In the whole of Anne of Green Gables, there is not a single storm, and it rains just three times. In five years. In a village on an island in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Meteorologically speaking, that’s unlikely.

Artistically speaking, it’s entirely predictable, because Anne is a pastoral, a literary genre set in the cleared space between the wilderness (the ocean, in this case) and the city. And the colour of pastoral is forever green, the green of the Cuthberts’ grass and gables.

But Anne is from the Island. Moses Sweetland, the lonely, scared, stubborn, “miserable cunt” who is the unlikely hero of Michael Crummey’s newest and greatest novel, is from the Rock. And Newfoundland literature is more often grey than green—the grey of rocks, water, and sky. Compare Anne with Norman Duncan’s The Way of the Sea, a collection of stories published in 1903, five years before Anne, and set on Newfoundland’s northeastern coast in the outport of Ragged Harbour. In the opening story, a boy of about Anne’s age follows the mystery of where the tide goes until he loses his way in the dark and drowns, his body smashed on the same rocks that killed his father. In Avonlea, the sun always shines; in Ragged Harbour, you can’t see the sun for the fog.

Anne is an idealist, a book that believes good will triumph and truth will win out. In The Way of the Sea, nothing is certain, and truth is just a story. The question of where the tide goes is but one mystery of many. “Truth,” thinks the boy, “it was like a scream in the night.” Anne doesn’t talk like that, because Anne doesn’t think like that.

Ever since The Way of the Sea was published, Newfoundland literature has generally been more inclined to stony skepticism than sunny idealism. So has most modern literature, or at least the kind we call “literature,” the kind we call “modern.” But Newfoundland’s version of the modern turn seems especially marked by a sense of life as random, unshaped by meaning. Maybe it’s the weather. Or maybe it’s living in a place that has twice voted itself out of existence, forcibly resettled thousands of its people, and lost thousands more to jobs on the mainland. As one of Duncan’s characters says, “They’s noa such thing as harbour.” It must be hard to feel at home, when home keeps changing around you.

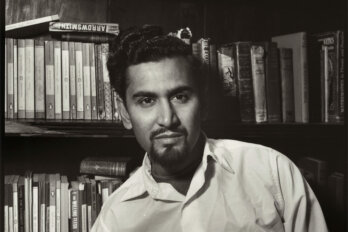

The way it does in Michael Crummey’s novels. In his first, River Thieves (2001), a boy trying to make shore in a storm sees the land appear and disappear behind the waves like “a promise of shelter offered and then withheld, offered and withheld.” Crummey is a contemporary of the Burning Rock Collective, the St. John’s writers group that includes Michael Winter, Jessica Grant, and Lisa Moore, and injected a dose of urban realism into Newfoundland literature, moving fiction out of the outports and into town, away from the cod and the fog and the dories. Crummey went the other way, making his name with a historical romance set on the island’s remote north coast in the early nineteenth century.

Though Crummey’s books differ from those of the Burning Rock group in form and content, they’re philosophically kin. At the heart of River Thieves is a mystery, a question that never really gets answered. People die, and we learn who killed them; but not why, or what it means. His second novel, The Wreckage (2005), is a love story based on a lie, a romance that ends with a wedding conducted by a senile old lady dressed up as a priest, saying words in Latin that the bride can’t understand and the groom no longer believes. In Galore (2009), the discovery of a man in the belly of a beached whale provokes among those who find him “the consensus that life was a mystery and a wonder beyond human understanding,” a consensus the novel does nothing to dispel. (If there are answers beyond human understanding, we don’t hear them, either. As Galore’s priest says, “God give up talking to such as we a long time ago.”)

This summer, Crummey published his fourth novel, Sweetland. It’s about the life and presumed death of Moses Sweetland, a sixty-eight-year-old former fisherman put out of work by the cod moratorium in 1992, and again by the automation of the local lighthouse, of which he was the last keeper. As part of an ongoing resettlement program, the Newfoundland government will pay each household on the island of Sweetland at least $100,000 to relocate, but only if everybody takes the deal. Moses is the last holdout, left behind like his namesake to die without his people, and the only living character on the island in the second half of the book.

Crummey’s novels have tended to be crowded with stories and characters, maybe because he grew up in small communities in which everybody knows everybody else, and their stories. (Novels by urbanites are more solitary, driven inward by the solipsism it takes to survive cities too big to know.) This time, he’s picked a story about a community that loses all its population but one: Moses, his most memorable character yet, an East Coast Hagar Shipley, with good odds to become as much of a CanLit icon.

Sweetland is also Crummey’s first novel set in contemporary Newfoundland, his first that’s not a historical romance—unless you’re young enough to think of 2012 as history. It’s still a romance, still the kind of story in which coincidence matters as much as or more than cause, and the characters are the best or worst of their kind; the strongest or, in this case, the most stubborn. It’s not romantic in the Harlequin sense (Moses wipes his ass with those, after he runs out of toilet paper). And it’s not romantic in the magical realist sense, the way Galore was romantic, with living men emerging from dead whales. In fact, Sweetland tries to read a book about Newfoundland that sounds a lot like Galore, but gives up and throws it in the ocean, thinking that whoever wrote it “didn’t know his arse from a dory…and had never caught or cleaned a fish in his life.” (Crummey says the book was actually referred to as Galore in an early draft, as a way of letting the “real” Newfoundland reject fictional versions of itself, including his own.) Sweetland is romantic in the way a Christopher Pratt painting is romantic, where the real is romantic enough, especially in a place like Sweetland—with a boy who talks to the dead, or a woman who hasn’t left her house in forty years because she couldn’t see the point after getting indoor plumbing.

Home is just as hard to find. The novel is about a man who stays home and loses it anyway, a lighthouse keeper with no one left to keep. It opens with voices in the fog, voices only much later identified as Sri Lankan migrants adrift in the Atlantic, more homeless characters to add to Crummey’s growing cast of foundlings. In his sermon about the Sri Lankans, Sweetland’s philandering minister asks the congregation to imagine themselves in their position, “orphaned on an ocean that seems endless.…We could see it as a metaphor, the Reverend said, for our own place in the universe.” Of all the Reverend’s sermons, that’s the only one Moses remembers.

Crummey’s first novel used epigraphs from the Dictionary of Newfoundland English, and his books and many others from the island are strewn with local vocabulary and turns of phrase, words that mark these stories as their own. Maybe Newfoundland has its own dictionary because words matter more when they refer only to the world before you, when the truth is just a story. Moses Sweetland clings to sanity at nights by naming local landmarks in his head, “as though the island was slowly fading from the world and only his ritual naming of each nook and cranny kept it from disappearing altogether.” Later, he adds place names, both real and invented, to a map of Newfoundland. He enacts Sweetland’s first epigraph, from Isaiah: “Even unto them will I give in mine house and within my walls a place and a name.”

Moses’s island later disappears from his map, as if he had imagined it. When he looks down at the ocean one night, he sees “nothing below but a featureless black, as if the ocean was rising behind him and had already swallowed the cove and everything in it.” But it hasn’t, and it won’t—not as long as people keep reading the book that imagined it. “A story is never told for its own sake,” says John Peyton Jr. in River Thieves. When stories are all you’ve got, stories matter.

This appeared in the October 2014 issue.