In the closet of my room hangs a piece of woven fabric. Arrows of white, yellow, green, and blue split broad bands of red across three metres of wool. It is worn wrapped around the waist, and was once the most versatile garment some of my ancestors possessed. Its folds held hunting knives, pipes, and flint. It kept coats closed against prairie winters and goods wrapped and secure over a portage. Draped over a dead buffalo, it identified the owner of the kill. The Metis sash symbolized the nation that wore it—a mix of colours and races, neither European nor Indian.

Today, the Supreme Court of Canada hears Daniels v. Canada. The case is more than fifteen years in the making, named after Harry Daniels, a Metis leader who took the government to court because he wanted his people to have the same rights as the other Aboriginal groups included in Section 35 of the Constitution Act. Through the federal government, Inuit and First Nations receive health care, education, and the right to file land claims. But the federal government has always insisted that the Metis are not “status Indians,” and are therefore the responsibility of the provinces. When a ruling comes early next year, the Daniels case will finally decide whether the Metis are, in terms of our constitution, “Indians.” If the court sides with the Metis, it will potentially enfranchise 450,000 people who identify as such—1.4 percent of Canada’s population. But the case has brought up a deeper question: If the Metis are Indians, who are the Metis?

Two sides have emerged in the debate: those for whom aboriginal ancestry and a connection to the culture is sufficient, and those who believe that being Metis means being able to trace your genealogy back to the historic “Metis homelands” across Ontario and the West. Both sides are intervening in the Daniels case—trying to influence the judges’ decision in their favour. There are many things at stake: money for the organizations that claim to represent the interests of Metis, benefits for the Metis themselves, and, fundamentally, who is in and who is out.

The Métis Nation of Ontario head office is in Ottawa, in a strip mall across from a francophone high school. It’s not the only organization in Ontario that claims to represent the Metis, but it’s the largest and best organized. There are MNO offices in twenty-one communities, with more than 18,000 registered citizens working to deliver education, health, and economic development programs throughout the province.

The MNO is a member of the Metis National Council, an umbrella organization composed of Metis governments (provincial bodies made up of and elected by Metis people) from Ontario, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and BC. In 2002, the council did something deeply divisive: it tried to define who the Metis were. What the MNC came up with has helped advance Metis rights provincially and nationally, but it has also excluded many people who long considered themselves Metis.

Gary Lipinski is the MNO’s current president and CEO. He wears his salt-and-pepper hair long and spends much of his spare time on the land, and has helped oversee the organization’s transition over twenty-two years from a loose coalition of disaffected people with aboriginal ancestry to a well-run structure that represents the interests of Metis citizens throughout Ontario.

The term “citizen” is important. When I worked in the MNO’s registry department, we would sometimes field phone calls from anxious applicants asking about their Metis status card. They were gently reminded that they had, in fact, applied for citizenship within the MNO. It’s an important distinction: Despite being included in the constitution as an Aboriginal people, the Metis do not have any of the benefits associated with Indian status, from tax breaks to education to health care. “I still get people calling me, very emotional,” says Lipinski. “They say, ‘What do I do? My daughter’s been accepted to university, but I can’t afford it. My ancestry’s such that I could qualify for Indian status but I’m not First Nations. Yet if I register as an Indian, then my daughter’s tuition is paid for.’ So how is that just, that people have to pretend to be another identity in order to succeed in school?”

Describing my heritage to people often turns a history lesson into a math class: suddenly, it’s all about fractions. My grandmother is a Metis elder from Alberta, so, assuming that she is half-Cree and half-French, that makes me one-sixteenth Cree. The historical antecedent of this kind of thinking goes back to one of the first English terms for the people: half-breed. Even one of the Cree terms, âpihtawikosisân, means “half-people.” The question remains to this day: When—and where—did the Metis stop being part-something and become fully, distinctly Metis?

“That’s the million-dollar question,” says Brenda Macdougall, the chair in Metis Research at the University of Ottawa. Many scholars, she says, view the Red River as the birthplace of the Metis nation and as the fulcrum of conflict. Over years of settlement, this broadly defined region produced a distinct people who eventually rose up to defend their land. “But that doesn’t preclude that there are Metis communities or populations that are emerging elsewhere at the same time,” says Macdougall. “The way Metis history has been written is in an east–west trajectory, like Canadian history more generally: you start in the east and you move your way west as fur traders and settlers.”

