Fourteen years ago, Virginia Champoux began using the Internet as her diary. The then-thirty-two-year-old Montrealer created a blog to track her experiences with infertility. Then, shortly after travelling to Beijing to adopt the first of her two Chinese-born children, she joined an adoption message board to share her daily ups and downs with other prospective mothers. Eventually, she started blogging about her experience with breast cancer. When Facebook came online in 2004, Champoux became an active user. “The site was an organizing principle for my entire emotional, intellectual, and social life,” she says. “It was how I communicated with everyone I knew. Why make the same phone call fifteen times?”

In 2012, when Champoux’s husband, Jay, received a lung transplant, her social-media usage jumped to another level. Facebook became her daily—often hourly—outlet for sharing the agonizing, surreal, and occasionally funny details of Jay’s struggle to survive. Surf Champoux’s page, and you’ll find brutally candid descriptions of her husband’s psychotic response to medication (he sometimes would accuse people around him of being spies) and his penchant for ordering odd products online (such as a windbreaker with built-in pillow and stylus), as well as photos of his diet (in one image, he’s digging into veal purée).

There appeared to be few no-go subjects. “Nobody ever wants to write a status update about their spouse’s digestive tract,” Champoux wrote in one post, “but several of you kind people were worried about yesterday’s giant step up to solid food. I’m happy to report that Jay Sokoloff’s innards have resumed their normal work.” In another, much darker moment: “Everyone is so fucking optimistic, but I just can’t be. It’s not that I don’t want things to go well. Seriously, I want nothing more. But I just can’t find a way to believe anymore.”

Jay died this past January, a year after a second lung transplant. During his last months, relations became strained between Champoux and her in-laws, some of whom believed that she’d become fatalistic about Jay’s condition. In one tense episode, there was a confrontation outside the intensive-care ward—and security guards came to escort the visitors out. On Champoux’s own Facebook page, one in-law suggested that Champoux might actually be conspiring to hasten Jay’s demise: “We all care and love Jay Sokoloff and hope for his speedy recovery, however the question is how sincere are you? . . . Is there something that Virginia Champoux Sokoloff is hiding? Perhaps something is in the offing?”

“I deleted the post but took a screenshot first,” Champoux tells me. “If you can believe it, the guy who posted that actually tried to show up at my house for the shiva.”

The period that Champoux spent Facebooking her husband’s medical saga occurred at a time of growing concern about the way tech companies handled our personal data. Five years ago, Facebook was accused by the United States government of deceiving users—by leading them to believe their information was protected while at the same time allowing access to third-party software makers, unilaterally sharing private data with advertisers, and even permitting surfers to view photos and videos from deactivated accounts. Other Silicon Valley giants confronted similar controversies. In 2012, Twitter was caught storing personal information from user address books, and Google paid a $22.5 million fine for secretly installing tracking cookies on Apple’s Safari browser that bypassed privacy settings. The media took notice of the public mood. Breathless reports on “The End of Privacy” became a news staple, and bestselling titles from the period include No Place to Hide, Privacy in Peril, and I Know Who You Are and I Saw What You Did.

According to a 2015 survey by analytics company SAS, 64 percent of Canadian consumers are worried about how companies treat their personal data—and of that group, only 13 percent believe they have total control over how that information is used.

At first glance, Champoux may seem like a poster child for irresponsible online usage: a social-media addict who willingly, even enthusiastically, broadcasts detailed accounts of her most wrenching moments. But Champoux enjoys a lot more privacy than the over-caffeinated coverage about hacks and data breaches might suggest.

“I am meticulous in following certain rules,” she explains. “In general, my children are referred to by initials on Facebook—never their full names. If I post pictures, they are visible only to my friends—never public. And I always ask other parents’ permission if I post a picture of their own children.”

