Ifirst encountered the photographs on this screen while researching From the Forest to the Sea: Emily Carr in British Columbia, an exhibition I organized with Ian Dejardin, director of the Dulwich Picture Gallery, in London. (It opens at the Art Gallery of Ontario on April 11.) Born in 1871, Carr lived until 1945, and during that time the forced assimilation of Indigenous peoples was proceeding full throttle. In the decade preceding Carr’s birth, smallpox had devastated British Columbia, with government officials having done little to stem the epidemic. About half the Aboriginal population perished; the death toll reached as high as 90 percent in the north. By the 1870s, the Canadian government had implemented an aggressive program of forced cultural assimilation. Children were taken from their families and communities, and institutionalized in residential schools. Malnutrition, along with physical and emotional abuse, was commonplace. At the same time, an influx of missionaries and anthropologists stripped Native communities of ancestral regalia and feast vessels, rattles and amulets, and, of course, totem poles, which came to reside far away in the museums of North America and Europe, where most remain to this day.

In 1884, the ban on the potlatch ceremony struck an additional blow, crippling an important mechanism for the consolidation of community and identity, and for the transmission of knowledge, property, and clan entitlements. Finally, as the twentieth century dawned, the landscape was increasingly ravaged by industrial logging practices. No longer was the natural world honoured as the seat of identity and spiritual connection, as it had been for millennia. Rather, it was aggressively reframed as a commodity, with Indigenous people struggling to find an equitable footing within the new economy. That struggle continues today.

Some of the pictures I encountered in my research left a deep mark on me, and I share them here with a sense of inquiry, sadness, and, at times, incredulity.

