The faces of the dolls are as lovely as moulded vinyl can be. The shock of their price—Maplelea Girls sell for $100—wears off when you hold one of their eighteen-inch bodies in your hands. The quality is so apparent. The hair is thick, the hands lock, the eyes are sharp and vibrant, opening and shutting without that opiated, half-lidded look cheaper dolls sometimes endure in repose. The clothes and furnishings are equally beautiful. The doll named Saila Qilavvaq, an Inuit girl from Iqaluit, can be outfitted in a traditional hooded winter garment—an amautik—handmade in Nunavut and worth every nickel of $56.

Maplelea Girls are luxury toys, but also markers of consumer identity. Since 2003, Maplelea has sold about 100,000 dolls, along with half a million accessories, making it one of the most successful toy companies in Canada and among the fastest growing. Its success, given the limited market, is a surprise. “The goal of most Canadian toy companies is to sell into the United States because it’s ten times larger,” says Maplelea owner Kathryn Gallagher Morton from her office in Newmarket, Ontario. “To do that for just the Canadian market is a huge risk.”

The dolls have emerged amid deep confusion about what Canadian content represents. It’s a great time to scream, “I am Canadian,” but not a great time to ask what the adjective might mean. If you want to sell beer, you wave the flag. If you want to sell coffee, you explain that your coffee is really about hockey, even if Burger King owns you. Pride runs high. We howl through the streets, celebrating our victories, yet with a few notable exceptions Canadian cultural nationalism is dead. International conglomerates have bought nearly all the major publishers. Our music and film are mere addenda to the Hollywood entertainment machine. The CBC is being stripped for parts.

The question of identity is beset by piety and wishful thinking and institutional inertia and plain nostalgia, but Maplelea Girls are free of all that nonsense for the simple reason that they are a product. They represent the Canadianness that parents want to buy for their children, and the Canadianness that children want to be bought for them. They sell the Canadian identity that the market can bear.

There are many differences between Canada and the United States. July 1 and July 4. Maple syrup and corn syrup. The West, which America conquered, and the North, which is unconquerable. After a bear attack in the United States, the sympathy lies mostly with the human attacked; after a bear attack in Canada, the sympathy lies mostly with the bear. To this list of differences, we may add American Girl and Maplelea.

The American franchise has been in business for nearly thirty years and amounts to a craze, both here and in the US. American Girl has sold more than 25 million dolls and 147 million books since 1986; sales hit $633 million in 2013. Its website attracts 72 million visits a year. Its magazine’s circulation has surpassed 450,000. Barbie sales have dropped steadily since 2011: at five times the price, expensive dolls with stories are replacing the down-market plastic toys. (Mattel owns both Barbie and American Girl.)

In 2014, American Girl established retail spaces within Indigo stores in Toronto, Vancouver, and Ottawa. The boutique at the Yorkdale mall in Toronto was swarmed by 2,000 girls on opening day. Among market analysts, the rule of thumb is that Canada represents 10 percent of North American sales, which would translate to a staggering $60 million annually. (Maplelea sales are just under $5 million a year.)

There are forty combinations of eye, hair, and skin colour available in the My American Girl line alone. And there’s more: Bitty Babies and Bitty Twins, and dolls without hair for girls with cancer. The accessories are fantastic, too. An egg chair, straight out of a 1970s California bedroom, retails for $100. At American Girl stores, there are doll hospitals where you can have your doll repaired, or her ears pierced or fitted with hearing aids. There is a restaurant where you can eat with your doll beside you (the waiter poses riddles for you to solve together) and a photo studio where you can get your picture taken together.

Maplelea Girls are sold online, and by phone and mail-order catalogue, which makes them slightly less expensive than their American counterparts, although you can still send your Maplelea Girl to a “spa” to have her repaired. Maplelea is a bit more prudent, more restrained, less hasty, less needy of the miracles of product diversification. Like so much of Canadian culture, Maplelea is an American idea made slightly more virtuous.

Before she conceived of Maplelea, Morton ran Avonlea Traditions, which held toy licences for Anne of Green Gables and the RCMP. In the 1990s, the Canadian-identity business changed and Morton changed with it. “Maplelea is how we see ourselves as opposed to how others see us,” she says. She designed the Maplelea Girls over three years; the process involved exhaustive consultation with girls, parents, community groups, librarians, and specialty toy stores. This, according to the catalogue, is what they came up with:

Taryn, Brianne, Alexi, Léonie, Jenna and Saila are all very different—they like different hobbies, sports, school subjects, foods, colours and even have a different personal fashion style! However, there are some things that they have in common—they are all bright, caring, energetic Canadian girls who think Canada is one terrific country.

The first thing to notice: geography is everything. The original American Girl dolls, which comprised the BeForever line, were characters out of American history, often ones who’d lived through national crises: Kaya and her mare, Steps High, from 1764; Caroline Abbott from the War of 1812; Addy Walker, a runaway slave from 1864; Kit Kittredge, who survived the worst of the Great Depression. The Maplelea Girls were not involved in the March West nor, God forbid, the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. They weren’t watching quietly from the sidelines at the signing of Treaty Number Six. They emerge from the landscape instead.