Champoux does not consider herself a reckless exhibitionist. When I press her about the sheer volume of content she posts, Champoux calls up the Facebook settings on her phone and shows me a long list of carefully curated distribution groups such as “Cancer” (only people who have suffered from it), “Work,” “French” (some francophones get offended by English posts, she explains), “Close Friends,” “B-List,” “D-List,” and the ultra-elite “VVIP,” which is limited to the eight most important people in her life. Every time she posts, Champoux says, she thinks carefully about precisely which audience she wants to target.

These enhanced privacy tools began emerging in the aftermath of Facebook’s final 2012 settlement with the US Federal Trade Commission addressing the above-described allegations. But the broad trend toward empowering consumers with fine-grained privacy control now can be observed throughout the software and social-networking world more generally. It’s a landmark development that has received far less attention than the moral panic that preceded it.

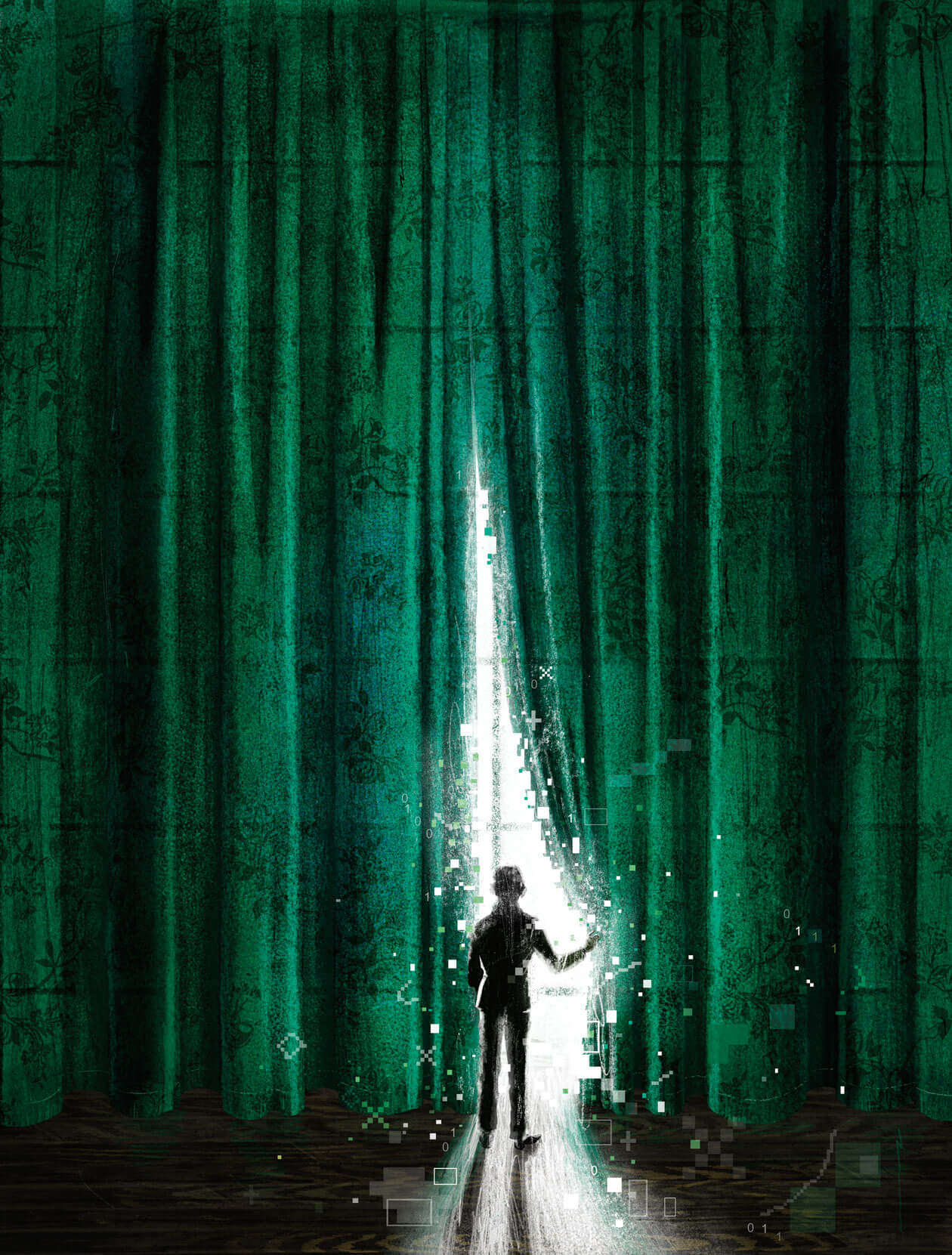

The most remarkable aspect of this privacy revolution is that it is being powered primarily not by new laws, but by corporations acting in their own economic self-interest. In time, it will completely reshape not only the way we interact with the digital world, but also the way we experience trust—and fear—in the post-9/11 capitalist security state.

Until now, the battle for privacy has been waged on two fronts. As Western governments massively expanded their oversight powers to counter the terrorist threat, civil libertarians correctly emphasized privacy as a shield against the state. But with the explosion of digital media and social networking, intrusive online corporate interests also became part of our collective neurosis. George Orwell taught us all to fear Big Brother. But in 2016, who is Big Brother? CSIS, which monitors our email messages without our consent? Or Facebook, to which we surrender our secrets willingly?

The answer, as I discovered, is that the corporate world has voluntarily renounced the role: big companies such as Google, Facebook, and Microsoft have learned the hard way that Big Brother is not a good look for anyone looking to build customer trust and make money.

“They’re actually really easy to use,” Champoux tells me when I confess that I’ve never taken the time to adjust the privacy settings on my own social-media posts. “People complain to me about how nothing is private and companies can spy on them. But in, like, four minutes, they could configure everything exactly the way they want. If that’s not something they’re willing to do, whose fault is that?”