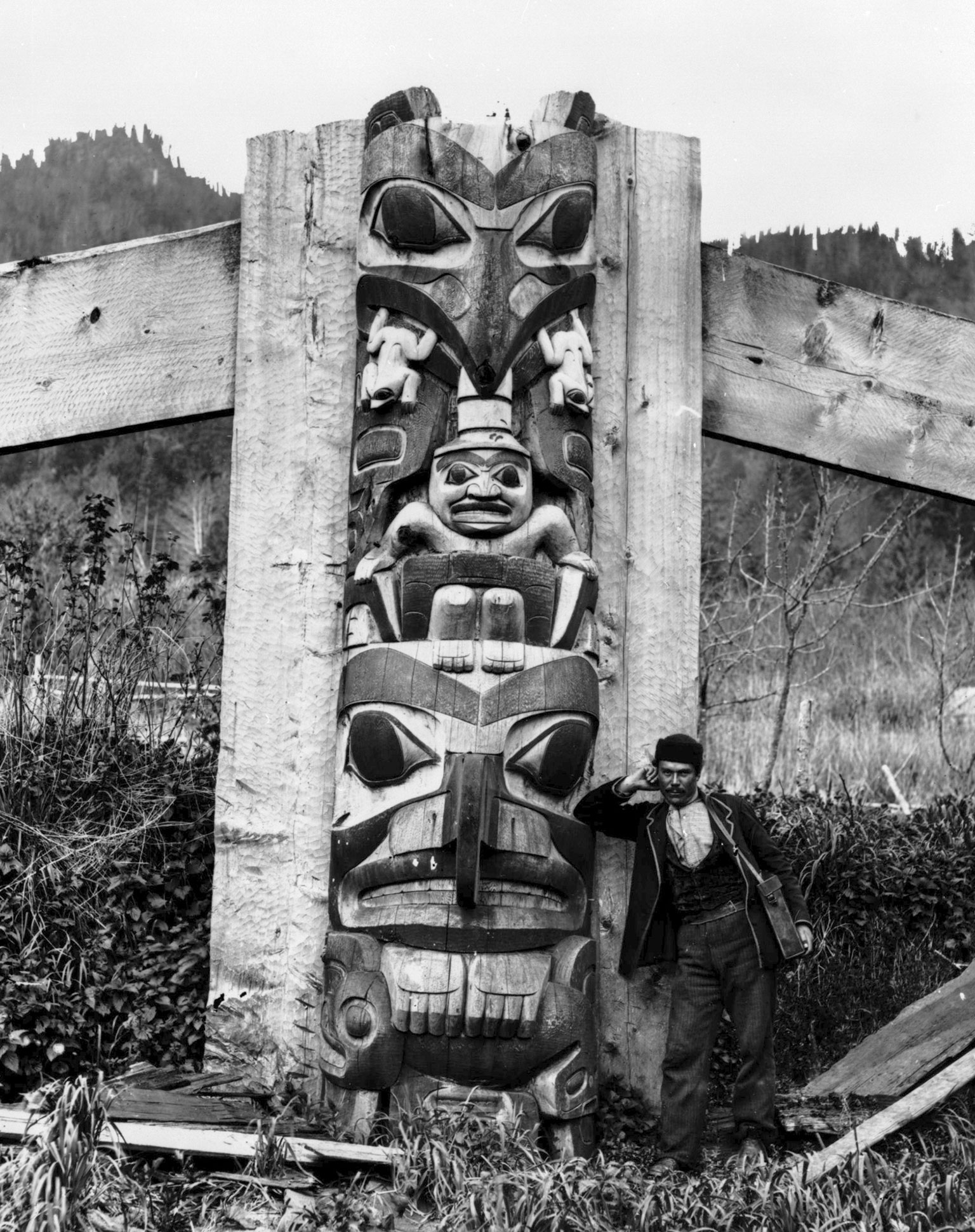

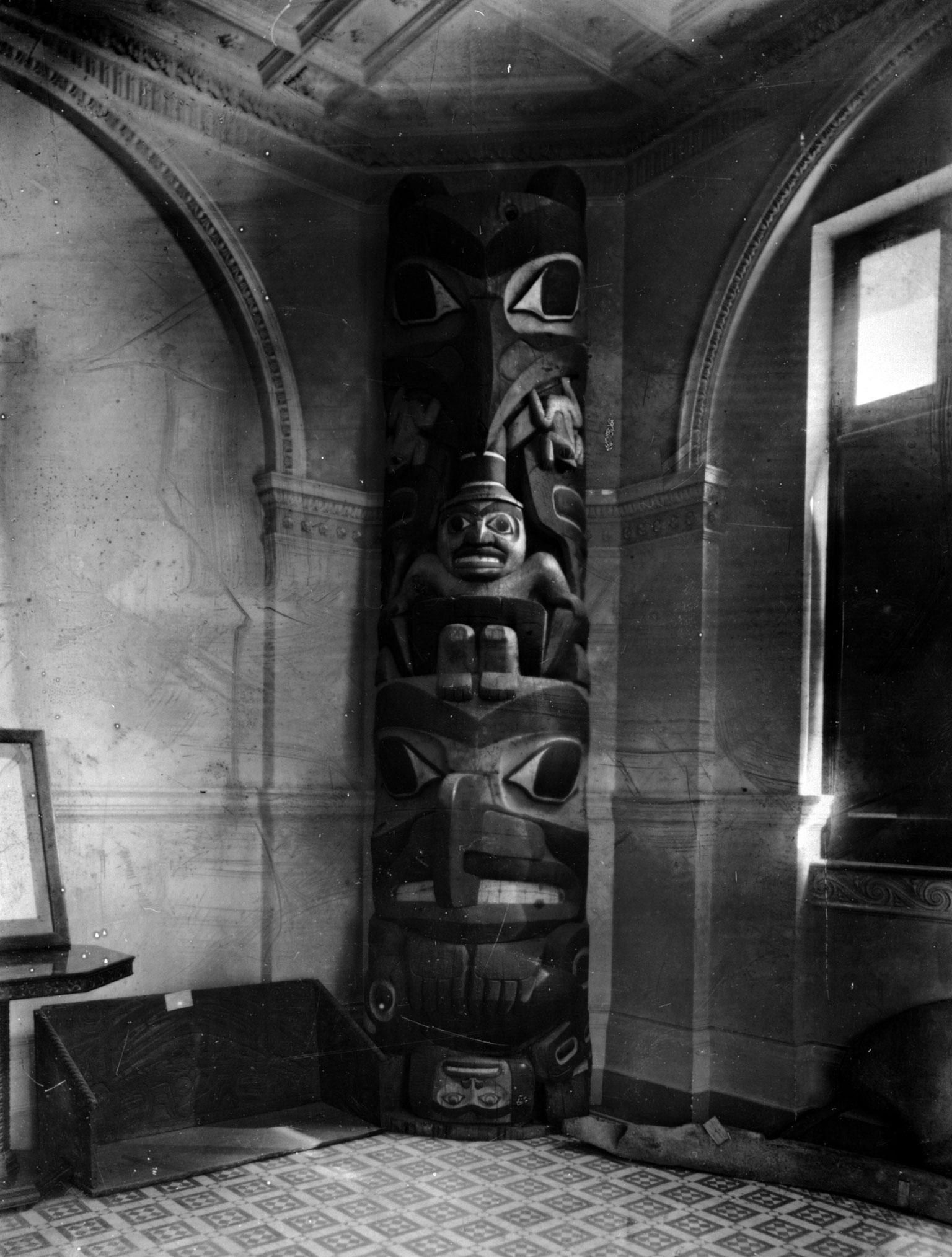

Polar Opposites In the image at top, a pole sits amid the grasses at Skidegate, exerting its authority as an anchoring presence. It speaks of belonging, and is materially of a piece with its natural surroundings. In the photograph below, taken around 1909, the same pole stands displaced in the British Columbia Parliament Buildings, in Victoria. A handsome monumental carving, it is now enjoyed primarily for its aesthetic sophistication.[/caption]

Courtesy of Jean-Luc Mercié

Courtesy of Jean-Luc Mercié

Surreal Life Following the seizure at Village Island, William Halliday displayed and photographed banned potlatch items at the Anglican parish hall in Alert Bay (bottom). They were then spirited away to museums in Eastern Canada or sold to American collectors. Halliday also sent twenty-two Kwakwaka’wakw men and women to Oakalla Prison, in Burnaby, for defying the potlatch prohibition. Others were forced to forswear their entitlements.

In 1980, Dan Cranmer’s daughter, Gloria Cranmer Webster, established the U’mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay, which worked to repatriate the objects. Ironically, the critical evidence she deployed in her efforts was Halliday’s incriminating suite of photographs. The mask at the image’s far left eventually found its way into the collection of the French surrealist André Breton; it sat on his writing desk in Paris (top). His daughter returned it to Alert Bay in 2003.

