It’s a big year for anniversaries in the Anglosphere. At the Battle of Agincourt, in 1415, a small and dysentery-ridden English army defeated a massive and well-fed French force on their home territory. Band of brothers and all that, made famous by Shakespeare, Laurence Olivier, and Kenneth Branagh. It was indeed a remarkable victory and made the longbow famous. Which is why many people ask: “Why didn’t the French have them too? ” The short answer is that it took years of training to use a longbow properly; much easier to give crossbows to thousands of raw peasants, but nowhere near as effective or easy to reload. In any event, all of the gains made at Agincourt were lost to the French fairly soon afterwards. Plus, Henry’s son and heir was a pious halfwit who was almost certainly murdered by his rivals.

Four hundred years later, in 1815, came the Battle of Waterloo. Contrary to British boast, even if the Duke of Wellington had lost in Belgium, another allied army would have been assembled and Bonaparte would have been defeated in round two. There simply weren’t enough Frenchmen of fighting age left.

Then there is 1215, Runnymede, King John, the Magna Carta. Surely this is the truly important one: The beginning of democracy, civil rights, representative government, the rule of law, and the balance of powers. And not just for the British. Magna Carta, it is claimed, had a profound influence of the American Revolution and Constitution, on the evolution of the British parliamentary system, and thus on the former imperial states and on countless popular political movements throughout the world. On June 15—Magna Carta’s 800th birthday—it is worth asking: What actually was it, and how did it come about?

The early thirteenth century was an unstable and dangerous time, even by medieval standards. Henry II, a strong, supremely able monarch, had reigned for more than thirty years before dying in 1189. His son Richard, lion-hearted but seldom in England, had allowed the country to thrash around in misrule. By the time his brother John came to the throne in 1199, the toxins of division, dispute, and despair were flowing into the bloodstream of the body politic. The French wanted war, the barons wanted power, the people wanted food, John wanted money.

Although the stuff of unflattering movie and literary caricature, John was an intelligent man and a capable military leader but was in an invincibly difficult position. He was, for example, prepared to stand up to Pope Innocent III—until the pontiff excommunicated him and placed the entire country under an interdict, thus withdrawing the sacraments and banning religious services. This led to the story, probably apocryphal, that John sent emissaries to Muslim leaders offering to make England an Islamic state if the Turks refilled his treasury.

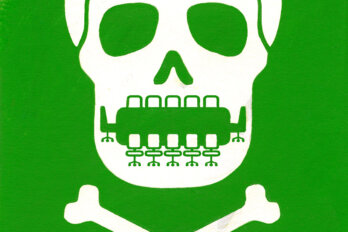

What we do know to be true is that a generation of weak monarchy had produced a power vacuum, and that the barons—a cabal of several dozen leaders of mighty clans and families—wanted to fill it. There are no good and bad guys here really; the tale is really more about different degrees of ambition. It would be 400 years before notions of democracy and genuine rule of law—as we would understand those concepts—would truly develop.

It was at this historical junction that an inner group of twenty-five barons, with the military support of the French and the Scottish, forced John to sign the Magna Carta guaranteeing the rights of the church, limiting the amount of money paid to the crown, preventing illegal arrest and imprisonment for the barons themselves, and demanding that no freeman could be punished outside of the law. It wasn’t as original as popular history has assumed, being at heart a confirmation of the Charter of Liberties from 1100. Nor did it last. As soon as the barons left town, the king renounced the document. Innocent III, with whom John had reconciled in 1213, called it a “shameful and demeaning agreement, forced upon the King by violence and fear.”

The result of all this was a civil war, the First Baron’s War, in which the Magna Carta backers tried to depose John and put their own nominee on the throne. As always, it was the common people who suffered as they were forced into armies, saw their property destroyed and their loved ones killed. And it was all for naught. John died the following year of natural causes and the Magna Carta was affirmed by his son and heir Henry III. It was to be edited and adapted several times in the following centuries, used by legal scholars to give foundation to their arguments and by reformers to bolster their agendas.

Yet a reading of the document isn’t quite as inspiring as some would have us believe. There’s a discussion of fishing rights, and a chilling clause concerning the money that could be claimed from the Jews. But there was not, as some have suggested, a guarantee as we would know it today of trial by jury or habeas corpus. Most of the language proclaiming judicial independence and fair hearings is in defense of the powerful rather than the powerless.

Nevertheless, Magna Carta at least set some limits in the king’s authority. And as a result, it would be used as a starting point, perhaps an inspiration, for further reform efforts in centuries to come. The framers of the US Constitution’s Bill of Rights, for instance, based the words “no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” on the earliest Magna Carta text.

There are only three passages from the original document that still exist in English law. One concerns the freedom of the Church of England; another guarantees the rights of the City of London and various ports; and one, the least anachronistic, states that:

No freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his freehold, or liberties, or free customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will we not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his peers, or by the law of the land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either justice or right.

“Disseised”? Nice word, which means removing a party wrongly from property that is lawfully possessed. It mattered then, it matters now.