It was 4:35 a.m. on January 12, 2004, four below zero, with blowing snow and treacherous roads, when the twelve members of the Ontario Provincial Police’s Barrie Tactical and Rescue Unit (TRU) set off in two unmarked Suburbans, two gun trucks, a bomb truck, and an unmarked van. It took six hours to get from Barrie to the Chippewa of the Thames reserve, thirty kilometres southwest of London. When not spelling off the driver, Ron Heinemann positioned himself over the axle in the bomb truck’s windowless cube van, cleaned his weapons, put on his hostage rescue kit, and prepared charges for explosive forced entries.

With the truck’s non-existent suspension, twice when it hit bumps, Heinemann’s handiwork threatened to obliterate his crew. Heinemann wasn’t new to the game. He’d been on the Barrie TRU for almost a decade, was acting head of bomb tech for the province, and, as the most senior constable on the Barrie team, sometimes led training and field ops.

When they arrived on the scene, TRU members would go immediately to the front line, but, as in all such deployments, a senior officer known as the Incident Commander (IC), holed up in a command centre away from the action, would call the shots. Particularly since the Ipperwash Provincial Park occupation in 1995, when native protester Dudley George was shot and killed by Heinemann’s teammate Ken Deane, ICs had become increasingly gun-shy, ignoring crucial TRU Standard Operating Procedures (sops) that senior command thought too provocative for reserves.

The OPP does not generally have jurisdiction on First Nations land and must usually be invited to an incident by a chief or band council. But the Barrie TRU had been receiving more calls than usual in recent months, and one thing was clear: they were not welcome there.

Heinemann had been thinking about his recent sergeant’s exam and the course textbook, Harvard Business Review on Culture and Change. While most police forces followed the more prosaic program set out by the Ontario Police College near Aylmer, the OPP fancied itself a cut above and conceived its own exam. Half of the 100 multiple-choice questions were based on Culture and Change’s eight chapters, one of which had caught Heinemann’s attention.

“The Nut Island Effect: When Good Teams Go Wrong” is about a team of some eighty people who operated the Nut Island sewage treatment plant in Quincy, Massachusetts, from the late 1960s until the plant was decommissioned in 1997. Like a TRU, the Nut Island team was dedicated, innovative, and self-governing. They had esprit de corps, watched each other’s backs, and even dug into their own pockets for spare parts and other necessities. There was one problem: their dedication and self-sufficiency set the stage for catastrophic failure. During a six-month period in 1982, this competent and experienced staff released 3.4 billion tonnes of raw sewage into Boston Harbor.

The study describes the psychopathology that afflicts organizations when communication between managers and the managed breaks down. As the chapter describes, in most cases, the Nut Island Effect “features a similar set of antagonists—a dedicated, cohesive team and distracted senior managers—whose conflict follows a predictable behavioral pattern.” The team develops an outsider mentality, both heroic and isolated. Eventually, communications become so strained that the workers feel taken for granted, and both sides lose focus on the job at hand. Senior management turns a blind eye to operational dysfunction until catastrophe hits. At that point someone becomes the fall guy and all bets are off.

This resonated with Heinemann because it seemed to map his and other officers’ experience with the OPP since Ipperwash: eight years later, the force was definitely in the throes of the Nut Island Effect.

The OPP formed its first TRU team in 1975 in the wake of the Los Angeles Police Department’s creation of Special Weapons and Tactics units. The first swat team emerged in the late 1960s following the Watts Riots and the emergence of heavily armed domestic groups, notably the Black Panthers, which taught the LAPD that the standard snub-nosed .38-calibre pistol in the hand of an average cop just didn’t cut it in the face of home-grown terrorism. By 2004, virtually every decent-sized police force in North America had a tactical team.

