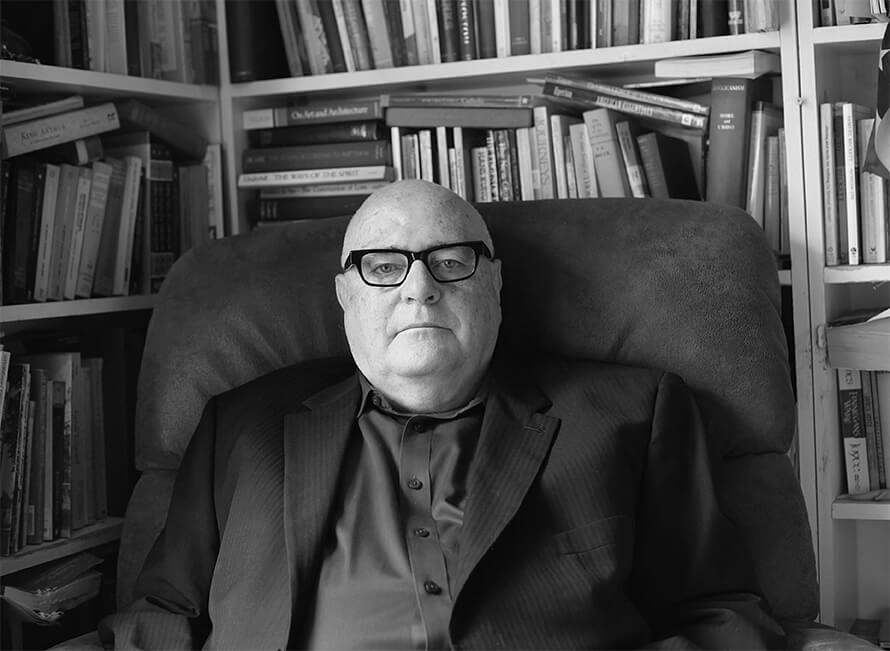

Having a conversation with John Bentley Mays, who died suddenly while on a walk with friends in High Park in Toronto last Friday, could be a disorienting experience. First of all, his bald head was unusually large and bulbous, as though made to be chiseled from marble, and his eyes, gazing out from behind glasses with thick black rims, had a fixed, unblinking attentiveness that rarely betrayed where his singular mind was roaming.

But despite his seemingly imperious—if not impenetrable—presence, his voice was disarmingly gentle and had a distinctive drawl. Though by the end he had spent more than half his life in Toronto, a city he loved and explored deeply, Bentley Mays never lost the quality of being a southern gentlemen, an enduring trace of a complicated childhood on a crumbling cotton plantation in America’s deep south. “When I first read Faulkner,” he once told me, “I really thought I was reading about my childhood.”

While still a graduate student in literature at the University of Rochester, Bentley Mays moved from upstate New York to Toronto in 1969 in order to teach humanities at York University. By 1973, he had decided, as part of a New Year’s resolution, to become a writer rather than a scholar. In retrospect, that should have come as no surprise: Bentley Mays’s temperament was far too poetic, restless, and mercurial to fit comfortably within the confines of academic life. He spent the ensuing years writing poetry and fiction, publishing the novel The Private Stair in 1978 and even performing as the cross-dressing Private Dyke at the Video Cabaret in the early days of the influential artist-run centre A Space Gallery. Then, in 1980, and to his amazement, he was offered a job as the art critic for the Globe and Mail.

The 1980s were an auspicious time to become the art critic for a daily publication with the ambition to cover the national and international scene. By 1980 Canadian art—a loosely defined swath of creative activities from painting and sculpture to video, performance, installation, and everything in between—was taking on increasing national and international importance, and Toronto was its center of gravity. Bentley Mays held the position for eighteen years, until he was lured away by Conrad Black and the new National Post. The job, which came with an even more expansive mandate and a better expense account, kept him on the road between France and Germany and Vancouver, Winnipeg, Halifax, and the Arctic. The National Post let Bentley Mays go in 2001, when the financial reality of paying for a first-rate culture writer—and the financial reality of running a daily in the twenty-first century—hit home.

