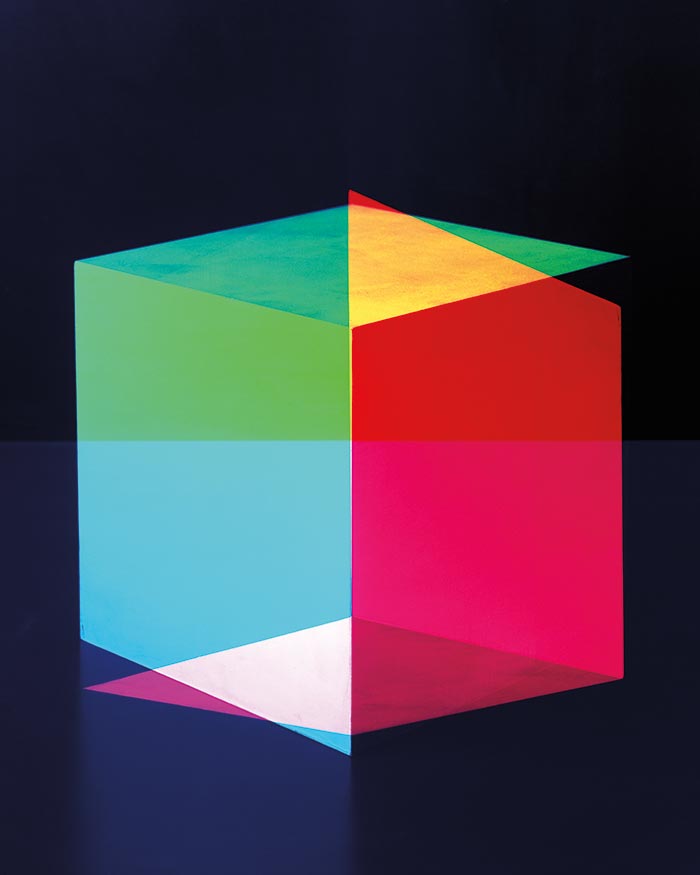

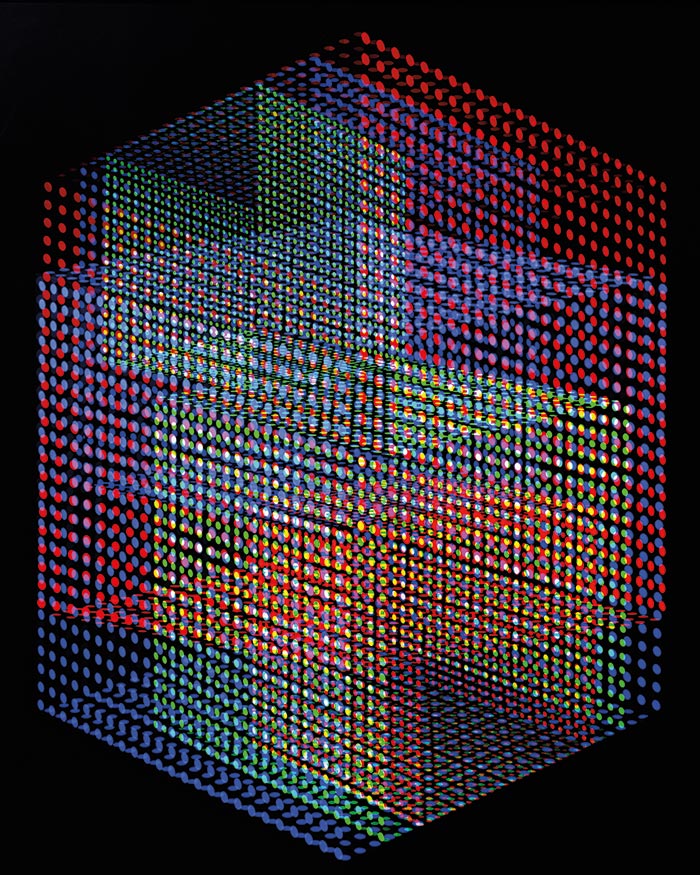

Regina-born, Vancouver-educated Jessica Eaton is a Montreal-based artist who works primarily in photography and lens-based images. She shoots made objects, creating photos that use colour in surreal ways. This leads many to think she’s actually a painter. Read an extended analysis of her work in the magazine’s “Five Contemporary Artists to Watch”—and my interview with her below.