Today, the OPP has three TRU teams with twelve members apiece. Based in Orillia, London, and Odessa (near Kingston), each costs upwards of $5 million to form and, with additional equipment, maintenance, and training, millions more every year to maintain. As with other swat teams, the TRU mandate includes dealing with barricaded subjects, hostage crises, high-risk warrants, dog tracking, witness protection, court security, and prisoner escorts. Gaining membership is a tough slog. Heinemann and his fellow candidates underwent a two-week selection process that required them to be in tip-top shape and included sleep deprivation and psychological testing. Those who made the grade then went through a five-week training course on the principles of site containment followed by another five-week course on clearing and a three-week course on how to advance on a site. Specialists did additional training—bomb technicians for another nine weeks, rappel masters four, and snipers three. Only a fraction of those who applied made the cut, but once on board they became part of an elite fighting force accorded considerable respect among the rank and file. Heinemann had always been proud he had “the right stuff.”

Heinemann was edgy and dog-tired that early January morning. For the past month, the Barrie TRU had been putting in extremely long days, every day of the week. To make things worse, Heinemann’s two young sons were restless and irritable, and he and his wife, Toni, were hard-pressed to get even three hours of uninterrupted sleep. Heinemann had just returned home after a forty-hour stint, part of which was spent supervising the clear of a massive marijuana grow op in the abandoned Molson brewery building south of Barrie. He had just fallen into a deep sleep when his pager went off.

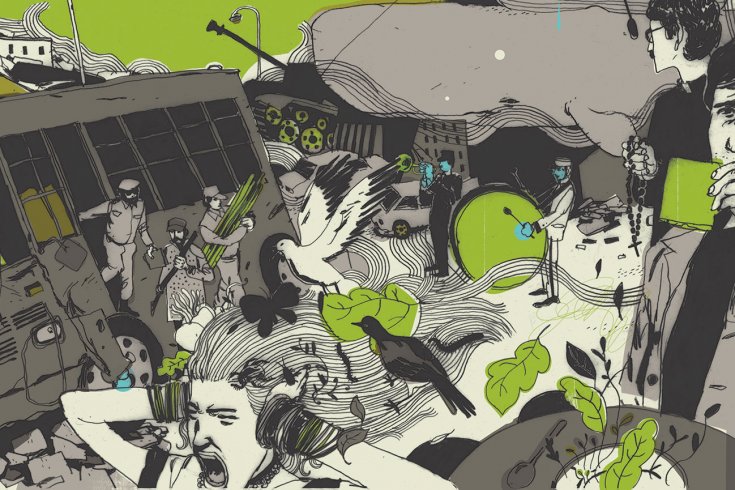

Chippewa conjured up the bête noire of recent OPP history. Located in the southwest corner of the province and only seventy kilometres northwest of the Chippewa of the Thames reserve, Ipperwash had been one of Heinemann’s first calls as a TRU team member. In September 1995, after years of futile negotiations with the government to recover land the Chippewa claimed as their own, a group of about thirty natives from the Kettle and Stony Point reserves occupied a piece of land that had been incorporated into the park. On September 5, the press reported that the government was about to seek an injunction to have the native protesters removed, but they refused to budge. More than 250 OPP officers, including two TRU teams, descended on the park. By the time the smoke cleared, Dudley George was dead.

It could have been any one of the twenty-four TRU members on-site, including Heinemann, who killed George, but Ken Deane was the triggerman, and therefore the perfect scapegoat. Deane was charged with negligence causing death.

The brotherhood rallied to his defence. An annual hockey tournament was established in his name; groups of cops sold T-shirts, stick pins, and other trinkets to raise money; and, most impressively, the membership successfully petitioned the union to add a surcharge to every cop’s monthly dues to help with Deane’s defence. This initiative alone raised almost $1.5 million.

In the criminal trial, Deane was successfully prosecuted. He then pleaded guilty to discreditable conduct following a Professional Standards Bureau (PSB) investigation and resigned from the force. It was a classic application of the “bad apple” approach to problem-solving, and the sacrificing of Ken Deane exacerbated deep divisions within the OPP.

Publicly vilified, in cop culture Deane was a hero. He also walked away from the ordeal with an estimated million-dollar settlement package and an excellent job in the private sector. The more Heinemann learned of Deane’s true fate, the more he thought that Deane ended up doing all right for himself, but that policing was no better off for the ordeal.