The tension between privacy and technology was first described in definitive form on December 15, 1890, when future US Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis and his law partner Samuel Warren published a now-legendary Harvard Law Review article entitled “The Right to Privacy.” The two lawyers argued the then-novel proposition that the protection of privacy should no longer be treated as a mere offshoot of the law of libel, intellectual property, or contract. Rather, “the right to be let alone” should be regarded as a bedrock common-law principle. Sounding very much like twenty-first-century media critics lamenting the practices of TMZ, the authors cite a case in which a Broadway starlet was “surreptitiously” captured on film. “Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise,” they wrote, “have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life.” (According to one theory, the article was inspired by Warren’s furious response when his daughter’s high-society wedding became fodder for “yellow journalism.”) Revolutionary at the time, the idea that privacy should be written into the social contract is now an accepted principle in many parts of the developed world.

And yet, throughout much of the twentieth century, privacy never truly was embraced as a human right on par with racial and sexual equality, fair working conditions, and free speech. During the 1940s and ’50s, privacy fell prey to the human-rights apocalypse brought on by fascism and communism. The opening of mail, the bugging of phones, the practice of neighbour snitching on neighbour—all of these were standard practice in Nazi Germany and the USSR, both of which sought to destroy the very idea that an inner life could exist outside of state control. The terrifying union of industrial technology and totalitarian power lust—symbolized in literature by the telescreen of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four—ultimately inspired the inclusion of privacy protection in many of the international humanitarian covenants created after the Second World War.

Across the Western world, governments did pass privacy legislation—including here in Canada, where British Columbia created the country’s first privacy law in 1968, following a scandal involving electronic eavesdropping at a trade-union meeting. But for the most part, these were vaguely worded instruments, devoid of the broad moral sweep of, say, the Human Rights Act or its provincial equivalents. BC’s law, for instance, allowed civil suits in cases in which someone had “wilfully violat[ed] the privacy of another person.” But the reach of the law was vague. “Essentially, [the bill] means you have a right to be left alone,” said the BC attorney general. “But it is also worded in such a way as to leave the legal definition of privacy in a specific case to the discretion of the court.”

