Perhaps still feeling a bit chilled by the arena air, former Manitoba curling great Bob Boughey brought out what he likes to call his Holy Grail, a curling broom with a hollow handle filled with Southern Comfort. “It’s an all-purpose vehicle,” hooted Boughey, a broad-shouldered former rugby player, as he uncorked his broom and took a swallow of bourbon. This is the Snake Pit at the venerable Fort Rouge Curling Club in Winnipeg, the backroom where in stricter times select members could bring their own alcohol while the rest of the club was dry. Today, those bastions of fading testosterone are filled with collegial humour, where skips who have won their share of trophies congregate to drink beer or whiskey on the rocks, but never a gin and tonic. Usually well over fifty, and wearing faded flannel shirts and ball caps, they razz each other endlessly, tell bad jokes, and laugh on cue as old stories are repeated yet again.

Like the sport itself, the Snake Pit lacks pretense. The floor is covered in faded linoleum and decorated with a few wooden tables that overflow with plates of mayo, sliced turkey, and potato chips. It would have been bad curling etiquette to turn Boughey down in this atmosphere, so I tilted my head back and took a swig as the guys roared, but being a wine writer from Napa, California, I can translate the subtleties of a new vintage of Pinot Noir more easily than I can describe the warm, sweet contents of his broom.

But in a way, that’s exactly why I’ve come to Winnipeg: I want to know what it is about the ancient game of curling that brings nearly 1.3 million Canadians out to more than 1,200 chilly rinks each year. Sure, elite curlers will soon be competing for spots on Canada’s Olympic team; weekend players will settle in for a game and a drink; and the thousands of fans who revolted over the cbc’s erratic television coverage of the Brier last year will rejoice over the fact that another broadcaster, with anchors no doubt dressed in tuxedos, may be handling the championships this season. But it is the mystic nature of the sport that intrigues me. Who can say when man first slid a stone across a frozen river? And weren’t the first rules of curling laid down in Latin by Scottish scholars centuries ago?

Winnipeg is the bull’s eye, or button, as it were, of the game in Canada. So what better place to start my journey into the sport that was once known as growling, after the sound a rough stone makes as it moves across the ice. There was no shortage of games to watch at the Manitoba Curling Association Men’s Bonspiel, the largest gathering of curlers in the world. The matches were staged at rinks in and around the city, and the 2005 event had 467 teams, nearly 2,000 curlers. Participants ranged from eighteen through eighty, a reflection of the fact that the Manitoba Curling Association’s motto is, “Curling is a lifetime sport.” Of course, the association’s unofficial motto for mca is “Must Consume Alcohol”—an apt slogan that echoes back almost 500 years to games that were played in Scotland with the winners enjoying a free round of grog.

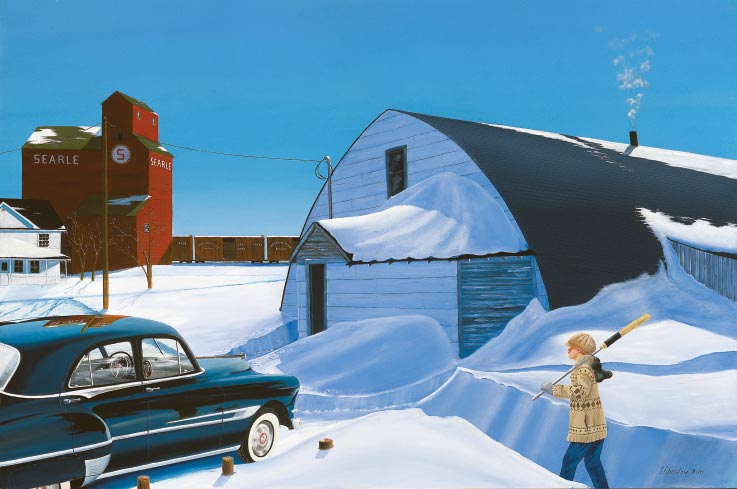

I have skied numerous times and have spent some very cold days and nights while travelling in Quebec, but when I flew into Winnipeg last wintery my face and body were still surprised by the ferocity of the cold. After a couple of minutes outside, I could feel a small frozen morsel of ice, something that began as a bodily fluid, collecting around my nose and mouth. I had never tasted air so cold, and imagined that if I screamed it would, cartoon-like, freeze a few feet from my face, drop, and crack onto the snowy sidewalk.

