Luc Ferrandez’s last bicycle was a Kona, a sturdy model with thick tires, ideal for hauling heavy loads. During his 2009 campaign as the Projet Montréal candidate for the Plateau-Mont-Royal borough, he would hook it to a trailer piled with a laptop, a projector, a collapsible screen, and (this being Montreal) a couple of bottles of rosé. After setting up his equipment next to a café terrace or a depanneur, he would distribute paper cups and launch a PowerPoint slide show of streets and squares in Copenhagen, Paris, and Madrid, as well as historical photos of local boulevards, all unencumbered by traffic. He figures it was these partys de trottoir, or sidewalk parties—during which he made the case that Montreal could be as clean, green, and safe as any place in Europe—that won him the mayoralty of the city’s most populous district. (Each of Montreal’s nineteen boroughs elects its own city councillors, one of whom also serves as the local mayor.) His mountain bike, alas, didn’t survive the campaign.

“I was having a discussion with a citizen,” recalls Ferrandez, whose shock of thick brown hair and long-toothed smile get turned into a pompadour and a chipmunk grin by Quebec’s editorial cartoonists. “I left my bike against a wall, unlocked. When I came back an hour later, it was gone.” These days, his main mode of transportation is an Opus, which, though designed and built on the island of Montreal, has the upright handlebars and broad saddle of a bike you would expect to find leaning against a canal-side railing in Amsterdam.

One afternoon last fall, the mayor of the Plateau pedalled his new bike down avenue Laurier, whose bistros and bocce pitches make it feel like one of North America’s most European promenades. In the shadow of the verdigrised spire of the Catholic church on the corner of rue Berri, a woman in high heels returned a Bixi, one of Montreal’s fleet of 5,000 loaner bikes, to a stand outside the Laurier metro station. The brisk bicycle traffic in the recently broadened curb lanes moved smoothly. Between the bikes, cars idled, backed up for blocks. A few months earlier, Ferrandez’s party had restricted automobile traffic on Laurier east of boulevard Saint-Laurent to one eastbound lane.

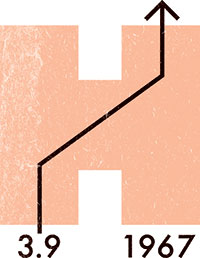

Left Behind

Swedish drivers modernize

Robyn Shesterniak

For over 200 years, Swedish residents drove on the left side, while the rest of Scandinavia kept to the right. (Left-hand traffic historically made sense for right-handed swordsmen, who preferred to pass enemies on the side of their fighting arm.) Even though most Swedish cars were built for right-hand driving, the majority of Swedes—83 percent, according to a 1955 referendum—favoured the left. In 1963, the national parliament decided enough was enough and enacted a mandatory switch. During the wee hours of September 3, 1967, 360,000 Swedish road signs were replaced, and at 4:50 a.m. the country’s traffic ground to a dead stop. At the stroke of five, drivers tuning in to a radio countdown heard the words “Now is the time to change over.” And they did.

—Amirah El-Safty

“This is just the beginning,” said Ferrandez, pausing outside an elementary school to put a foot down. “On this block, we are going to plant sixty trees and add a little market. We are also going to expand the sidewalks by six metres, which will protect the school and make it easier for parents to fetch their kids.” He acknowledgedthat this move would also make life even more difficult for drivers in Montreal.

For fans of contemporary urbanism, Ferrandez has been heaven sent to resurrect the Plateau, surely Montreal’s most emblematic neighbourhood. Located north and east of downtown, it encompasses the smoked meat–scented alleyways of Mordecai Richler’s Mile End; and, around Parc La Fontaine, the twisty-staircase-fronted triplexes dear to Michel Tremblay. Despite a real estate boom (condo prices have doubled since the ’90s) approximately three-quarters of its residents remain renters. The Plateau averages just 0.6 cars per household, versus 1.5 in the rest of Canada, according to the borough’s own 2008 study. Even so, its narrow streets are especially congested because of commuter traffic between the office towers of downtown and such automobile-dependent suburbs as Laval. Some 80 percent of the cars using the borough’s streets come from outside it.

Ferrandez’s power is limited; City Hall, led by Union Montréal’s Gérald Tremblay for the past decade, has the ultimate say on major infrastructure projects. But the boroughs do have the power to determine the direction of one-way streets, and Projet Montréal has focused on creating traffic mazes that channel drivers back to such major arteries as rue Saint-Denis and Saint-Laurent. These calming measures come at a time when Montreal’s roads, sewers, and gas lines (not to mention its bridges and tunnels) all seem to be reaching their best-before dates, provoking a spate of construction that threatens to paralyze such north-south thoroughfares as avenue de Parc and avenue Papineau for years to come. The result, in the summer of 2011, was borough-wide gridlock. As Bixi riders wove around immobilized cars, talk radio callers lambasted Montreal’s most visible, and vocal, opponent of the automobile as a dictator, a Nazi, and even Satan.

“I accept that some people think I’m the devil!” Ferrandez shouted over his shoulder, making a right onto rue de Brébeuf. “For them, the Plateau doesn’t exist. It is just a place to be driven through. I don’t give a shit about these people. They’ve abandoned the idea that humans can live together.” Even among his constituents, there are signs that Ferrandez may be moving too quickly. Shop owners, hard pressed by property tax increases, claim that congestion and higher parking meter rates are driving customers away.

Ferrandez’s vision of what the borough is, and could be, seems almost exalted. “The Plateau is an Italian cathedral. It’s a forest. It’s something to protect, something sacred. I don’t want it to become a place where people come to live in a condo with triple-glazed windows for a couple of years. This has to be a place where people can be comfortable walking to the bakery, walking to school, walking to the park—where they want to stay to raise a family.”

At forty-nine, Ferrandez is a first-time father, and the Projet Montréal message seems to resonate most loudly among new families. The upstart party was founded in 2004 by a coalition of environmentalists whose leader, architect and urban planner Richard Bergeron (author of Le livre noir de l’automobile, a book-length diatribe about the impact of cars on society), won less than 9 percent of votes the following year when he ran for mayor on a pro–sustainable urbanism and anti-sprawl platform. In the 2009 election, Bergeron’s share of the popular vote rose to one-quarter; fifteen of the city’s sixty-four councillors now belong to the party.

After following a path slick with fallen maple leaves into Parc La Fontaine, Ferrandez dismounted outside a restaurant overlooking an artificial lake. “With everything I’m doing,” he said, leaning his Opus against a tree, “I may lose the next election. That’s why I have a real sense of urgency. If I only have two years left, I want to get as much done as I can.” This restaurant, he said, was an example. Using the money saved from delaying snow removal after one late-winter storm, the borough converted a deserted pavilion, formerly a stroll for teenage prostitutes, into a kind of Tavern on the Green. Its terrace is now a popular summer destination. Inside, Ferrandez shook hands with a waiter before wandering off to talk to some women who were finishing their lunch.

“What’s a snowstorm?” mused the waiter. “A couple of days, and it’s finished. This place is going to be around for twenty years at least.”

Eventually, Ferrandez returned from his chat with the citizenry. He hadn’t bothered to lock his bike, but this time it was still waiting for him.

This appeared in the March 2012 issue.