The privacy landscape began to change rapidly with the popularization of the World Wide Web in the mid-1990s. Web-browsing software such as Mosaic could display both images and text—thereby allowing users to buy and sell things over the Internet. At first, this new retail technology didn’t amount to much more than a high-tech version of phone-based catalogue shopping. But merchants soon realized that the web could be used to track customer behaviour and demographic characteristics at a level of detail that once had been impossible.

Many users came to shrug off this corporate eavesdropping as a fair trade-off for the massive benefits of an Internet-enabled life. But those who worried about what Brandeis and Warren called “the sacred precincts of private and domestic life” began looking to the law for protection.

Artin and Lucie Cavoukian moved to Toronto from Cairo in 1958, fleeing Egypt’s Nasser regime with eight suitcases, two mothers (both survivors of the Armenian Genocide), and three children. The eldest child, Onnig, would grow up to become the renowned portrait photographer known as Cavouk. Then came Raffi, the platinum-selling children’s entertainer. The baby of the family, Ann would become a well-known public figure herself. Chief of research services for Ontario’s attorney general during the 1980s, she eventually served three terms as Ontario’s information and privacy commissioner from 1997 to 2014. During that time, she bore witness to the whole arc of transformation in digital privacy.

Cavoukian’s introduction to the issue of data security came in 1987, when Ontario’s first information and privacy commissioner, Sidney B. Linden, recruited her as his director of compliance. “Privacy wasn’t a big deal back then,” she told me during an interview at Ryerson University, where she is now executive director of the Privacy and Big Data Institute. “Instead, the focus was on freedom of information—the idea that we needed to remove barriers. Since data mostly sat in isolated storage rooms, companies could rely on what we call ‘practical obscurity’ to safeguard privacy.” Data was private because it was really hard to find. To get customer information, you’d have to retrieve it from a filing cabinet or a disk drive. Then, in the 1990s, came the World Wide Web. And everything changed.

It wasn’t just that the volume of available data increased by orders of magnitude. It was that consumers now could actually see their privacy being threatened—through unwanted emails, reply-all glitches, covert screen grabs, viruses, scams, hacked passwords, and fake websites. Privacy, Cavoukian realized, was a growth industry.

In 2001, the federal government introduced the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (widely known as PIPEDA). Unlike earlier provincial laws that allowed citizens and companies to sue one another for vaguely defined privacy breaches, PIPEDA—which didn’t reach full strength until January 1, 2004—enumerated specific standards for the collection, storage, and use of personal data. For privacy lawyers, business boomed as companies across Canada rushed to update their technical data-handling protocols.

Yet the legislation did little to change the level of trust between customers and businesses. “Basically, the law said that companies had to do three things,” says Adam Kardash, widely regarded as one of Canada’s top legal experts in the privacy field. “They had to have someone they pointed to as a ‘chief privacy officer.’ They had to go out and get consent for collecting the information they had—which typically meant getting people to click on a massive ‘terms of use’ agreement that no one ever reads. And they had to post a privacy statement, which also was written by lawyers. The whole thing was treated as just another annoying step you had to do after you’d created a new product or business.”

During this period, Cavoukian used her pulpit as privacy commissioner to push a more holistic approach: privacy-law considerations, she argued, should be embedded at every stage in the creation of new products and services—a concept she popularized under the label “privacy by design,” or PbD.

Cavoukian wanted companies to understand that protecting customer privacy wasn’t just a cost of doing business—it was a key component of corporate strategy. Customers were less likely to patronize a company that abused their trust by spamming their email accounts with ads or selling their data to third parties, even if this was permitted under terms of use. Kardash was one of the few lawyers who grasped this from the start. “The new thing wasn’t all the buying and selling on the web,” says Kardash. “The new thing was all this information about customers and transactions. I started telling my colleagues and customers, ‘Data is the asset. It’s something we need to protect.’ That was fifteen years ago, and my whole career since has followed this principle.”

PbD is now the dominant approach at leading tech companies such as Microsoft, Google, and Facebook. And the principle is embedded in the latest, and most ambitious, iteration of the European Union’s omnibus privacy legislation—which in 2018 will affect any businesses, including Canadian ones, operating in Europe.

