Browsing the arts and culture pages of various websites recently, I kept running smack into it: the first-person pronoun, as conspicuous as a Corinthian column. It sprang up in essay after essay—and right behind it, a critic in the mood to share. Many of these essays were ostensibly works of criticism about some artist or cultural product. But each one seemed to be armed with a selfie stick, aimed at the essayist. Here are some of their sentences:

- I was thirteen in those pre-Internet days when you needed a cool friend or sibling to introduce you to new music, especially in smaller cities like my hometown of Winnipeg.

- Fukien (or Fujian) is my mother’s home province, the place she and her parents immigrated from in the 1950s. So when I hear “Fukien,” I’m not thinking about a cuisine. I’m thinking about the place my family came from, and of the long history of migration that they’re a part of.

- Maybe I’m a self-flagellating weirdo, but pretense is a personal tendency of which I’m all too acutely aware.

- The first time a girl ever called me pretty, she was absolutely stoned.

For the record, the pieces that play host to these sentences are about: the rock band The Replacements; a recent New Yorker poem by Calvin Trillin; Dan Fox’s book Pretentiousness: Why It Matters; and the late singer-songwriter Elliott Smith. But I could’ve pointed to plenty of other recent examples of critics pointing at themselves.

Contemporary criticism is positively crowded with first-person pronouns, micro-doses of memoir, brief hits of biography. Critics don’t simply wrestle with their assigned cultural object; they wrestle with themselves, as well. Recent examples suggest a spectrum, from reviews that harmlessly kick off with a personal anecdote, to hybrid pieces that blend literary criticism and longform memoir.

Some of these pieces are certainly excellent, and, as an editor, I’ve certainly commissioned my share of what might be called “confessional criticism.” I’ve even written some, too. But—confession!—I’ve never felt especially good about it. Relating works of art to one’s life, after all, is easy. (No reference library required.) Moreover, the confessional voice is dangerously attractive; as Virginia Woolf put it, “under the decent veil of print one can indulge one’s egoism to the full.” Such a voice doesn’t necessarily guarantee more honest criticism, and, in some ways, its subtle designs on the reader make it even more deserving of our wariness.

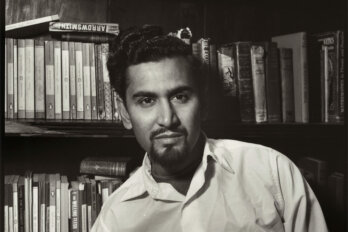

How did our critics get so confessional? At mid-century, a group sometimes called the “New Critics” enclosed themselves in an impersonal style, a Darth Vader mask through which they filtered their analyses. Figures such as Northrop Frye believed that works of literature had allusive tendrils in one another, forming a vast, apprehensible system—and so the aspiration was to sound objective, like a botanist scrutinizing roots. Even those not officially associated with the movement, like Edmund Wilson, found it useful to leverage the clinical language of science, which supplied a sense of authority. “It is my purpose in this book to try to trace the origins of certain tendencies in contemporary literature and to show their development in the work of six contemporary writers,” he declares at the start of Axel’s Castle, his celebrated study of Symbolism. Peak chill would be achieved by the theory types—Jacques Derrida and Judith Butler, for instance—whose voices came packed in dense jargon that required a doctorate to chisel through.

There were always alternatives, of course, running parallel to the more imperious critics. Dorothy Parker deployed a chatty, engaging avatar in her book and theatre pieces. Randall Jarrell’s poetry criticism, Pauline Kael’s film reviews, and Lester Bangs’s music writing all seemed fired by irrefutable furnaces: living, breathing personalities.

Although many of these critics weren’t strangers to the first-person pronoun, they often only appeared to write in a personal voice; their reviews and critical essays revealed little about themselves. If anything, they tended to favor a hollow I, a handy prop like the cardboard tube that girds a few yards of giftwrap. It’s the sort of pronoun I’ve employed here, meant to give voice to an argument as opposed to a person. An I that’s a close, less clinical cousin of “one.” A convention, a convenience.

But in recent years, there’s been a surge in confessional criticism. This can probably be traced to several things: our declining belief in a tradition or canon (whose dead white masterworks once ensured that critics shared a set of reference points outside the self), the exodus of writers towards the Internet (which enables the immediate posting of one’s personality), our ever-metastasizing regard for pop culture (which demands a critical response of commensurate informality), and, of course, David Foster Wallace.