Knowing nothing about the game, I immediately tracked down local curling legend Don Finkbeiner, fifty-nine, who volunteered to be my guide. Everybody in Winnipeg seemed to know Finkbeiner, resplendent with cropped, silvery white hair. In 1976, he was on the Manitoba men’s championship team and went on to represent the province in the Brier. In fact, I saw his 1976 trophy, slightly dusty, sitting with other sports relics from the past inside the Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame, which is located behind the clearance department on the fifth floor of a Hudson’s Bay Company department store.

Over a tasty bison tenderloin and a glass of 2001 Osoyoos Larose, a lovely BC Bordeaux-styled blend, at the Fusion Grill, a trendy little restaurant, Finkbeiner patiently tried to explain the game to me, a task complicated by the fact that the rule book is twenty-one pages long. The more he talked the more his eyes lit up, and a smile poked across his lips. “The skip builds the games and directs the traffic,” he said, hoping I was finally catching on. “He’s really like a chess master.”

The more I studied the games over the following days, the more I realized that Finkbeiner was right; in many ways comparing curling to chess was an apt analogy. To win, a player has to slide at least one of eight stones his team controls closer to the button than his rivals. On first blush that seems simple enough, but like chess it requires thinking several moves ahead, strategically placing the rocks to set up the final, and usually winning shot. On the Canadian Curling Association website, the strategy surrounding a system known as the Four-Rock Free Guard Defence covers forty-two pages, replete with carefully detailed diagrams. The site also contains a glossary of eighty-eight often mysterious-sounding terms, such as dead handle (a rock that fails to spin), heart (the crest given to a provincial champion), and wick (a glancing blow intended to move a stone sideways). And it doesn’t include many centuries-old terms that have long since been dropped from usage.

After Finkbeiner’s convivial tutorial, I headed to the Pembina Curling Club to witness curling theory sliding down the ice into practice. The size of an airplane hangar, and just a few degrees above freezing, the club was chosen to host the opening ceremonies. A group of about sixty that included tournament officials, past champions, players, local press, and politicians mulled about in the cold. Bagpipes usually don’t get me excited, but I broke out in goosebumps when the Khartum Shrine Temple Pipe and Drum Band, dressed in appropriate Scottish attire, began playing their goat-skinned hearts out. It was as if the Queen herself were about to step out and attempt a stone-cold draw to the button.

A series of speakers (mostly politicians) marched onto a red carpet held down with curling rocks, came up to a lectern, and spoke elaborately about the past glories of the sport. “The popularity of curling itself in Manitoba tells you something about this province,” said Manitoba Lieutenant Governor John Harvard. Then, after a solemn drum roll, and of course a “wee bit of a drink” (a recurring theme), Manitoba curling legend Bill Howie, dressed in the requisite kilt, expertly threw out the first rock, which glided silently down the ice to the button. Participants stretched their backs and hamstrings, and rolled their shoulders. Some wandered around, others drank a few beers. Shouts of “Sweep, Sweeeep!” and “Hurry, Haaaarrd!” soon echoed through the rink, lending a sense of urgency to a sport in which participants seem to spend a good deal of time leaning on their brooms talking strategy.