And so the real question isn’t whether the corporate world is taking privacy seriously. It is. The question is why users had to wait so long for this to happen. The first popular web browser came online in 1993. Cavoukian was presenting lectures about PbD at the annual conference of international data-protection experts as early as 2002. Yet until just a few years ago, there was no clearly established corporate benchmark for the ethical treatment of user data. Why did it take two decades for the world’s smartest engineers to embed privacy into our daily experiences with digital technology?

According to Colin McKay, Google Canada’s Ottawa-based head of public policy and government relations, the answer lies with the way modern devices evolved. Until recently, says McKay, downloading an app meant agreeing to all permission requests demanded by that app: you couldn’t pick and choose. So if you wanted a specific feature, such as a camera or a device tracker, you had to enable ten other functions, thus exposing yourself to unintended privacy threats. “It took a while before we realized that users needed more control.”

Instead of stuffing all of Google’s privacy information into one giant terms-of-use document, the new Marshmallow version of Google’s Android operating system presents privacy choices in plain-language snippets that clearly specify what apps will access what information. And permissions can be customized on the fly—you can enable geo-location for your maps program but turn it off for photo tagging.

Surveys suggest that users are taking advantage of these new features. According to the privacy commissioner of Canada, the proportion of mobile-device users who said they “adjust settings to limit information sharing” went from 53 percent to 72 percent between 2012 and 2014. During the same period, users who reported turning off a location-tracking feature went from 38 percent to 58 percent.

McKay tells me that these refinements aren’t required by PIPEDA, which was conceived under the old terms-of-use model. Google is implementing them because “putting users in control is the best way to ensure they trust us—which means they will feel comfortable using more of our services.”

He provides the example of how Gmail automatically puts flight information from Air Canada emails into your Google calendar. “When that first happens, a user may think, ‘Wow, the whole world knows I’m on that flight.’ But because Android offers transparency about how the information travels, it shows you that the only parties who actually know this information are you and Google.”

The vast bulk of information Google collects isn’t tagged to individual users, but is, according to McKay, “metadata” that is useful only when batched anonymously. One prominent example is the collection of geo-location information from mobile-phone users who are driving a car or biking. Google isn’t interested in any one user’s movements but in the sum of the information, which allows a map program to provide everyone with real-time traffic information.

Similarly, the metadata Google collects on our web-browsing habits turns out to be an excellent tool for filtering out spam sites: “When users land on a suspect URL—the kind that sets off a whole bunch of pop-up ads—one of the first things they do is instantly quit the browser. They just turn the program off to make all the pop-ups go away. The fact that they do that provides us with valuable information about that site, which in turn helps us deliver better searches—but it only works if people trust us to collect their metadata.” (Google uses similar methods to filter out email spam: if users invariably delete a certain kind of mass-circulated message instantly after opening it, the company’s algorithms will know to tag it as junk.)

In the Google business model that McKay describes, privacy controls emerge as a critical asset: without a baseline of trust, users won’t supply the real-time digital interactions that create targeted advertising opportunities.

“Let’s say you’re going to California,” McKay tells me. “And you’re using Google’s photo service to upload all your pictures. We see where you’re going, what hotels you’re staying at. And maybe next time you’re in this part of the world, our advertisers suggest other places to stay. That’s where we make our money. But it only works if you trust us when we tell you exactly what we’re going to do, and not do, with your data.”

On January 15, 2002, Bill Gates sent out a company-wide email identifying his “highest priority” for Microsoft’s then-new software support platform, known as .NET. “If we discover a risk that a feature could compromise someone’s privacy, that problem gets solved first. . . .These principles should apply at every stage of the development cycle of every kind of software we create, from operating systems and desktop applications to global web services.” Gates did not use the term “privacy by design.” But what he told Microsoft employees a full fourteen years ago—at a time before Facebook or Twitter existed—aligns with today’s state-of-the-art privacy practices.

