Most novelists who are fortunate enough to have had their novels translated into other languages are also fortunate that they are unable to read those languages. I have a closet ful of translations of my books, but no one who can read a language other than English has ever seen the inside of it, and no such person ever will.

It was once my fondest wish to be “translated.” (That is how people speak of it, as if it is the author and not the books that are translated. “How many languages have you been translated into? ” I have been asked, and have been told by agents that “I” would soon be “appearing” in some foreign country.

There is no resisting the images this conceit brings to mind: the sudden, startling, end-of-the-world-heralding apparition of me on a streetcar in Bucharest, or my face being mistaken for some saint’s as it takes shape in an oil stain left by a Volvo on the wet pavement in Cracow.) I am glad to have been translated, but whenever I think of the word “translation,” it is attended by the sobering thought that you should be careful what you wish for.

The first of my books to be translated was The Colony of Unrequited Dreams. “We have sold you into Germany,” my agent e-mailed me. More unbidden images, perhaps all the more vivid because “Germany” scans like “slavery.”

My first contact with a translator occurred at three in the morning. It was a fax from my three translators in Germany, where it was already late morning. (It was only partly because of the book’s length that three were needed, I was told. There was some satirical verse in Colony, which no mere translator of prose could be trusted with, and so a poet had been hired. There was also the “problem” of literary irony, always a tricky one for translators. Thus, an “ironist” had been hired. The poet and the ironist would collaborate with the translator of the “more straightforward balance” of the book.)

The fax from my trinity of translators read: “Dear Mr. Johnston. We have many questions arousing from your book.”

This declaration would, in any context, be off-putting. Coming from not one but three translators, it seemed ominous. Even as I was replying, I was trying to remember how often I had used the word “arising” in Colony. “I think,” I faxed back, “that you mean ‘arising,’ not ‘arousing.’ ”

There was a long delay before the next fax came. It read: “Dear Mr. Johnston. We hope you will be not dismayed by the inauspicious inauguration of our relationship.” Wondering what the German word for thesaurus was, I wrote back that I was not dismayed. Reply: “This is good to our ears, as we very much admire The Territory of Unrelenting Nightmares.” I replied: “You seem to have translated the title of my book rather too literally into German and then back again into an English title, which is not the same as the actual English one.” Another long delay.

Our exchange continued in this manner for weeks. The trio sent me such queries as: “Dear Mr. Johnston. You refer to resettled communities in your novel. May we assume that these communities are concentration camps? ” You may do so, I felt like replying, but only if you agree not to pursue translation even as a hobby in the future. The queries, with their treacherous ambiguities, kept coming. An interesting exchange took place as I tried to explain that a passage called “Hooligans Seized Her” was a parody of a scene from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. The ironist-translator complained that his powers had never been so taxed, to which I replied, in the cheerful certainty of being misunderstood, that the same could be said of my patience. The ironist replied by asking how, despite being a doctor, Ihad found time to write such a “complicated” book. “You see,” he said in a later fax, “I too can amuse myself with puns.”

When my author’s copies came, I was not surprised to see that the cover was an abstract depiction of extreme Teutonic gloom that bore the title Die Kolonie der unerfüllten Träume. That the German word for “dream” closely resembled the English “trauma” explained much of what had transpired between me and my translators, and, for me, added to the works of Sigmund Freud a note of whimsy that other people tell me they are unable to detect.

Other translations of Colony followed. The Dutch publishers decided that they could make do with just two translators, one for the prose and one for the “poetry.” But they also decided that it was necessary that these translators be sent to St. John’s, where they discovered, to their surprise, that I had not lived for almost a decade. Consultations with the author were “cancelled” and a three-week, all-expenses-paid tour of the novel’s setting was judged a suitable substitute. Soon, my phone and fax were ringing at intervals throughout the night, the heavily accented phone voices of two Dutch women now surreally residing in St. John’s, full of remote morning cheer, asking me questions about the weather in idiosyncratic English. “I know for certain that it’s dark,” I said. “It always is in Toronto at this time.” I was informed that, in Newfoundland, where I had lived for a quarter of a century, “the weather is of paramount importance.” Otherwise, I asked them, how was their “research” progressing?

“We have found Sheilagh Fielding,” one of the women said. I assumed that she meant that, from staying in St. John’s, they had “found” the essence of the main, non-historical character in Colony.

“That’s wonderful,” I said.

“We found her in a bar called The Ship Inn,” the poet-translator said. “She was sitting by herself just as we expected. She is just as you describe her in your book.”

I began to explain that Fielding was entirely fictional and that, even if she were real, it was unlikely that she would be frequenting bars, as she would recently have celebrated her one hundred and first birthday. Also, trying to imagine whom they had “discovered,” I expressed my hope that they had not introduced themselves to her.

“Oh no, we would never speak to Fielding,” the woman said. “She has such a sharp tongue.”

“In the book, yes,” I said, “but she doesn’t actually-”

“We both agree that you didn’t entirely do justice to her face.”

“But you will not change my description of her, will you? ” I said.

In the end, they agreed, reluctantly, that their Fielding would conform, “as much as language will allow,” to mine.

When the Dutch copies came to my door, I hid them in my closet, too.

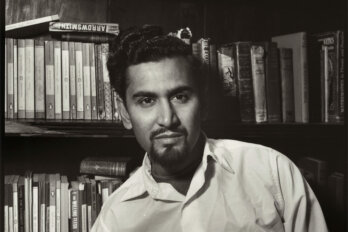

Not long after my memoir, Baltimore’s Mansion, was translated into German as The Fatherland, I had dinner in Washington with a friend of mine, the American writer Howard Norman, whose National Book Award-nominated novel The Bird Artist is also set in Newfoundland. I was telling him of my misadventures in translation when he interrupted me. “I assure you,” he said, “that nothing you could tell me will come close to this.”

He said The Bird Artist had recently been translated into Japanese. Copies of the translation had been delivered to Howard’s house and he, being unable to read the language, had admired them briefly and set them aside.

Six weeks later, his Japanese translator telephoned to ask him how he liked the book.

“Well,” Howard said, “I haven’t actually read it, but it looks wonderful.”

“Oh,” the translator said, voice quavering.

“Is something wrong? ” Howard asked.

After a long pause, the translator explained.

“Well, you see, Howard, I made some changes to your book.”

“What sort of changes? ”

“I added some things.”

“Such as? ”

“Howard, in Japan, we have found that, if a book does not have sex scenes, it will not sell. So I wrote some sex scenes for you.”

He went on to explain that he had inserted into The Bird Artist—a book of minimalism in which objects are rarely described with more than one adjective and in which there is nothing more sexually explicit than a brief kiss—half a dozen graphically detailed sex scenes, the chief player in which was Howard’s main character, a shy, reclusive, wood-carving lighthouse keeper from Edwardian-era Witless Bay, Newfoundland.

Howard confirmed the translator’s story by taking the book to a professor of Japanese at Georgetown University. Howard described the sex scenes to me as extraordinarily precise, unambiguously gratuitous, and entirely superfluous to any aspect of his book.

“Six sex scenes,” he said. “They increased the length of the book by about one third.”

As of the writing of this piece, I have not yet been sold into Japan.