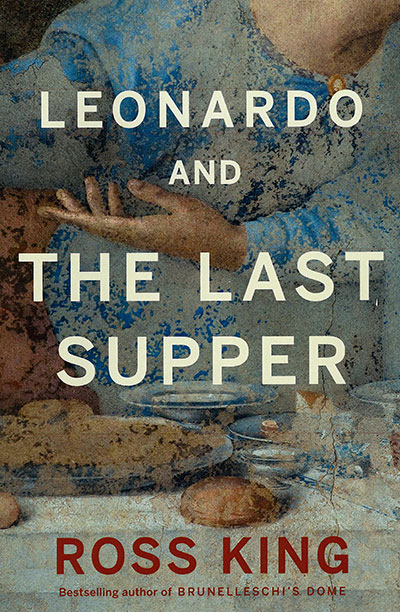

As an expert on the Italian Renaissance, Ross King is sometimes asked this baffling question: If he could go back in time, would he rather have dinner with Michelangelo or Leonardo? Deeming the former a “lugubrious, paranoid individual,” and the latter a “kind, witty courtier,” the bestselling author says the answer is obvious. King’s insight into da Vinci’s personality, and his revealing account of the turbulent political backdrop against which the master painted one of his greatest works, anchor his most recent book, Leonardo and the Last Supper.

Last night in Ottawa, King received his second Governor General’s Literary Award for English-language non-fiction, for writing Leonardo. (His first, in 2006, came for The Judgment of Paris: The Revolutionary Decade That Gave the World Impressionism.) Born in Estevan, Saskatchewan, he now lives near Oxford, England.

In Leonardo and the Last Supper, you’ve cited everything from the Bible to The Da Vinci code. Was it extensive reading?

It was. I spent more time on this work than any other of my books. I found out that Leonardo bought a Bible in the autumn of 1494, when he was starting work on The Last Supper. He wanted, literally, to get the gospel truth of what had happened between Jesus and his disciples. So it behooved me to follow in Leonardo’s footsteps and read the gospel as well. I had to investigate many of the things Leonardo had investigated 500 years earlier, including existing versions of The Last Supper.

I’m inevitably asked whether the person to the right of Christ is a male or female figure—a doubt cast by the conspiracy theory in Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code. I’ve tried to convince people that the figure is St. John—not Christ’s wife—who has crashed the supper and elbowed an apostle out of the way.

How much of this book is your own speculation or inferences?

I think speculation is inevitable when you’re writing about history, especially when that history is more than 500 years old, and the record is scanty. It’s necessary and I think it’s warranted. But it’s important to let the reader know where there is a gap in our knowledge, and then propose to fill the gap using logical inference. We simply don’t have all the evidence and records needed to state things categorically.

Some biographers are categorical. What do you make of the early writings about Leonardo?

There are some extremely good ones. Giorgio Vasari, for one, who was writing in the middle of the sixteenth century with much more evidence than we have today. But he very clearly exaggerated and made things up because his agenda was to aggrandize the artists he wrote about. I think we have to take much of what he said with a grain of salt.

Can you remember one of Vasari’s fabrications?

Vasari wrote about how Leonardo couldn’t find a model for the Judas figure. Meanwhile, the Dominican prior of the convent where Leonardo was painting had been been harassing him for taking too long to finish. The prior complained to the Duke of Milan. Leonardo responded by threatening to turn the prior into Judas in his painting. Vasari told the same story about Michelangelo painting the Sistine Chapel. They can hardly both be true.

What about the Judas story presented by the Presbyterian evangelist, J. Wilbur Chapman?

That’s a nineteenth-century invention. Supposedly, Pietro Bandinelli was a seminary and Leonardo’s model for Christ. Many years later, sinful living had turned angelic young Bandinelli’s features into the twisted, evil features of Judas. So Leonardo used the same model for both Christ and Judas. The story implies that Leonardo took ten or twenty years to paint The Last Supper; in fact, he took three years, or less.

Your book discusses other American interpretations of Leonardo’s life. What do you make of them?

One fascinating thing I’ve found is that recently, Leonardo is imagined as this swashbuckling heterosexual. Fifteenth-century sexuality is difficult to understand, but by our present standards, Leonardo was homosexual. There is evidence: his relationship with his errand boy, Salai. The two of them were almost certainly long-term lovers. Many, though not all, American popular culture references ignore this.

What surprises you about Leonardo?

We think of him as an all-encompassing genius, someone who could succeed at anything. Yet he hadn’t achieved a whole lot, even by the age of forty—and the average life expectancy back then was forty. Many of his contemporaries were dead by time he started The Last Supper. He had painted The Virgin of the Rocks, but it disappeared off the map. There was also The Adoration of the Magi, but he walked away from it within a year. In fact, he walked away from a number of commissions. The Last Supper was one thing that he did finish—almost against his nature.

Would he have rather been doing something else?

He certainly wanted to step up into the pantheon of great artists. He knew he couldn’t occupy one of those niches unless he had some kind of grand public work. When he was not finishing paintings he was happily going about trying to draw up architectural designs—a domed tower for Milan’s cathedral, for example. He was a brilliant three-dimensional geometer. Tragically, he couldn’t find any patrons for his architectural plans. Had he been able to design a building—or do anything on a large scale, he would have been much more content. He was also a hydraulic engineer, and one of history’s great anatomists.

Is there anything he didn’t excel at?

Language. He had six Latin primers in his collection—that’s like someone today with six French 101 textbooks that they’ve been through numerous times, desperately trying to learn the language.

Do you have a sense of how satisfied he was with his career, in the end?

I think he was unsatisfied. Throughout his career he was frustrated, as much as everyone else, by his inability to bring everything to completion. In his notes, he would write things like, “Tell me if I ever did a thing.” He knew he was gifted with tremendous talents, but was never able to concentrate on that one particular thing.

What about your own career, how did you become interested in art history?

Partly, it comes from Leonardo. When I was around twelve years old, I was interested in his drawings. I hoped that because I’m left-handed like Leonardo, I would be talented like him. I quickly realized that you have to be more than left-handed to be a good artist. Giorgio Vasari and his outlandish stories about fifteenth-century artists also influenced me. My interest in art history also developed from going to art museums and being interested in the story behind the paintings—what went on outside the frame.

This interview has been condensed and edited for publication.