The Microsoft executive charged with overseeing this area—chief privacy officer Brendon Lynch—joined the company in 2004. During an interview at the company’s global headquarters in Redmond, Washington, he told me that the last twelve years have seen a significant shift in the way privacy is discussed within the firm and, more broadly, across the industry.

“It used to be that the word ‘privacy’ meant things like secrecy, the right to be left alone, the right to keep junk out of your inbox,” he says. “But it’s much broader than that now. What people really seek—I use the word control. That means giving people more tools to define the exact level of privacy they want.”

By way of example, he cites Microsoft’s Cortana software, a personal assistant that, over time, teaches itself about a user’s specific patterns. “To make sure the user is totally comfortable, the software will ask questions like ‘Would you like me to track your flights?’ And whenever you’re not quite sure about how Cortana knows something about you, you can click the link that says ‘How did I know that?’”

The example of Cortana helps illustrate the quantum leap in tech sophistication on the privacy file over the last twenty years. When I raise the question of whether even a single Microsoft engineer was assigned to privacy issues on the company’s legendary MS-DOS operating system back in the 1980s, Lynch tells me that he isn’t sure whether there was anyone with that mandate. In that era, it’s likely that “privacy” meant keeping your floppy disks in a locked filing cabinet.

Or consider the complex privacy conundrum Microsoft faced when it introduced the facial-recognition features embedded in its Kinect motion-sensing input system for Xbox. “The technology required us to record a 3-D image of a user’s face,” Lynch says. “The question then was, what do we do with that information? Since regulators had never dealt with this situation, we had to answer it ourselves.”

Microsoft’s solution: store the recorded image data as a series of decontextualized geometric data points, avoiding any sort of recognizable graphics image, and ensure the data never leaves the confines of the physical Xbox itself, even when the gaming unit is connected to the Internet.

Privacy advocates often focus on what kind of laws are required to police the way our data is collected and used by corporate actors. But as the examples of Cortana and Kinect show, digital technology moves too fast for lawmakers. In effect, governments have no choice but to rely on profit-motivated self-regulation by the likes of Brendon Lynch and the engineers who consult with his team.

What will be the biggest privacy challenge in coming decades? According to Lynch, the Internet of Things. By which he means the appropriate use of data generated by network-enabled vehicles, appliances, wearable gear, and personal gadgets. Should your TV be ratting out kids for watching X-rated shows? If your recycling container senses the wrong kind of refuse, should it tell the sanitation truck to skip your house? If your fridge knows that you had half a bottle of white wine, should it tell your car? And, if so, should your car tell other cars—including, say, the ones marked “Police”?

These issues seem ominous. But it should be a source of reassurance that today’s operating systems are typically far more secure than their predecessors—in large part because engineers have designed them from the ground up in a way that reflects PbD principles.

This includes Android, the most popular mobile operating system on the planet. In creating the privacy environment for Android’s latest iterations, Google wanted to steer clear of the old Windows-style desktop model, whereby both the operating system and any installed security software would act as all-seeing overlords, monitoring every other piece of software. “Under that model, the software installs a kernel driver that provides universal access,” says Android security chief Adrian Ludwig. “With, say, Windows, the OS sees everything. But it’s also responsible for everything and has the ability to affect everything. There are big risks with that.”

Android relies on a completely different approach, based on a concept called “application sandboxing.” In the sandbox model, when a user interacts with an app, the operating system fades entirely into the background. “Let’s say you have Skype installed on your phone,” Ludwig says. “Not only does the Android OS not want to listen in on your call—it can’t listen in on your call. We’ve specifically designed it so that this power just doesn’t exist.”

The result, says Ludwig, is that the Android OS installed on smartphones simply can’t be hijacked by a third party. “With the Chrome web browser, we typically get malware rates of 10 to 15 percent on a desktop install. On mobile, it’s less than 0.5 percent.”