Wallace wasn’t primarily a critic, but the critical essays he published in the 1990s and 2000s presented a model to my generation. He eschewed irony, embraced sincerity, and choppered himself into his analyses of assorted cultural phenomena. “Today is Press Day at the Illinois State Fair in Springfield,” begins an early essay, “and I’m supposed to be at the fairgrounds by 9:00 a.m. to get my credentials. I imagine credentials to be a small white card in the band of a fedora.” The voice Wallace patented—endearingly amateur, impressively brainy—couldn’t help but appeal to other writers, especially younger ones. Half wide-eyed, half winking, it supplemented deep learning with self-deprecation, a colloquial tone, and personal experience. When he wrote about the politics of dictionaries, Wallace brought up a difficult encounter with a student. When he analyzed the films of David Lynch, he recalled the night he saw Blue Velvet for the first time.

Many of today’s most prominent critics seem to spring from Wallace’s DNA. They call attention to their foibles, embrace sincerity, and locate cultural objects in relation to their own lives. Consider the opening of Leslie Jamison’s essay about James Agee, from her influential collection The Empathy Exams (2014):

Many nights that autumn I went to a bar where the floor was covered with peanut shells, and I drank, and I read James Agee. Liquor carried his trauma all through me, twisted me pliable to the loss, and I wasn’t afraid to think like this—pliable to the loss—because I was drunk, and drunk meant sentiment was not only permissible but imperative.

Jamison begins with a personal anecdote, brings in Agee, and then swiftly flushes out the potentially objectionable lines (like “pliable to the loss”) before the reader can object to them. She moves on to discuss Agee’s book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, but discusses herself, too: the aftermath of a recent assault, a move to New Haven. “So I read Agee thinking about his own guilt when he was supposed to be thinking about three Alabama families, and I thought about myself when I was supposed to be thinking about Agee.”

On its own, this can seem like engaging, moving stuff. As part of a trend, it blends into a choir of exceedingly competent critics who can’t seem to keep themselves out of their sentences. For example, there’s Geoff Dyer, who has written several books in this vein: one about his obsession with the film Stalker, another, about his failed attempt to write a book about D. H. Lawrence. (Dyer claims he’s allergic to Wallace, but the striking resemblance has been noted.) Then there’s John Jeremiah Sullivan, who can’t write an essay about the meaning of Axl Rose without showing up as the supporting act. “I’d been shuffling around a surprisingly pretty, sunny, newly renovated downtown Lafayette for a couple of days,” he writes, of the city where Rose was born, “scraping at whatever I could find.” Like Jamison, Sullivan is careful to remind us that, next to civilians, writers are indecently self-interested.

Then there’s Carl Wilson, who examines a loathing for Celine Dion’s music in his oft-celebrated book Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste (2007). Wilson offers engaging readings on how taste is constructed and why our culture distrusts sentimentality. But he also feels moved to describe the afternoon his “future exwife” sang some Buddy Holly to him, thawing the one-time snob’s heart. “I don’t think I have ever been moved, even in our wedding vows, by a profession of love,” declares Wilson. “I’ve seldom felt so honored, so human, so sure that merely human was enough.” The chapter closes with something like the climax to a power ballad: Wilson screwing up the nerve to finally review Dion’s blockbuster album Let’s Talk About Love. “All right, Celine, I’m ready. Bring it on.”

Your tolerance for this sort of thing is, of course, going to be personal—largely a matter of stomach acid (yours) and style (the critic’s). But style only goes so far. A critic’s desire to ensure that she comes off as messily human may come from an honest place, but it’s hard to distinguish seemingly sincere moments of self-critique—“I was supposed to be thinking about Agee”—from rhetorical strategies designed to win readers over. “I’m not the most reliable narrator,” writes Katy Waldman in a recent, stylish essay about anorexia narratives that’s part memoir, part lit-crit. But the unreliable narrator is a cliché, and such confessions have long since become codified and suspect. Put another way: copping to unreliability is a quick, painless way to earn your reader’s trust and, well, prove your reliability. Even Wallace himself worried about the efficacy of self-reflexivity.

None of this is to suggest that critics should sink a dentist’s sharp into their prose, inject artificial chill into their voice, aspire to the frozen state of Eliot, Adorno, and the like. But they should want to be wary of the zeitgeist. If criticism has reached peak confession, critics would do well to simply scrutinize the cultural product at hand (as well as its influences, social context, and, yes, tradition; we need to read beyond ourselves) and put a temporary moratorium on the memoir—especially if the picture painted is of a quirky, sincere, self-deprecatory soul.

Reviews and essays that call attention to the critic are kind of like those movies that insist the viewer wear 3-D glasses. They promise depth, middle distance, a more fulsome experience, three-dimensionality: some additional layer of life. But the promise is redundant. Good criticism, like good films, will always give the impression of depth, of a presiding, trustworthy personality. Smart sentences, one after the other, are usually heartbeat enough.