In 2003, Ontario’s newly elected Liberal government ordered a formal inquiry into Ipperwash, and it had convened just two months before Heinemann and his crew set off for Chippewa of the Thames. Although it would be July 2004 before the first witnesses were called, the stated rationale for the inquiry—to look into the events surrounding Dudley George’s death and to “make recommendations on avoiding violence in similar circumstances in the future”—made the OPP brass more paranoid and hyper-vigilant than usual. To cops like Heinemann and his teammates, who had been involved in many “similar circumstances,” this was ludicrous: to avoid “similar circumstances” all the OPP had to do was follow sops in confrontations with First Nations people. The Ipperwash inquiry followed TRU cops like Joe Btfsplk’s black cloud. Although Al Capp’s lovable cartoon character meant well, he was a jinx, and now the Barrie TRU was heading toward another confrontation on a native reserve.

The hostile at Chippewa of the Thames was a twenty-one-year-old, cop-hating, dangerous pain in the ass named Aaron Deleary. He had an extensive criminal record and an outstanding warrant on weapons charges. He was also known to be associated with warrior societies, in which shadowy criminal elements had become embedded on numerous native reserves throughout southern Ontario and northern New York.

In the midst of his rampage, Deleary had a phone conversation with First Nations Constable Dan Riley. Peppering his talk with racist slurs and invectives against cops, Deleary said that he was an avenging spirit sent to clean up the reserve. In reality, he and a cohort, a member of the Outlaws motorcycle gang, were trying to kill another low-life named Joey Albert, who Deleary claimed was a crack dealer. This, in Deleary’s view, justified shooting up Albert’s house and van in broad daylight—not to mention the house of old Mrs. Goldsack. (Collateral damage, Deleary said.) Police saw a wack job trying to rectify a drug deal gone bad.

With four women, Deleary and his accomplice barricaded themselves in a modest house at 788 Switzer near a busy convenience store. Band police aren’t equipped to take on active shooters, and Constable Riley followed protocol by calling the band chief, who in turn called the OPP.

It took twelve hours to get Aaron Deleary out—hours not without drama, including a high-speed chase. This distracting and exceedingly dangerous incident could have been avoided had Heinemann’s request to shoot out the tires of the vehicles parked at the target residence—in his view, an sop—not been rebuffed by the Incident Commander, Inspector Kent Skinner, who told Heinemann he would not authorize the discharge of any weapons by the TRU on First Nations territory.

This was Skinner’s first call as an IC, though he was an old warhorse who had been Acting Staff Sergeant in charge of one of the TRU teams at Ipperwash. He knew as well as anyone that tactical teams across North America follow a stringent set of sops. When it came to deploying heavily armed and dangerous swat teams in life-and-death situations, these procedures maximize safety and minimize risk for all concerned. But in order to avoid offending local communities, they are often modified when teams are deployed to Ontario reserves.

As the hours wore on, Heinemann and his team became increasingly frustrated. They received reports from Skinner of people entering the bush lines behind the target residence. Typical of reserves, there was dead ground between houses, and the members of the team tasked with surrounding the house were forced to rotate continuously to cover their backs.

Bystanders were congregating at the roadblocks the OPP had set up, which, contrary to sops, Skinner refused to move out of sight of the target residence. Heinemann made repeated requests that the roadblocks be moved, to no avail. A roadblock in full view of TRU ground operations around a barricaded active shooter with hostages was not simply ill-advised, it was stupid. Worse still, Skinner was letting civilians through the roadblocks to go to the convenience store.

As time went by, the residents at the roadblocks, using cellphones and CBs, began advising Deleary about TRU movements. At one point, Skinner ordered his alpha team to risk the dead ground and deliver a land line to the target residence to facilitate communication with Deleary. Heinemann watched as Deleary stuck his head out the back window and looked right at the alpha team. Deleary could easily have shot and killed any of the officers before being gunned down. A cop was killed at Grassy Narrows and another at Oka, but few even remembered their names. Heinemann wondered how another dead aboriginal malcontent would play at the Ipperwash inquiry.