For twenty years, Bentley Mays was the most prominent, courted, and feared writer about art and culture in Canada. But he was never anything like an ordinary critic, and his work remained irreducibly, and to many infuriatingly, personal and idiosyncratic. Bentley Mays came from a generation, in the shadow of prominent New York art critics like Clement Greenberg and later Rosalind Kraus and Michael Fried, where writers about art were expected to be allied with prescriptive aesthetic movements. That kind of ideological relation to art, or to life for that matter, was alien to him.

Bentley Mays encountered the best in art, whether that was the performances and installations of General Idea, the photographs of Jeff Wall, the lush and ruminative paintings of John Brown, or the elaborate collections of images and objects assembled by his friend, the collector, curator, and artist Ydessa Hendeles. He regarded art with a sense of wonder, as singularities and opportunities for experience, encounters in which the world is illuminated and made meaningful—certainly not as occasions to confirm a philosophical point much less a political thesis.

Bentley Mays wrote about art as part of human experience and the quest for meaningful lives, which may be one of the reasons why, later in his career, it was so natural for him to write about architecture and urban planning, from tall buildings to intimate private homes. The built environment, after all, is one of the principal ways in which our experience of everyday life is shaped. I don’t think Bentley Mays made a sharp distinction between art and architecture, between an ambitious painting and an elegant, but humble shed he might encounter on a stroll through a city: they are both part of the way we seek out meaningful experiences of the world.

It may seem odd that, in all likelihood, Bentley Mays will mostly be remembered, not for his articles on art and architecture, but for two personal memoirs, In the Jaws of the Black Dogs: A Memoir of Depression (1995) and Power in the Blood: Land, Memory, and a Southern Family (1997). A profoundly religious man who had converted to Catholicism in the late 1990s after a vision at the Marion Shrine at Lourdes, France, Bentley Mays was always frank about the ways in which depression afflicted his life, and he understood depression less as a medical phenomenon then as an existential one: its main ingredient was desolation, a draining of meaning from experience. “I am a product of psychiatry and pharmacology, without them I could never have gone on,” he once told me, “but as time goes on, the medications stop working and a different one has to be found, and eventually nothing will work.”

Bentley mays knew that in the end the psychiatrists did not offer a cure but simply, and mercifully, held the black dogs at bay for a while, just as he understood that both religion and art and architecture allowed for an immediate and sometimes transcendent experience of meaning that was in the end a fragile reprieve and a gift. “[M]uch great art and architecture, contemporary or otherwise,” Bentley Mays wrote in In the Jaws of the Black Dogs, “has the power to slash through the cottony baffle quilted around my mind, and let in pleasures so acute as to be almost painful.” Part of Bentley Mays’s achievement, and the core of his remarkable courage and humility, was to remain open to those moments, and to enable others to see them as well.

The last time I ran into John Bentley Mays was a few months ago at an Orthodox Church in east Toronto, where he was speaking about religion and depression. He told me he was working on a novel about the early life of the iconic German artist Joseph Beuys; he apparently completed a draft of the novel days before his death. That Bentley Mays should be studying the early life of an artist like Joseph Beuys made a great deal of sense to me—just as it made sense to me that he was obsessively drawn to the music of Richard Wagner, especially the epic Ring Cycle, which he had seen performed many times and of which he owned countless recordings. Beuys returned from the Second World War shattered in mind, body, and spirit, having been shot down over the Crimea and mysteriously rescued and nursed back to health by Tatar tribesmen. Back home, Beuys contemplated becoming a religious man and ultimately turned to art in a way that was positively monastic; his early drawings and sculptures are inspired by both the early German church and the Italian Renaissance. In different ways, and on different scales, both Wagner and Beuys sought out overarching mythologies that would hold together the fragmentation of human life and offer immersive experiences of meaning.

In the end, Bentley Mays was too modest and pragmatic to think art offered a cure. I do think he believed it offered an eruption of the timeless into the affliction of ordinary life, or as he wrote, “an hour of twilight, touched both with the uncertainty of seeing and with the beauty of diffuse radiance that comes at day’s end.”