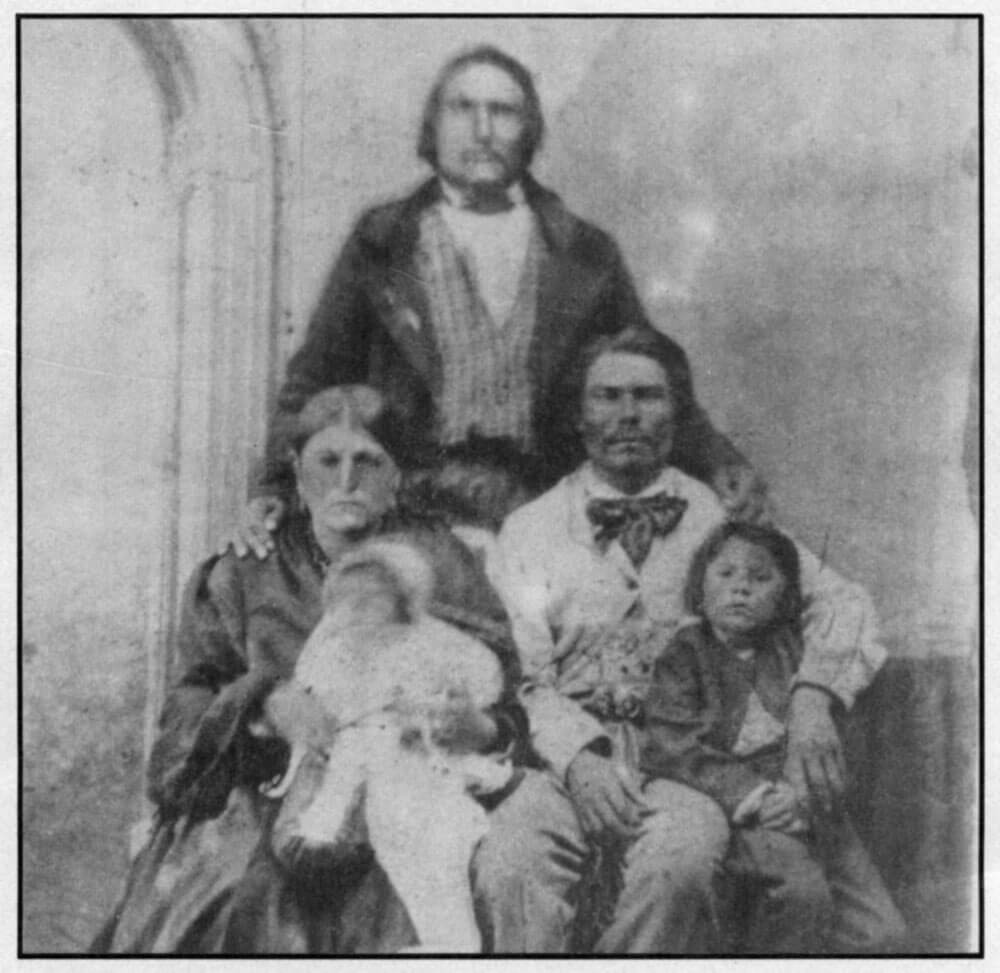

My most prominent Metis ancestor, Abraham Salois, was born in 1830 at Fort Edmonton. He hunted buffalo prolifically, said to have once killed about thirty in a single run. He traded across the West, and was fluent in a number of First Nations languages, including the hand signs Plains people used to communicate if they could not understand one another’s spoken language. His life is well documented, and I would satisfy the genealogical requirements for citizenship within the MNC’s guidelines. But there are a growing number of people who contend that you don’t have to be from the West to be Metis.

