking back at the squalor in Buffalo, thinking, hmmm. From then on, I think this was a good decision.

No Quarter

Military deserters still come north, but they now face deportation

Operational Bulletin 202 is a directive to Canadian immigration officers, issued in July 2010, instructing them to flag refugee claims by American military deserters, who have very rarely been granted refugee status since the Harper government took power. In September, the War Resisters Support Campaign, which provides deserters with legal and practical advice, hosted a conference to help raise awareness about the cause, featuring a panel of three Iraq war veterans: two men and a woman, a mother of small children. Thirty people, mostly family and friends, along with several Vietnam veterans, listened as the panel described their experiences: they could no longer in good conscience buzz or bomb non-threatening civilian targets. They all face deportation from Canada to the US, then courts martial, followed by indeterminate sentences in military prison.

—Bronwen Jervis

This appeared in the December 2011 issue.