Deleary finally agreed to surrender. Exhausted, Heinemann stood by the south wall of the living room as his team conducted a “stealth clear” of the wood-frame house. Stealth clears were sop, to gather evidence and ensure that suspects or shooters did not leave any surprises behind. Skinner wanted them to hurry it up. The natives at the roadblocks were becoming increasingly agitated, and Skinner wanted to get the hell out of there. Tired and frustrated, Heinemann eyed a makeshift shrine on the wall next to him. The iconic—and, to many, irritating—image of a camouflaged Mohawk warrior staring down a young Canadian soldier during the Oka crisis was taped to the wall beneath a flag that read “Warrior Society.” Beside them was a peace pipe, a couple of framed family photographs, a white eagle feather, and an Ojibwa dream catcher. Heinemann pulled out his ballpoint pen and stroked two faint X marks across the picture and the flag.

It was Saturday morning, January 24, 2004, and Heinemann’s first full weekend off in months. He was just settling in for some family time when the phone rang. It was Sergeant John Kelsall proposing a secret team meeting to discuss the pen marks. With his square jaw, big nose, and golden buzz cut, Kelsall resembled a plastic action figure as much as a real cop. Nicknamed “Satan” by TRU members, a riff on his devout Baptist beliefs, Kelsall had a Machiavellian side to him. The meeting would be secret because Kelsall wanted it held without the Barrie TRU’s team leader, Staff Sergeant John Latouf.

In policing, chain of command is everything, and for swat units the team leader is god. Heinemann told Kelsall that they weren’t going to call the team in on this rare weekend off, and certainly not behind Latouf’s back. He called Latouf as soon as Kelsall hung up.

A broad-shouldered, career-driven, charismatic man, John Latouf was called “Akhmed” because many in the group thought he looked like a Middle Eastern terrorist. From the tone of their conversation, Heinemann sensed that Latouf already knew about the pen marks. (Later, it occurred to him that Kelsall’s proposal was probably Latouf’s idea, but it would be a long time before he considered the possibility that Latouf had a hidden agenda.) Heinemann apologized for not telling Latouf about the pen marks right after he made them. Latouf was reassuring and told him that he knew Heinemann was only trying to protect him.

Kelsall set up a TRU meeting for Monday afternoon in the basement of the Willow Creek Baptist Church in Midhurst, Ontario. Off the top, Latouf reminded everyone that portions of the communications tapes from Ipperwash had just been released in the media, and they portrayed the OPP as unequivocally racist. As the Ipperwash inquiry gathered steam, the force, and particularly the TRU teams, would be under the microscope. As Latouf talked, Heinemann knew that his stupid, sophomoric pen marks could have serious consequences.

Upset, Heinemann admitted that he had made the pen marks but insisted that they had nothing to do with racism. He said that he and the team were at wit’s end that night, that it had taken twelve hours to get Deleary out of the house, and that had they been allowed to follow sops, lives would not have been endangered and the whole procedure would have been handled safer, faster, and more professionally. They were tired and frustrated. The Xs were meant to speak directly to Deleary and his ilk, those who thought themselves above the law. They said, “You may be able to get away with this bullshit around the band police, maybe even with rank and file OPP, but not with TRU.”

After apologizing, Heinemann said it would be best for him to go to OPP headquarters and fess up. Latouf stunned everyone when he said no. He referred to the Ken Deane petition and upcoming testimony at the inquiry and reminded everyone that since Dudley George’s death, the Barrie TRU had been on probation.

Heinemann left the room to regain his composure and give the others some privacy. Half an hour later Latouf came and got him. Heinemann began to sob. Latouf told him that the group, including Kelsall, had agreed that no one was going to confess anything to anyone. They were going to deal with this matter among themselves. Latouf then said that Heinemann was off the TRU team. That was his punishment. The demotion represented a $30,000 loss in pay. Heinemann was devastated. Adjourning the meeting, Latouf instructed the group to tell anyone who might ask that they were scouting the church for stealth-clear training.

Weeks went by. Nothing was formalized, and Heinemann had no idea what to expect. One day he would be relegated to a desk, the next called on to conduct a training op or ordered to suit up and work an armed robbery. Latouf seemed to be growing increasingly paranoid. He often warned team members not to talk about the church meeting or the pen marks because TRU offices and vehicles were probably bugged.