Curlers have been striking that reflective pose since at least the 1500s in Scotland, where the game is believed to have originated. One of the earliest matches involved two Scottish monks, John Sclater and Gavin Hamilton, who, according to accounts published in Latin in 1540, “would go to the ice at an appointed place and they would there have a contest with stones thrown over the ice.” The game flourished, in part because the Scottish Parliament had recently banned football, claiming it would lead to hooliganism. (They were right.) By 1773, curling had become so established that Scottish poet James Graeme was moved to describe the game:

The goals are marked out;

the centre each

Of a large random circle;

distance scores

Are drawn between,

the dread of weakly arms

Firm on his cramp-bits stands

the steady youth

Who leads the game:

low o’er the weighty stone

He bends incumbent,

and with nicest eye

Surveys the further goal,

and in his mind

Measures the distance;

careful to bestow

Just force enough;

then, balanc’d in his hand

he flings it on direct; it glides along

Hoarse murmuring,

while, plying hard before,

Full many a besom

sweeps away the snow

Or icicle, that might

obstruct its course

At about the same time Graeme was writing his poem, Scottish troops stationed in Nova Scotia fought off boredom by melting down cannonballs to fashion curling irons (stones). The first club in Canada was established a few decades later in Montreal, by twenty merchants who had been playing on the frozen St. Lawrence River.

This all adds up to a rich history (you can almost taste it in Winnipeg), but after taking in dozens of games I have concluded that it will never be among the sexiest of sports. There will probably never be a Sports Illustrated Women of Curling issue. It does not rank with auto racing, fencing, bullfighting, cliff diving, or even basketball for grace and aplomb. There is little action, and what there is takes place slowly. Yet the sport is heavy with drama and suspense, and incorporates aspects from other competitions: the strategic planning of chess, the controlled languidness of baseball, the physics-in-action precision of billiards, the back-and-forth of tennis, the self-regulation of golf, and the beer-drinking camaraderie of bowling.

The close bond that many curlers share is reflected in the good-natured banter at the Pembina Club, where Wendy Foster munched on cold pizza and watched her son, Jamie, play. “My son entered the bonspiel late, and he’s in a tough draw,” she explained between bites. Jamie’s team was up against it, battling 2002 World Junior Champion and tournament favourite David Hamblin. Hamblin was among the few pros competing, and prior to the match he’d focused by staring into space. Like his teammates, he was fit, toned, and ready to conquer. “We go into every event expecting to win,” said Hamblin, without smiling. He draws a comparison to golf. “Only you decide,” he said, “when to begin your swing.”

Hamblin’s team easily trounced Foster’s squad 12-2. Still, the fact that amateurs and club players can play against established pros is one of the unique elements embodied in the bonspiel. And sometimes, with a little luck, the amateurs even win. “Curling is a humbling game,” Finkbeiner had told me. “You can be so much better than the opposition and still lose.”

It does have a social hierarchy, though Often the name of the most pretentious curling club in a community contains the word “granite.” In Winnipeg, the “mother club” is the Granite Curling Club, which was founded in 1880. I didn’t find any curling brooms disguised as flasks there; it bore more resemblance to the Augusta National Golf Club, home of the Masters golf tournament, complete with stuffy men stuffed into stuffy blazers—except they were drinking beer instead of bourbon.

Clare Miller, a former Manitoba Masters provincial champion, has been a member of the Granite for forty-five years, and in our conversation he raised an interesting point. In a year when Canadians watched owners and striking players battle over $2 billion in nhl hockey revenues, and while nearly every professional sport has been damaged by the excesses of huge contracts and drug abuse, curling remained untainted. Sure, the purses for the big events have gone up, with teams competing for prizes as large as $150,000 on the World Curling Tour, but the game remains largely unchanged by either technology (a broom is still basically a broom) or temperament (as far as I could tell, there are no Todd Bertuzzis terrorizing the rinks). “I know of no other sport,” said Miller, “where all the competitors play the game in the positive sense, and do nothing detrimental to the game.”

The mca Men’s Bonspiel was a marathon. For match winners, it seemed to go on and on, and luck—in the form of a barely touched rock, a foul, or a disputed call causing a team to forfeit an end—could easily have determined a champion. Even Hamblin’s team got knocked out of the running. But his loss barely made a ripple in the Snake Pit, where Boughey’s uncorked broom was being passed around. “Curling offers a great combination of respect and no respect at the same time,” explained Neil Gottfred, as he listened to Boughey recite yet another story. Gottfred may have summed up curling better than anyone I met. It is a sport about participation first—in the end no one really seems to care which side of the score they come out on.