Ludwig, a trained cryptographer, is proud of his work at Android and of Google’s work in the privacy space more generally. But when I ask him about privacy controversies that have affected other tech giants, including Facebook, he’s careful not to crow.

“I’m actually very sympathetic to a lot of the issues that social-media companies have dealt with,” he says. “What Google is really about is the way one person shares information with one company, Google. But social media is different. When you put something on Facebook, you’re sharing it with a thousand people. Or with the whole world. Stuff gets screengrabbed and sent around the Internet. And what you think you want to share today, you may not want to share tomorrow. How do you create privacy policies for all that? It’s way more complicated.”

Facebook’s campus in Menlo Park—just three Caltrain stops north of Google, on the way to San Francisco—is divided roughly into two sections. There’s the part with dozens of small, brightly coloured office buildings, cafés, and shops, creating the impression of the student centre at a big university. And there’s the part consisting of a massive Frank Gehry-designed building known as MPK 20. All of the 2,800 workers at MPK 20 are contained in a single open-concept 430,000-square-foot chamber covered with a garden roof—a haven for local and migratory birds and home to an outdoor restaurant serving high-end grilled cheese sandwiches.

Consistent with the quirky atmosphere one expects in Silicon Valley, the names of MPK 20 meeting areas are little fragments of cleverness, including “Double Negative” and “The Misuse of Your/You’re.” There’s also a large one named Ada Lovelace—after the nineteenth-century English countess and mathematician whose work on algorithms arguably qualifies her as history’s first computer programmer. That’s where I watched Mark Pike, Facebook’s privacy program manager, train the company’s new product managers.

“The basic principle you have to remember is the ‘audience rule,’” Pike says. (“Audience” means the set of people who can see any given post.) “We won’t ever change someone’s default audience without having them click a button.” This statement addresses one of the reasons the FTC first got involved in 2011. It’s a reminder of the rule Facebook now always comes back to: tell its 1.5 billion active monthly users exactly what’s being done with their data and then stick to that.

Facebook is betting that investing in privacy-on-demand protocols will incentivize deeper engagement with its product—an essential gamble given the company’s ambition to have users carry out most of their interactions and transactions exclusively on its platform (one reason the social network is the busiest on the planet—with more than 250 million posts per hour—is that it now offers a news feed, a Messenger chat app, a photo-sharing feature, and a video-player feature, as well as popular applications such as Instagram, WhatsApp, and Oculus VR).

Facebook’s interest in being an Internet-unto-itself has made it alert to the fact that different users have different privacy needs. Not all of us are like Champoux. Some prefer to tell the world less, or nothing at all. Under Silicon Valley’s new paradigm, privacy has become a matter of personal choice.

As with Google’s Android operating system, Facebook’s privacy policy is governed by granularity. While the company once provided users with only a few very basic privacy options, the audience-selection process now is completely à la carte: not only can users create reusable distribution lists of the type Champoux showed me, they can also micro-tailor individual posts to a customized group of recipients—such as, say, a Donald Trump–bashing post that you might want to make available to everyone on your friends list except for a certain right-wing brother-in-law. (The “custom privacy” pop-up window allows users to manicure distribution on either an opt-in or opt-out basis, presenting both “share with” and “don’t share with” input windows.)

“It’s important to avoid any kind of nasty surprise,” says Inbal Cohen, Facebook’s product manager for privacy. “Sometimes, a user will set the default audience to ‘public’—which may be fine for one post, but a horrible mistake for the next one. That’s why we now have a pop-up window that reminds people—at the moment they’re about to publish their post—exactly who is going to see it. The bottom line is that if Facebook is a bad experience for a user, it’s a bad experience for us.”

While pop culture continues to push the narrative that privacy is disappearing, the reality is very much the opposite: privacy protection has become a huge element of both engineering design and corporate branding in the technology industry. Just two decades ago, the International Association of Privacy Professionals could expect a few dozen people at its international meetings. At its 2016 Global Privacy Summit in Washington, DC, there were more than 3,500.