Tactical-team police favour Suburbans, and after the church meeting Latouf and Kelsall began a series of clandestine head-to-heads in their “Texas Cadillacs.” On the first Thursday in February, Heinemann was asked to join them. Kelsall sat behind the wheel, Latouf in the passenger seat, and Heinemann in the back. Kelsall appeared nervous. He said that he could no longer go along with Latouf’s plan and was going to tell their superiors what he knew. Latouf hit the roof. Kelsall then asked whether TRU teams were becoming like the Hells Angels, making it more important not to rat out other team members than to do the right thing. Latouf went ballistic at the comparison. Kelsall said that he too had committed indiscretions but had never been caught, to which Heinemann replied: “What you’re saying is that it’s okay to commit a crime, for example, killing someone, as long as you don’t get caught, but, if you do, don’t lie about it because lying is wrong?”

Then, suddenly, the rancour between Latouf and Kelsall evaporated. They agreed to contact Inspector Wade Lacroix, a man they both respected, and go with whatever advice he gave them. Formerly a staff sergeant in charge of the London TRU, Lacroix had taken a job as chief of security at the Bruce Power nuclear site near Port Elgin, on Lake Huron. At Ipperwash, he had been in charge of the Crowd Management Unit—the “riot squad” ordered to march, batons banging shields, on the unarmed native occupiers. On the verge of retirement, Lacroix had been drafted to the power plant.

On Tuesday, February 10, 2004, Latouf called the team together to discuss a meeting he’d had with Commissioner Gwen Boniface, head of the OPP. She’d wanted to know what the Barrie TRU might be able to do to help the OPP at the upcoming inquiry. Heinemann thought that the team should finally be debriefed on Ipperwash. Critical incident debriefings are an sop for events involving lethal force, and Ipperwash was the one call in Heinemann’s entire career that had never been debriefed. Someone else pointed out that since Ipperwash—and contrary to the commissioner’s highly publicized First Nations initiatives—most Barrie TRU members had not received First Nations training. In fact, in the eight years since Ipperwash, Ron Heinemann and his teammates had attended exactly four hours of “sensitivity training.” The session involved having everyone sit in a circle and watch while someone lit sweetgrass and passed it around. Each person was instructed to wave the burning grass in front of them, with little further explanation. The team was scheduled for another session, on warrior societies, but it was cancelled.

Driving his wife’s blue compact, Latouf pulled up in front of Heinemann’s house early in the evening on Sunday the fifteenth. Heinemann had no idea, as he folded his six-foot-two inch frame into the passenger seat, that he would eventually find himself testifying about the ensuing events. As Heinemann later told it, Latouf began by saying that he had been talking to someone Heinemann knew, someone much farther up the chain of command. They had decided that Heinemann should write a letter and turn himself in. The letter had to make three points: that no other TRU members had any knowledge of the pen marks; that Heinemann knew he did not have to come forward because a psb investigation would likely go nowhere; and finally, that Heinemann’s conscience was bothering him and he was having a difficult time dealing with the guilt. The second and third points were relatively true, but the first was not. After the church meeting, the entire team knew he was responsible. Heinemann pointed this out, but Latouf maintained that he and his anonymous adviser had concluded that this was the only way to proceed.

Heinemann wrote the letter that night. As he later recounted, when he showed it to Latouf the following day, Latouf ordered him to take out all references to Ipperwash and to him. Heinemann protested. TRU members all wore the albatross of Dudley George’s death around their necks. Ipperwash and what happened to Ken Deane were a big part of the reason Heinemann had done what he did. Latouf said any reference to Ipperwash would generate more difficulties for Deane. This made absolutely no sense. Deane was long gone, rich, and gainfully employed. Latouf told Heinemann that if he were named in the letter it would be obvious that he had something to do with its composition. The letter had to appear as though it came only from Heinemann.

He rewrote the letter that day. Satisfied, Latouf told him to make copies, then dictated exactly what Heinemann was to write in his police notebook: “Staff Sergeant Latouf appeared shocked to receive my letter.”

