The feeling from that ominous Friday morning still stands out in his memory twenty years later. As James Murdoch grabbed a handful of beta tapes and the sequence list to start editing the weekend edition of Canada AM, the seasoned producer was interrupted by his ringing telephone. A secretary was on the line, asking thirty-seven-year-old Murdoch to meet the vice-president of CTV in his office immediately.

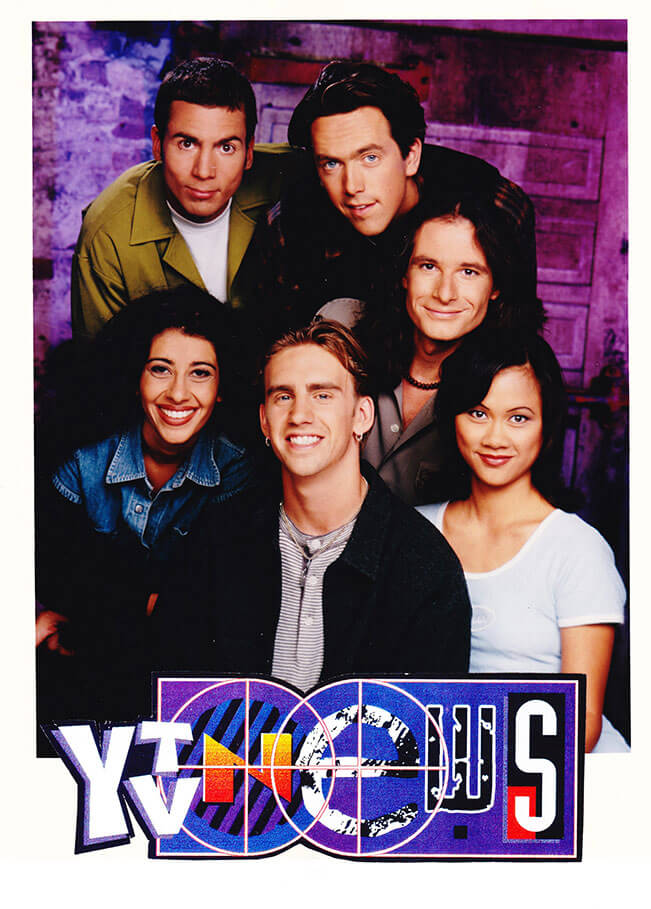

The network had recently partnered with YTV Canada to develop YTV News, a half-hour weekly news program for children. The television newscast covered domestic and international news items of interest to viewers aged seven to twelve. First airing in 1993, YTV News was then in its second twenty-six-episode season.

“When the vice-president said ‘Look, I need you to come in and pick up the rest of this season and pick up the next season,’ I thought it was a demotion,” says Murdoch. “I thought I was being kicked in the head.”

Murdoch was pulled from Canada AM Weekend and assigned to start work as producer of YTV News. His new task would be to boil down the news of the week for the child audience. Using the studio, crew, archive, and feed material provided by CTV News, the show aimed to make the world explicable to children.

Some of the week’s top stories were presented on the newscast from Toronto. Six twenty-somethings took to the screen for the Sunday afternoon show to report on the latest trends, politics, school life, transportation, music, and other topics of interest.

Critically, the program was well received. The show won a New York Festivals award for Best Youth Information Series and two Canadian Television Program Festival awards. Two of the most recognized episodes included an on-location special about the conflict in Northern Ireland and a broadcast out of Montreal during the 1995 Quebec Referendum.

“We did strive to look at issues and to explain issues without pandering, without talking down to anybody,” says Murdoch.

Cynthia Carter has studied the relationship between children and the news since 2002. The senior lecturer at Cardiff University believes that news programs provide children with opportunities to share their ideas, thoughts and feelings about the world around them. “You’re engaging children in the conversation about issues and debates and society and helping them to develop as citizens,” says Carter. “So that one day when they are adults, they’ll take an active interest in and participate in social and political life.”

With today’s around-the-clock coverage of the Syrian refugee crisis and frequent natural disasters, for example, it’s hard for children not to pick up on the happenings of the world. Carter emphasizes the importance of having a news source dedicated to putting stories in perspective and making them clearly understandable for kids.

Her research points out that without a foundation in current events from a young age, children are reluctant to participate in the public sphere as they get older—the wimpy 38.8 percent voter turnout among eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds in the 2011 Canadian federal election attests to this idea. Carter also found that adult news does not provide enough context for the child audience. She says six- to twelve-year-olds “want to know what’s going on and they want it from a children’s point of view.”

YTV News aired its final episode in 1999, turning off the last Canadian national news program aimed at children. “I think they just looked at the numbers, looked at the money they were spending and thought ‘we can put our resources somewhere else,’” says Murdoch. “Like everything, it just changes after four or five years of doing it.”

The show’s cancellation has created the longest gap in Canadian TV history without news programming for children.