But, of course, no technology can totally safeguard our privacy. In the real world, we lose passwords, leave computers unattended, click on phishing scams, share log-in information with friends who turn into spiteful ex-friends. In the real world, there is an Ashley Madison for every Google. As I write this, journalists around the world are sifting through 11.5 million leaked documents describing shell companies and offshore accounts connected to the Panamian law firm Mossack Fonseca. It didn’t matter what software or social-media controls the firm’s clients used: their privacy was entirely out of their control.

Toronto-based private investigator Mitchell Dubros does not look like all those brilliant, fresh-scrubbed, impossibly young things I interviewed in California. He’s my age—in his late forties—with hair combed to the sides and back like Willem Dafoe in To Live and Die in L.A. And when he talks about what he does for a living, he projects the sort of hard-bitten cynicism that film noir has taught me to expect.

“Yes, the digital revolution has affected my job and the industry,” he tells me over coffee. “But it’s still all about human beings and where they live and work. Cheating on your partner is an easy thing to investigate—because there’s a physical aspect to it, which is why investigators spend a lot of their time doing old-fashioned stuff like staking out someone’s home. In most cases, all I need is some basic information such as your cell number. If I want to know where you’re working, I can just call it and say, ‘Hi, I’m calling from ABC Couriers with a package for you, but the address is smudged out.’ It’s easy.”

Dubros tells me that a private investigator sometimes has the ability to track cellphones. “In the old days, it was easier. The phone-company oligopoly meant you only needed one or two people on the inside to get access to subscriber information,” he says. “Deregulation has made it harder, because now you need someone at a dozen different companies. But it’s still doable.”

All this has made Dubros fatalistic about privacy. “After thirty years in this business, I’ve learned that if someone really wants to know something about me, they will find out,” he says. “I’ve come to terms with that fact, I guess. The advice I give to people who are worried about privacy is simple: keep your nose clean.”

Champoux returned to social media after her husband’s shiva, and has spent the last few months posting under the #Widowhood hashtag while uploading a stream of family photos that “document our first year as a team of three.” Facebook, she told me, had helped her stay socially connected during a time of grief.

In an interesting development, about seven days after her husband died and she changed her relationship status to “widow,” Facebook started to suggest she become friends with single men over forty. That seemed unsettling to me. But Champoux wasn’t fazed. “It’s just an algorithm,” she says. “No one is invading my privacy.”

But in other areas of online life, the algorithms aren’t always quite so innocuous. While privacy standards are being strengthened at leading Internet companies, there is no similar trend afoot in the area of government security surveillance. When it comes to protecting airports, keeping ISIS terrorists from getting into our country, and disrupting plots, there are no pop-up menus and privacy controls. Indeed, the whole idea of security-focused surveillance is to remove our control. In Canada, privacy advocates have been worried about the RCMP’s alleged use of invasive technologies called “stingrays,” which mimic cellphone towers and harvest identifying data from nearby mobile phones. Increasingly, even businesses are being forced to submit to inspection whenever there is prima facie evidence of criminal activity. When the FBI cracked the iPhone of San Bernardino killer Syed Farook, they didn’t check to ensure that this was consistent with Apple’s terms of use. They just did it. And they will continue to do it. Because in this age of terrorism, the tension between privacy and security always will be resolved in favour of the latter.

But it’s also important to recall how strenuously Apple fought the government’s demands that it open Farook’s iPhone, arguing, according to court records, that being forced to do so “could threaten the trust between Apple and its customers and substantially tarnish the Apple brand.” So while Western society is not about to enter a golden era of perfect digital privacy, it’s increasingly clear that the most serious privacy threats to the average citizen will come from one direction only: the surveillance state.

When leading technology companies began implementing the privacy-by-design paradigm, they weren’t setting out to transform the mix of fear and trust that guides our attitudes toward public and private institutions in our society. Yet that’s exactly what they’re accomplishing. In this new world, Virginia Champoux will have much to fear from the surveillance state. From Mark Zuckerberg: not so much.

This appeared in the June 2016 issue.