In October 1993, just outside Sault Ste. Marie, father and son Steve and Roddy Powley shot a bull moose without a licence. They left a Metis card and a note pinned to the animal’s ear: “Harvesting my meat for the winter.” Conservation officers deemed the kill poaching. It was the first significant test case for Metis constitutional rights. Ten years later, in R v. Powley, the Supreme Court affirmed that the Metis could exercise their traditional rights to hunt—provided that they self-identified as Metis, had an ancestral connection to the Metis community, and were accepted by the contemporary community. Jean Teillet, the Powley’s head counsel and great-grandniece of Louis Riel, suggested these guidelines, which were based on the “national definition” of Metis that the MNC had adopted in 2002. After the ruling, the MNO and other council members turned these guidelines into a registry process that would decide who was in and who was out. Rights were now inextricably tied to identity.

Among those who consider themselves Metis, Teillet is a polarizing figure. In a 2012 address to the Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, she articulated a controversial vision of the Metis nation: “I would say that there are a lot of things that Metis are not. They are not the reject pile where you throw all of the people who lost their Indian status. We are not a garbage can, and we are not the leftovers. We are not where you go if you cannot sign up with someone else.” It was inflammatory rhetoric, predicated on the idea of a historic, distinct Metis group that excludes much of central and eastern Canada, as well as BC.

It has certainly inflamed Karole Dumont-Beckett, the registrar and a founding member of the Métis Federation of Canada that was founded “to represent all Métis from all regions of Canada,” and an intervener in the Daniels case. The federation opposes the MNC’s narrow definition, arguing that Metis communities exist from sea to sea. Dumont-Beckett has Metis ancestors from all across Canada, she says, and doesn’t want to see her family members alienated from an identity they’ve always held. Although she can trace her genealogy back to Red River, she resents the idea that the Metis arose in the West, and accuses contemporary scholarship of working to “systematically eliminate” the idea that Metis people existed outside of western Canada.

For his part, Lipinski has no problem with the definition as it is. Embroiled in the Powley case, he says, “There was legitimate concern that if we didn’t develop our own definition then the courts would do it for us.” MNO’s registry system also lends it credibility and legitimacy when dealing with the government. Digitized and instantly searchable, each file clearly states how that person is connected to a Metis (not First Nations) ancestor from the “historic homeland.”

Of the many misconceptions Metis people have about the Daniels case, perhaps the greatest is that it will solve the intractable problems surrounding rights and identity. The MNO has seen a spike in applications every time the case hits the news; people have been calling the office and wondering when they’ll receive their tax cards. But if the Supreme Court does rule in favour of the Metis, it will still be a long time before any agreements with the government are reached. The fifteen years it has taken to conclude the case does not bode well for future negotiations. So despite the grave warnings in some newspapers, the change will not immediately create a leisured class of Metis coasting on education, health, and tax benefits. It also won’t define them—but it will make the need for a definition more important than ever.

The fundamental problem is that definitions are always exclusionary. They may be so inclusive as to be meaningless, or so exclusive that they alienate a significant number of the people you wanted to represent. “Somebody’s always going to be left out,” says Macdougall. “That functionally creates this ‘non-something’ category again. It hasn’t gone away. The reality is, some people are going to be left out, and quite frankly, they are going to be our family members.” It’s a dark reminder of the nineteenth century, when scrip (land given to individual Metis by the government on a case-by-case basis) and treaties legally severed groups and families that thought they were related.

These kinds of divisional identity politics play into the federal government’s hands. Before the Metis were included as an Aboriginal people in the constitution, Metis and non-status Indians were allies. A political movement arose in the West based on a mutual sense of historic injustice. This worked for decades—until Metis rights and rights for non-status Indians became separate issues. Since then, “The outcome has been that we—all of us—have stopped seeing each other as relatives,” says Macdougall, “We see each other as competition.”

There is only so much money available, according to the government, and each Aboriginal group is forced to compete for their portion. “It encourages this sense that we’re not related,” says Macdougall, “and we spend more time arguing with each other about the authenticity of our identities than we do dealing with the federal government, that has already set up this structure that none of us can win in.”

The conversation around Metis identity is necessarily informed by history, but it is worth considering what happens next. In some ways, no matter how whole we become, the Metis are fated to be a liminal people—caught between two sides, extending one way, then the other. Maybe the sash weavers knew that. When I take mine out from time to time, and wrap it around my waist, I marvel at the patterned arrows racing across its length; and for a moment, it feels like they are travelling between an indeterminate past and an unknown future.