Jenna is the Maritime doll. She loves to watch the gannets: “I live in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, right beside the Atlantic Ocean. I have fiery red hair and a personality to match.” Taryn is from Banff, which makes her technically Albertan, although spiritually she is closer to British Columbia: “Three things I couldn’t survive without are my hiking boots, clean fresh mountain air and butterflies. Can you tell I’m a bit of an environmentalist at heart? ” Brianne, from Manitoba, is a blond farm girl: “I love my Welsh pony named Chinook, belong to 4-H and dance in the big Ukrainian Festival in Dauphin every year.” Saila, the Inuit girl, eats grandma’s bannock and crowberry jam and travels immense distances by boat or by qamutik (that is, sled) for bouts of clam digging. There are two city girls: First there’s blond Léonie Belanger-Leblanc, from Quebec City, who plays “outdoor hockey whenever I can” and wears her Québécois pioneer outfit when she goes to visit her cousins at the cabane à sucre. (Naturally, the girl from Quebec has the best clothes.) Then there’s Alexi, the girl from Toronto, whose skin is a subtle, unidentifiable shade of brown, and who loves computers. Taryn and Léonie are the bestselling dolls in the series; they also have the most common eye- and hair-colour combinations in Canada, according to Maplelea.

These energetic girls fill the emptiness of the land with their hearts. It’s a century-old archetype, the girl who crowns herself with dandelions. Emily Pauline Johnson had the song her paddle sings. Susanna Moodie and Catharine Parr Traill fought the bush with all their love and contempt. Anne of Green Gables remained wilful in her imagination despite a childhood of indentured servitude. Maplelea, like all iconic Canadiana, reveals the oppression of the landscape and the human response to that oppression.

And then there is Alexi. Like the other girls, Alexi comes from a place, but a very specific place—not just a city or a province, but a neighbourhood. She is from Cabbagetown, in Toronto. “People come from all over the world to make Toronto their home. That makes me proud,” she writes in her journal. (Every Maplelea Girl comes with her own journal, and each item of clothing comes with new pages.) “Restaurants here are fabulous. Cambodian, Greek, Indian, Italian, Chinese, Caribbean—we have it all.” She visits the Royal Ontario Museum and the St. Lawrence Market, and Centre Island for family picnics. She plays piano and wants to be an inventor. Her mother, Emmay, manages IT for a big bank. “My dad, Ben, is an artist and he has a big sunny studio where he says the light is best. He’s a stay-at-home dad, and he’s always here when I get back from school. He’s a terrific cook and an outstanding housekeeper.”

With all this detail, one absence is glaring: her ethnicity. The images of her parents—Dad’s skin is light brown, Mom’s is darker—make it impossible to identify any ethnic origin. “We decided to not state what her ethnicity was or her cultural background,” Morton tells me. “The girl could make up that aspect herself.”

Alexi’s identity must be hidden for two reasons. The first is market based. She belongs to the category, so prevalent in advertising, known as “ethnically ambiguous.” The second is more subtle. The appeal of Alexi, like the appeal of Toronto, is in the impossibility of determining her ethnicity. To put a name on her would be to reduce her, to narrow the possibilities of her being.

In the rest of the world, the multicultural impulse—the belief that ethnic diversity is a public good to be celebrated in itself—has come under severe threat. European countries have seen the rise of anti-immigrant parties, from the UK Independence Party to neo-fascist groups in Greece and Hungary. Even Denmark and Sweden have seen dramatic spikes in explicit political xenophobia. Australia recently unveiled its No Way campaign, in which the phrase You will not make Australia home looms over an image of a stormy sea. They released the threat in seventeen languages. In Canada, there is no national anti-immigrant party with a significant voice. The Conservative party, or one of their former splinter parties, might once upon a time have wanted to ban turbans from the RCMP. Now visiting a Sikh temple is the equivalent of visiting a state fair during an American election—a required political ritual for all sides.

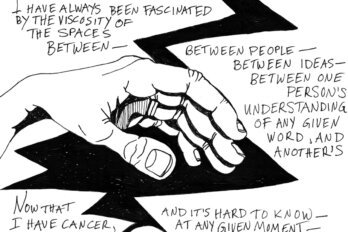

Canada, alone among the liberal democracies, has kept its idealism about immigration, mainly because its expectations are so low. Canadian culture, unlike French or even American culture, is not an ancient tradition whose symbols are internalized from birth. Immigrants to other countries integrate or fail to integrate into long-standing identities. Canadian multiculturalism demands tolerance and openness in the service of tolerance and openness. Hollowness haunts Canadian multiculturalism, although it can be a comfortable hollowness—the hollowness of a nest, perhaps.

The contradiction that Alexi represents is the contradiction of our future. She is ethnic with no ethnicity, a blending of anything with anything. We are mixing ourselves toward . . . who can say? The absence at the heart of Alexi is a horizon of limitless possibility, blank pages on which anything or nothing can be written.

Canada is a country that makes people feel small. That is its gift among nations. Human beings are small. It is good to be reminded of it. A 1980s archeological survey on Axel Heiberg Island, in what is now Nunavut, found among other Dorset artifacts an antler carving of two faces, one of which appears to be European. Not an archeological record of slaughter, as is so often found, but a 700-year-old miniature, the face of a little other. A record of an encounter between peoples, between cultures, on an unimaginably desolate strip of the earth, for the purposes of trade.

Dolls are our diminished idols, repositories of longing and fear we keep in children’s bedrooms. In this country that makes people feel small, the kids put their wild-hearted dolls to bed at night and wake them up in the morning. Even abandoned, the dolls who sleep or are tucked away or sit in empty rooms around little tables in frozen conversation don’t suffer from too little meaning. Dolls have everything that people have. They have names and stories and bodies and houses and people who love them. They have more than most people. They’re only missing life.

This appeared in the March 2015 issue.