They headed for OPP headquarters in Orillia. Inspector Tony Cooper, Latouf’s immediate superior, called while they were en route. Latouf said he urgently needed a meeting with Cooper and Cooper’s superior, Superintendent Bob Goodall. Heinemann then overheard Latouf having a brief conversation with Inspector Brian Deevy. “Ron has turned in a letter and we are on our way to ghq,” Latouf said. This led Heinemann to think that Deevy might be Latouf’s unnamed confidant (though Latouf would later state that Deevy was not). Heinemann believed that Deevy, Latouf, Deane, and Lacroix were close, and given that Deevy was then the commissioner’s executive assistant, Heinemann even imagined that Boniface might be in on it too.

Just before they arrived, Latouf pulled off on a side road. Heinemann testified that Latouf directed him to hand over the original letter the same way he would if Latouf were sitting at his desk in the office, in case the internal investigators had the envelope and letter dusted for their prints. The cover-up seemed complete.

An architectural anomaly in an otherwise two-storey town, OPP headquarters in Orillia recalls the Crystal Cathedral, home of the evangelical television show Hour of Power. On March 11, 2004, the OPP held a press conference there to announce that eight members of the Barrie TRU—Heinemann, Latouf, and constables Sean O’Rourke, Jason Kummer, Al Penrose, Cam Cooper, Alex Zapotoczny, and Brad Traves—had been charged under the Police Services Act (psa) with “discreditable conduct” and “deceit” stemming from the conspiracy to hide the vandalism at the Chippewa on the Thames reserve. The OPP’s spokesperson, Superintendent William Crate, declared that racism would not be tolerated by the force.

Heinemann was stunned. He and Latouf were suspended from duty; the other six officers were reassigned. Heinemann couldn’t believe what he had just heard. First, the whole purpose of the ruse was to save the team by having him take the fall. Second, as TRU officers frequently deal with organized crime, their identities are closely guarded. In this instance, the OPP named names, not only endangering the lives of officers but also their wives and children. Then Crate dropped the bomb: the OPP was disbanding the Barrie TRU.

Within a month of Heinemann and Latouf’s suspensions, the OPP dropped the charges against Latouf. He negotiated a rich settlement package and almost immediately went to work for Wade Lacroix at the Bruce plant. A sweet deal for him, but Heinemann was left twisting in the wind. As it turned out, Latouf made a point of staying in touch. On May 11, 2005, he made one of many calls to Heinemann after the disbandment. “When I talked to you yesterday,” he told Heinemann, “I was in my office and couldn’t talk. I was trying to tell you if you put Brian Deevy on the stand, testimony will get fragile.”

Heinemann’s psa hearing was about to begin. Once it got under way, the OPP advocate, Denise Dwyer, insinuated that he was a racist and referred to him as a “liar” and a “coward.” Dwyer made it abundantly clear that the OPP would settle for nothing less than Heinemann’s job. Humiliated on a daily basis during the hearing, Heinemann held out hope that Latouf would agree to testify on his behalf.

Heinemann learned many things from witnesses called by the OPP. Aaron Deleary, who testified by video link from a jail cell, had been held for less than two days after the Barrie TRU arrested him back in January 2004. Heinemann was surprised when Deleary, chuckling, said he understood the pen marks as a straight “fuck you” from cop to native. He also discovered that Professional Standards Bureau investigations are only supposed to be initiated after formal written complaints, but despite many opportunities and inducements Deleary never submitted a written complaint to either band police or the OPP. The house in which Deleary had been barricaded was being rented from the Rileys, and Deleary had moved in two weeks before the incident. It was Chief Kelly Riley, Constable Dan Riley’s uncle, who had contacted the opp and described the pen marks as vandalism. A full-scale psb investigation followed—one that the lead investigator described under cross-examination by Heinemann’s lawyer, John Rosen, as the most intense and far-reaching in his experience.

Most importantly, Heinemann discovered that Kelsall and Latouf had been fully aware of the investigation when Kelsall called Heinemann that Saturday to propose the meeting at the church. During his testimony, Dan Riley also confirmed that the warrior flag was all about outlaws, defiance, and disrespect for authority. The flag was ubiquitous on the reserve, Riley said, but only criminals and malcontents displayed it.

