You can tell Wayne Alfred is at work by the smoke rising from the stovepipe above his Cormorant Island carving workshop, on the shores of Alert Bay. When I visit, tables, tools, and books are all out in the open air. Alfred and his four Kwakwaka’wakw apprentices are taking advantage of the long August evenings. Wood shavings blanket the ground, burying various books splayed open to photographs of totem poles and ceremonial masks for inspiration.

The carvers take a short break to gather around my iPad and look at some of Canada’s oldest documentary footage of the Far North—older, even, than Nanook of the North, which is held up as the quintessential classic in Canadian film circles. The material Alfred is watching was shot in Alert Bay for the Hudson’s Bay Company’s 250th anniversary in 1920, long before the fifty-four-year-old carver was born. For six months, a film crew visited fur trade outposts across Canada, travelling by company steamer, kayak, canoe, even dogsled. The Romance of the Far Fur Country played in cities across western Canada, and across the pond in London, where the reels of nitrate film were squirrelled away at HBC’s then headquarters.

Later, the collection was moved to the British Film Institute Archives, where I first encountered it. While winding the reels onto a Steenbeck viewing machine, my brother and I hatched the idea of taking the footage back to the communities where it was shot. Two years later, the Return of the Far Fur Country project arrived in Alert Bay.

Before starting our journey, we had been prudently warned by academics and advisers that this was culturally sensitive material; HBC, after all, was a colonial venture. I keep this in mind as the first shots of Alert Bay appear onscreen, the iris of the camera opening around a totem pole with a raven’s beak cut from half a canoe.

“That’s my grandfather’s house,” Alfred says, tapping the screen with a blue drafter’s pencil. He examines the Wakas Pole—once owned by his grandfather, Moses Alfred—sold first to Vancouver’s Stanley Park in the 1920s, and then to the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Ottawa in 1986. Today it stands in the museum’s Grand Hall, restored by one of Alfred’s mentors, Doug Cranmer.

As the camera pans across the Alert Bay shorefront, Alfred matter-of-factly names each family pole with a point of his pencil. “This is Dan Cranmer’s house. This one here belongs to Johnny Drabble. And this one belongs to Joe Harris.”

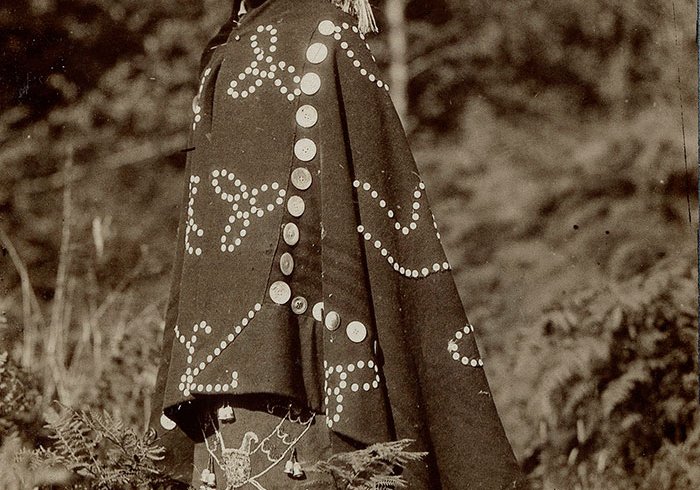

The camera moves to the people of Alert Bay. “That guy looks familiar,” says Alfred, shaking his head, trying to remember. “He looks like one of my family members.” The youth is dressed for a potlatch. When he turns around to show the full display of his cloak for the camera, Alfred lets out a satisfied laugh. “Yeah, see? That’s a Tree of Life. That’s one of our crests.”

Later that evening, a roomful of Kwakwaka’wakw people, many from Alert Bay’s own ‘Namgis First Nation, gather at the U’mista Cultural Centre for a public screening. Watching at the back of the room, I am struck for the first time by the full weight of one inter-title: “Here family trees grow well.” Afterwards, ‘Namgis chief Bill Cranmer introduces himself as the great-great-grandson of Mary Ebbetts, a Tlingit woman who married Robert Hunt, an HBC factor who emigrated from England. “My family is very closely tied to the Hudson’s Bay Company,” says the seventy-four-year-old elder.

Chief Cranmer grew up during Canada’s potlatch ban, which lasted from 1884 to 1951. His father, Dan Cranmer, is credited with throwing one of Alert Bay’s largest and most infamous potlatches, in 1921. The RCMP later cracked down on the practice, arresting Dan Cranmer and others. They also forcibly removed masks and other potlatch regalia; many of these articles ended up in the same museum as the Wakas Pole, in Ottawa.

Community leaders have been working to repatriate the artifacts ever since, eventually building the U’mista Cultural Centre in 1980 to house them. The Potlatch Collection now decorates the main hall, having been returned after long interludes at the British Museum, the Smithsonian, and other institutions.

Trevor Isaac works in collections and education at U’mista. When I meet up with him the following day, he has dug out binders of photographs from the centre’s archive to help him match photos to the 1919 footage I have loaded on my iPad. “Lots of things have been lost due to the potlatch ban and the residential schools,” he says, “but we’re pretty lucky because of all the anthropologists and visitors. Our history is well recorded.”

One inter-title has misidentified a carving as a Thunderbird. “It’s not a Thunderbird; it’s a Huxwhukw,” he explains. Pausing and playing back the segment, he finds two other poles that actually are Thunderbirds. Like the Wakas Pole Alfred pointed out, the two on the screen were moved after they were first filmed; a decade later, they marked the entrance to Alert Bay’s residential school, a four-storey building that still towers over the diminutive wooden cultural centre.

But only in the most literal sense. Most of the school’s windows are broken. The flaking white paint reveals red brickwork underneath. The metaphor is not lost on Isaac or me. One Thunderbird, itself in a state of decay, remains by the school, on the grounds of U’mista. Grass grows from the top; its twin fell down a few years ago. This process of disintegration, though, is acknowledged and accepted in ‘Namgis tradition. “It’s the cycle of things,” Isaac says.

In the distance, behind U’mista, I notice smoke trickling from a stovepipe: Alfred and his apprentices are back at work, carving the next generation of poles.

Dream Escape: Recovering Walter Benjamin’s magnum opus

Shen Plum

In late September 1940, the German Jewish critic Walter Benjamin crossed the Pyrenees to escape occupied France. Though he suffered a heart condition and walked slowly, he carried a heavy black briefcase containing a manuscript. “I cannot risk losing it,” he told his guide. “It is more important than I am.” For more than a decade, Benjamin had examined the glass-roofed inner corridors of the Paris arcades, sifting through “the rags, the refuse” to capture the “phantasmagorias” of nineteenth-century bourgeois life and awaken readers to “that dream we name the past.” He was denied entry to Spain and, overcome with despair, took an overdose of morphine, and then the manuscript mysteriously disappeared. Shortly after the war, though, a copy of The Arcades Project was recovered in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, hidden years earlier by Benjamin’s friend Georges Bataille. The corpus would eventually be recognized as the author’s magnum opus.

—Julien Russell Brunet

This appeared in the December 2012 issue.