Each weekday morning Anne-Marie Smyth drives her car through Dublin to work at Radio Television Ireland, known locally as Raidió Teilifís Éireanne or RTE. As editor of news2day, a daily eight-minute newscast for Irish children aged seven to twelve, it’s her job to sift through the news of the day and decide what will air on the children’s program.

Smyth works in the main newsroom at RTE. Her desk is positioned right behind the anchor and presenter of Six One, the national evening news for adults. Sitting to the right of Smyth are the business reporters, the industry and employment reporters, and the business editor, all tapping away at their keyboards. Hurried conversation, flipping pages, and vibrating smartphones fill the biggest newsroom in Ireland.

When news2day goes to air at 4:25 p.m. on RTE Two, the newscast plays before the eyes of roughly 30,000 children—scheduled during after school programming to catch children between their favourite shows.

News2day gets its main viewership when streamed online through the RTE Player online portal. The program is among the twenty most-watched items on the site. Smyth says the newscast gets most of its exposure through schools, when teachers show it at the start of class. RTE estimates that news2day reaches an extra 60,000 children through classrooms. But the Irish show is not the only European children’s news program. Europe is home to eleven national newscasts for kids. Like news2day, each one is produced by a public broadcaster with a mission to provide news and currents affairs to people of all ages and levels of knowledge.

“More than ever now,” says Smyth. “I think it’s important to have something which is a trustworthy and reliable outlet for news for them, which doesn’t have a bias or an agenda, but is a very neutral and well explained version of what’s going on in the world.”

News stories for children are told in a different way than those for adults. Making sure that the content engages the target audience and does not frighten viewers is part of the thinking that goes into making news for kids. On any given day, Smyth might pick up the phone and contact one of her ten European counterparts to find out how they’re planning to cover a story.

“There could be something that may be shocking or scary,” says Smyth. “For example, a shooting in a school in the US. We would still cover that.”

Graphic language that can sensationalize adult news stories is removed for the child viewer, and reporters for news2day use careful, neutral language to tell the facts. Smyth says most often the story will focus on the positive action coming out of the event, to give the child a sense of reassurance.

“We might try and start it with ‘President Obama has called for tougher gun laws after another incident,’ ” says Smyth. Highlighting the call for justice gives younger audiences “depth and understanding” without the worry. Many studies have found that mainstream media coverage of tragedies like war, conflict, child abduction, and murder are emotionally distressing for children.

“Growing Up With the News,” a study conducted in 2007 by the Pew Research Center in Washington, DC, found that American parents often shield young children from international and domestic news coverage. The study concluded that nearly one in three parents with children under the age of six protect their kids from the news. This compares with 27 percent of parents with children aged six to eleven and 14 percent of parents with kids aged twelve to seventeen.

MediaSmarts (formerly known as the Media Awareness Network) is an Ottawa-based non-profit that analyzes mass media and promotes critical thinking skills for young audiences. Thierry Plante, a Media Education Specialist at the organization, says that children who challenge the information presented on TV are more protected from harmful media effects like anxiety or the influence of advertising.

He emphasizes that parents who watch television with their children increase media benefits by adding context to what happens on screen. Using what’s on TV to start a conversation with children gives them an opportunity to ask questions. “Any kind of educational effect would be maximized.”

Change the channel as much as you like and you’re still not going to find a children’s newscast on Canadian television. Scott Hutton, executive director of broadcasting at the CRTC, says there are “no provisions made for children’s broadcast news in Canada.”

“Quite frankly, the issue of news for children has not been raised or brought to the forefront,” says Hutton.

There isn’t much financial incentive for broadcasters to produce newscasts for children, says Doug Barnes. The former executive of production for children’s television at the CBC knows that making news programs—whether for children or adults—isn’t cheap. Compared to drama or cartoons, news is more expensive to produce. Advertising restrictions on kids programs in Canada also put pressure on a network’s bottom line. According to the Broadcast Code for Advertising to Children, “no station or network may carry more than four minutes of commercial messages in any one half-hour of children’s programming.”

Barnes says the CBC’s program menu for children has “changed drastically” since his departure in 1998 due to budget cutbacks to the publicly funded corporation. He says the main issue today has “less to do with a news show” than with the network’s decision not to produce any TV programs for children at all. Instead, the CBC buys kids programming from countries such as the US, the UK, and Australia. “That model is financially much more viable for them,” says Barnes. “It’s about finance more than anything else.”