As the case wore on, Heinemann became increasingly mistrustful. He started to believe there was a grand conspiracy afoot—one that might even include Rosen—to portray him as a lone, rabid racist who had been heroically rooted out by the opp on the cusp of the Ipperwash inquiry.

In early July, shortly after the OPP concluded its case against Heinemann, Latouf told Heinemann he would testify for him, but only in camera0—an offer that was unfeasible given the public nature of psa hearings. Media reports about his settlement package had already caused him heat at work, he said. Although Latouf remained at the top of his wish list, Heinemann identified many individuals he wanted called in his defence, including the commissioner herself, Inspector Deevy, Chief Riley, even the psychiatrist who had examined him. He presented the list to Rosen, one of the most prominent defence lawyers in the country, but was made to understand that calling these people would do more to harm his case than to help it. Ultimately, Rosen put only Heinemann himself on the stand.

psa hearings are more constrained than criminal trials, and in Heinemann’s case the finding hinged not on whether there was reasonable doubt that his actions constituted racism, but rather a straight either/or finding based on clear and convincing evidence that he broke OPP protocols. On October 28, 2005, the hearing adjudicator found him guilty of discreditable conduct and deceit. While the ruling was harsh, the adjudicator did conclude that there was no racial intention behind the pen marks. This was a huge victory for Heinemann.

Immediately after the ruling, Rosen brought a motion to compel the OPP to produce the details of all the settlements made with various Barrie TRU members, including John Latouf and Ken Deane. Rosen argued that these settlements (which left both men unscathed and enriched) were essential to inform the adjudicator’s deliberations about what punishment, if any, Heinemann should receive. Naturally, the OPP vigorously opposed his motion, and in December the adjudicator ruled against it. Rosen then appealed to the Divisional Court, which took the matter out of the cloistered world of a psa hearing and the OPP’s general headquarters.

The OPP was heavily invested in the widely held perception that Ken Deane was a bad apple who had been plucked out of the basket and discarded. The last thing it wanted made public were the details of what Ken Deane actually received after the Ipperwash case or information about John Latouf ‘s settlement package. And the organization’s lawyers feared that Rosen’s appeal would succeed.

In mid-January 2006, Heinemann received an offer via the Ontario Provincial Police Association (oppa) that would allow him to keep his job. The terms were as follows:

(1) Demotion from first-class to fourth-class constable with a work-back schedule within the usual time frame—a matter of years. Overall, this would amount to an $80,000 loss in pay.

(2) A transfer, selected from a set list of detachments. This meant that Heinemann would have to move his family out of the Barrie area.

(3) Participation in a native healing course.

Heinemann was given until January 25 to make a decision. If he did not accept the offer, the union would cut off his legal funding.

The unfairness was overwhelming. Heinemann’s psa hearing had not even run its course. The oppa had spent over a million dollars in legal fees on Ken Deane. Heinemann’s situation was different, but he nevertheless wondered if the reward for gunning down a native protester was far greater than putting pen marks on their flags and pictures. Nut Island was closing in on him.

At the annual OPPA President’s Meeting, held at the Kempenfelt Conference Centre in Barrie on January 19, 2006, Ron Heinemann and his wife sat down to lunch with Heinemann’s union rep, Jim Christie. Christie had good news: the OPPA had decided to pay for the judicial appeal after all. Toni Heinemann, a sharp-witted, tenacious fighter from a large Italian family, said this was good because her husband had no intention of accepting the OPP’s insulting and punitive offer. If Heinemann took what the OPP had put on the table, not only would he be back where he started twenty years earlier, he would also be conceding that he was a racist and a liar. Instead, Toni and Ron were going to the media, any politician who would listen, and also to the Ipperwash inquiry, where they intended to publicly confront the commissioner on the day she was scheduled to give a presentation in advance of OPP members testifying, January 26.

These declarations precipitated days-long telephone marathons. Heinemann spoke in depth with the president of the oppa, Karl Walsh, who wanted to know if he still wanted to wear the uniform or if he would consider resigning and accepting a financial settlement. If the latter, how much should they negotiate for? A million dollars? More?