Brian Morgan: I’m curious to know what you think about colour.

Jessica Eaton: At this point, I can mix any colour I want. Is there really such a thing as a bad colour combination? The worse they are, the more interesting they are to look at. Which is also intriguing, because there so many comparisons to painting, and I get talked about a lot in that context. For me to choose the colours [as a painter might], I would choose my [preferred] palette from when I was eight years old, like, “Turquoise and pink are great together!”

Brian Morgan: If you put a bunch of colour chips in front of people, most of them will choose the same ones every time.

Jessica Eaton: Exactly. I’m really freeing myself from that, and I’m forced to accept [the results]. What happens is often better than my will, and the false beliefs that I’ve come to through my life, about what colours should be together.

Brian Morgan: Let’s talk about abstraction. I find it very interesting that there is a return to abstraction in photography. It’s almost like everybody acknowledged that photography could be an art a little late, and now you’re allowed to do whatever you want. But it’s funny because photography started out as abstraction.

Jessica Eaton: Very abstract! I’m spoken about a lot in the context of making abstract photographs, which I don’t believe I’m doing. With the formal elements, they have this aesthetic semblance to really heavy, very familiar canons of modern art. It makes sense it would go there. But in terms of the medium of photography, I don’t think I’m doing anything that functions in the abstract. If anything, it’s maybe hyper-real, actually. I’m taking in information that is there.

Brian Morgan: So maybe it’s more analogous to scientific photography, which is a confrontation with the real world, but…

Jessica Eaton: Sort of, but scientific photography has a purpose.

Brian Morgan: Do you have a point in mind?

Jessica Eaton: Not really, I want to ask more questions. I want to see a photograph that I didn’t previously know. Photography was never that real. I would argue all photographs are abstract. And we got lost thinking there was this realistic authority to the medium.

Brian Morgan: Are you talking about how there’s a supposed one-to-one correlation between a picture of a person and a person?

Jessica Eaton: Sure, but even of a building. An example I like to use—if you look to film, there’s a move called the dolly zoom, which is famous from the film Vertigo. And what happens there is you have a subject in the centre, and a zoom lens on your camera. And you move the zoom while you move the camera, so your photo length is switching, as well as the camera’s position. So you are able to keep your subject the exact same size as you move your frame. But the difference between the long lens and the short lens is that it completely collapses the background. It’s so insane when you watch it in motion, that it make you feel physically ill. And the camera created that.

But when we look at a still image, we naturalize, we think “this is a photo of this building, this is what it looks like.” The reality is, there’s a multitude of versions, depending on what lens you are using. A two-dimensional photograph can turn out so many ways, it’s not a fixed reality.

Brian Morgan: There’s a super-realism there.

Jessica Eaton: Something that interests me a lot about photography is not in how photography sees like we do, but how photography sees like it does, and what it shows us that we can’t perceive. With human perception, we only see a tiny bit with our lens and our brains.

When I was young and just starting to make photographs, I got a job at a one-hour photo lab. It was at a mall in Vancouver. I worked there for all of three weeks. My initial thought was, “This will be fascinating, I get to see all of these people’s photographs!” We were the closest one-hour lab to the harbour, and we had a deal with the cruise ships when they would dock in Vancouver—these were the Alaska cruise ships, for the most part. We would get these rushes when the cruise ships would dock, and on the ships they sold disposable cameras, which were all identical.

And people would bring in the same photos. You could have given any person someone else’s film and they would not have known the difference. Because they are so taken by the glacial Alaskan coastline, so they weren’t just using the same machine, they also took it from the same vantage point. Next the rail of the ship, close as they could get. No one took photos of the people they were with, they were all of the landscape, which I’m sure was beautiful when you were there, but the photos were awful, and all identical. Thousands and thousands of the same picture, same scene. It really struck me. When you’re looking at that coastline [in real life], you also have the feeling of the cool air on your face, and what you had for lunch, all of these other things. All that you’re perceiving, not just with your eyes, but also with your brain. You can take a photo of that scene, but only if you learn to manipulate the camera to bring in symbolic elements. It’s not just there readily when you push a button, and our perception of it is not what you get back in those pictures.

[breakline]

This gallery of Canadian contemporary art is proudly supported by TD Bank Group.