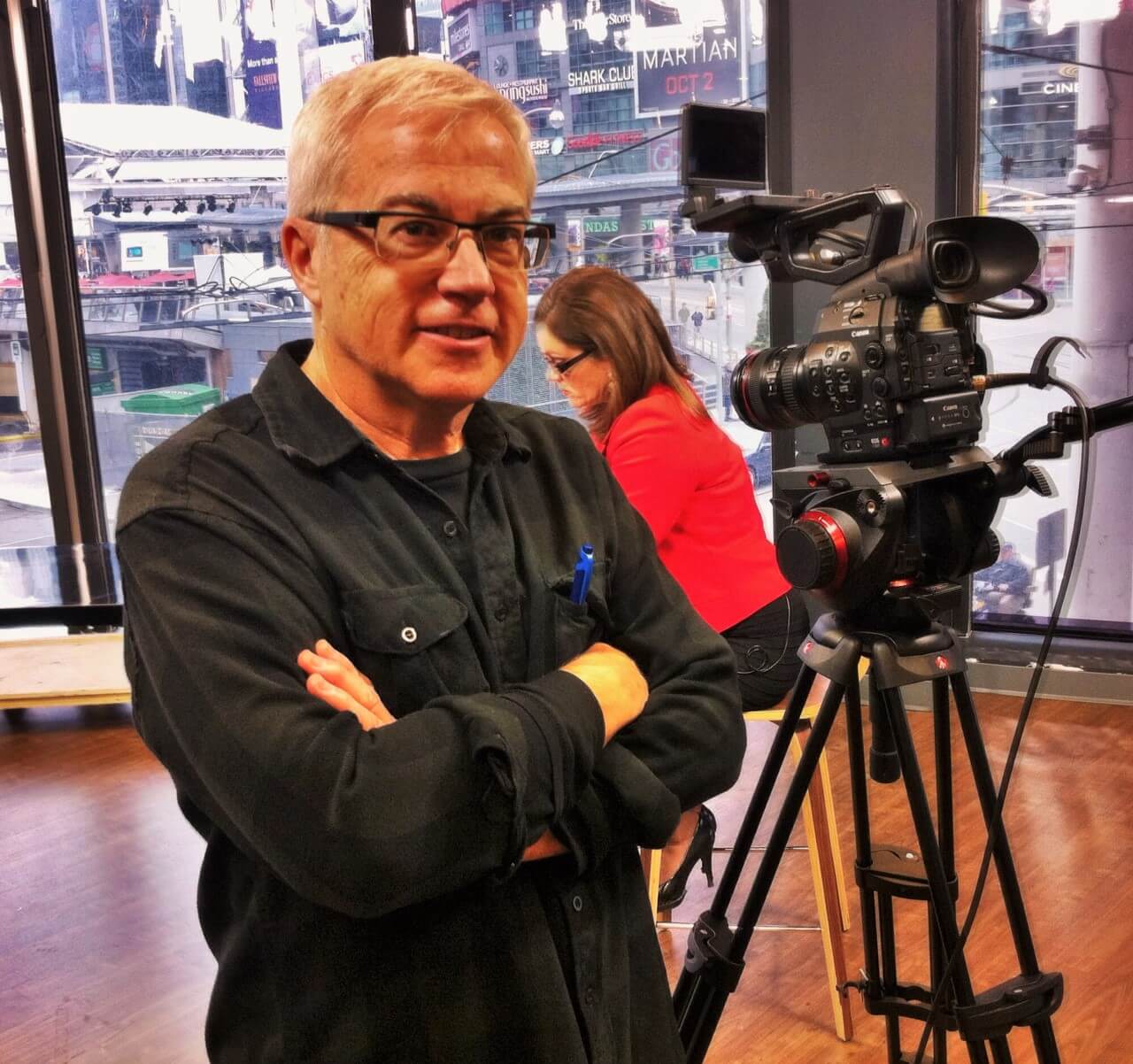

Classical music plays from inside Murdoch’s editing suite in Mississauga. We’re listening to the intricate melodies of five German composers. The robust sounds of brass instruments clash against the backdrop of family photos and career memorabilia that decorate Murdoch’s workspace.

Although not a classical music fan, the silver-haired husband and father of two daughters comfortably blends audio with visual for a documentary titled Exit Music for the Royal Conservatory of Music. Constantly adding projects to his beefy resumé, fifty-eight-year-old Murdoch fondly reflects on his six years spent producing news for children.

“Within the first two weeks I thought ‘This is amazing,’ ” he says. “It was such a challenge, it was such an eye-opener. It gave me a broader scope of being able to hit that market and have fun. And boy, did we have fun.”

Murdoch wonders whether “this kind of niche television has a place any more” in the child market. When he was producing YTV News, the Internet was in its development stage and mobile phones still had long external antennas. Technological advancements have propelled news outlets to change the way information is delivered and received.

A 2014 survey conducted by the CRTC on media habits of young Canadians found that 37 percent of kids aged nine to twelve use their smartphone every day. Tweets about breaking news, snaps of raw footage, and posts about news articles on social media sites are how today’s children get their information—all in the palm of their hand.

Despite the wide array of media platforms, Murdoch believes that children need a news source of their own. Specifically, something that will “spark discussion” and tap into their willingness to take an active role in society. “I feel that so many young people today just do not have any grounding at all in current affairs,” says Murdoch. “It’s quite sad.”