Walsh also cautioned that what Heinemann was planning to do at the inquiry could have a very negative effect on dozens of senior officers. But the Heinemanns were resolute. The night before the commissioner was scheduled to make her presentation, Latouf called the pair. He spoke to Toni and warned the Heinemanns not to proceed, saying they would regret it if they did.

The couple decided to go ahead with their plan. They were overnighting at Ron’s parents’ house in Hamilton when, just after midnight, their lawyer reached them with word of the OPP’s latest offer: a demotion to third class with a swift return to first class. This represented only a $12,000 loss in pay. The new offer included a transfer to the Huronia West detachment in Wasaga Beach, meaning Ron would not have to uproot his family. The OPP remained adamant about the native healing course, but surely that was not a major stumbling block. Heinemann said “no deal.”

Early in the morning, Karl Walsh called and strongly advised Heinemann to think about what he was doing. He said Heinemann still had time to give them the right answer.

Heinemann walked into the inquiry just as the commissioner began her presentation. During the first recess, Walsh told him that the healing-course requirement had been dropped from the offer. Even with this welcome news, Heinemann felt drained. He wasn’t hard-wired for high-profile confrontations. The same couldn’t be said of his wife. The politicians, the media, and the proposed faceoff with the commissioner were Toni’s ideas, and she intended to see her husband follow them through.

Nonetheless, if what Walsh said was true, Heinemann said he would take the deal and leave. Walsh assured him he had just spoken to the commissioner’s lawyer and it was agreed: the OPP would drop the healing course. Despite Toni’s protestations, they left the inquiry. Heinemann signed the deal in the early evening on Monday, January 30, 2006, in the oppa offices. There was one additional condition: the judicial appeal for the disclosure of Deane and Latouf’s settlements would be abandoned. Heinemann agreed.

In 1994, New York City’s Mollen Commission advised that the practice of sacrificing individual police officers as a method of solving problems was counterproductive and corrosive. The commission’s report stated that the root problems that plague law enforcement are embedded in the culture. The report described the manner in which those in senior police command routinely use the bad apple theory to avoid confronting systemic problems. Mollen noted that it would be impossible for the nypd to make a lasting commitment to integrity without the help of independent external oversight. The commission recommended that scapegoating be abandoned.

Resigned to his fate and fairly sure he could put everything behind him, Heinemann awoke early on February 28, 2006. He turned on the radio to hear that he alone was responsible for the disbandment of the Barrie TRU. The reports provided the details of his plea agreement from the worst possible perspective.

Heinemann went a little nuts. He made phone calls, wrote myriad emails and letters to try to correct the public record, but nothing changed. Time passed. During the summer Heinemann patrolled Wasaga Beach and made up his lost $12,000 by working on the side as police security for local clubs. Today, Heinemann has regained his full rank and pay. He was recently elected the Huronia West detachment’s union rep.

Shortly after the Barrie TRU was disbanded, the OPP dropped Culture and Change as required reading for the sergeant’s exam. The OPP publicly stated that the Barrie TRU would not be reconstituted, but a few months later a new team was formed thirty kilometres up the highway, at the Crystal Cathedral. None of the original Barrie TRU members were recruited.

On February 25, 2006, Ken Deane had been killed in a traffic accident, shortly before he was to testify at the Ipperwash inquiry. Soon after, Commissioner Boniface was appointed to a police board in Ireland and left the OPP.

After commissioning more than twenty major research papers from academics and other experts to help it understand the issues, granting thirty-one parties standing, and hearing testimony from 139 witnesses and representations from 110 lawyers over 229 days, enumerating 1,876 exhibits and creating a database of over 23,000 related documents, putting together a verbatim record of the hearings that amounted to 60,000 pages of transcripts and a video of the entire proceedings, the Ipperwash inquiry finally wrapped up in late August 2006. It cost over $19 million, paid in full by Ontario taxpayers.

In the wake of Boniface’s resignation, the government intervened and appointed former Toronto police chief Julian Fantino commissioner of the OPP. Fantino has been a police officer for over forty years. His record and his public statements suggest that he is one of the staunchest proponents of the bad apple theory and its application in policing today.