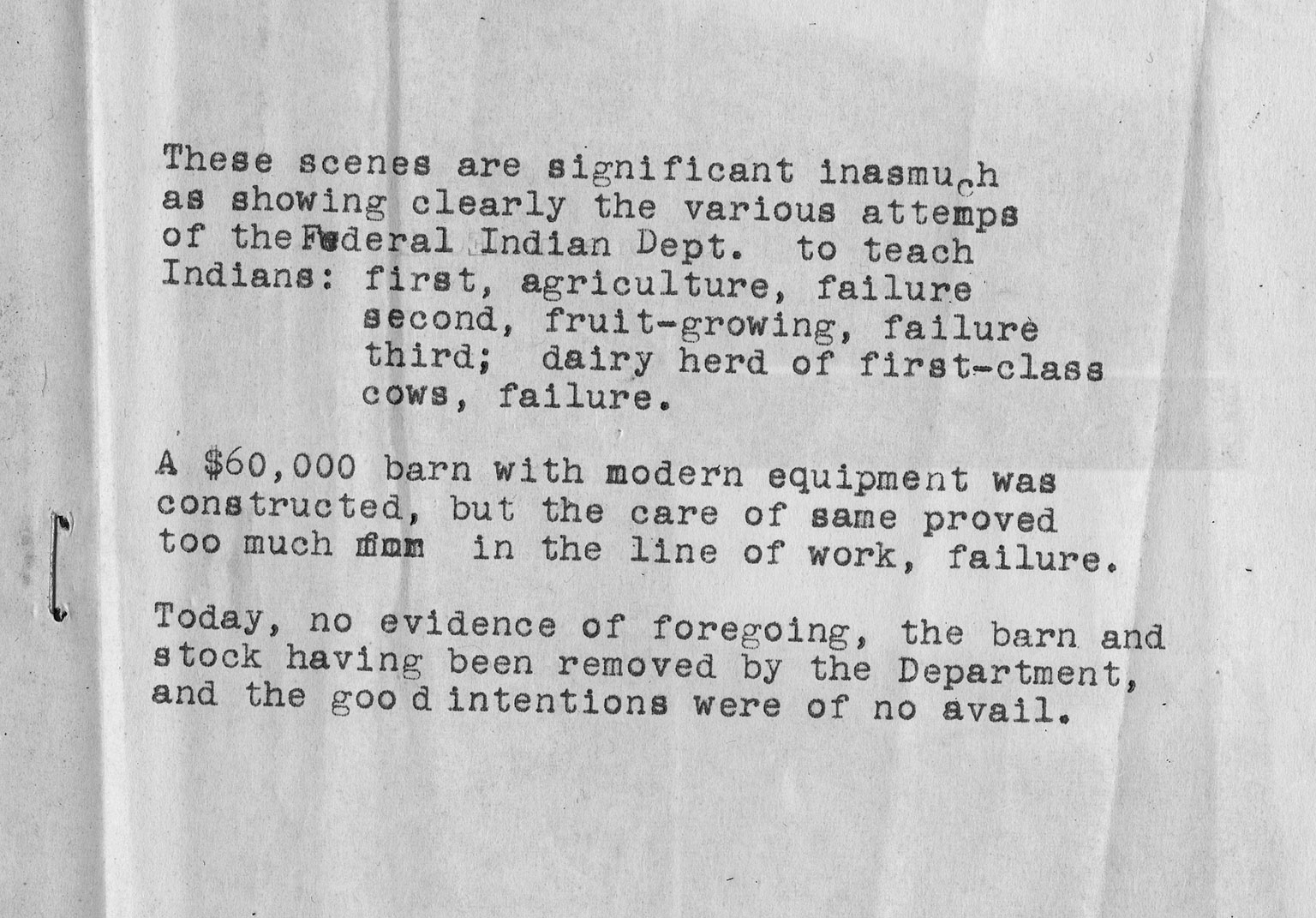

Images courtesy of the Audrey & Harry Hawthorn Library & Archives/UBC Museum of Anthropology Stunted Growth Students at St. Michael’s Residential School, in Alert Bay, worked long hours in the vegetable gardens and at various janitorial duties. James Barclay “Barney” Williams, a magistrate, kept a photo album while living in the area. He annotated several of his pictures with typed captions, some of which reveal his sense of racial entitlement and superiority. Here, for example, he mulls over the “failure” of the residential school students to embrace the tasks allotted to them.

Images courtesy of the Audrey & Harry Hawthorn Library & Archives/UBC Museum of Anthropology Stunted Growth Students at St. Michael’s Residential School, in Alert Bay, worked long hours in the vegetable gardens and at various janitorial duties. James Barclay “Barney” Williams, a magistrate, kept a photo album while living in the area. He annotated several of his pictures with typed captions, some of which reveal his sense of racial entitlement and superiority. Here, for example, he mulls over the “failure” of the residential school students to embrace the tasks allotted to them.

Ice Queen Williams’s album also documents Miss Canada’s visit to Alert Bay, where she bestowed her attention on the local schoolchildren around 1940. Her glittering whiteness and her Brittania costume confer upon her an air of frigid authority as the community children line up to pay their respects.

Naked State Like residential school students throughout Canada, the children of St. Michael’s were stripped of language, home, and parental love. On this occasion, they are literally stripped and exposed, forced to enact a racist caricature of their own identity. This photograph comes from the U’mista Cultural Centre, located next to the large, weather-beaten school, which was recently demolished.

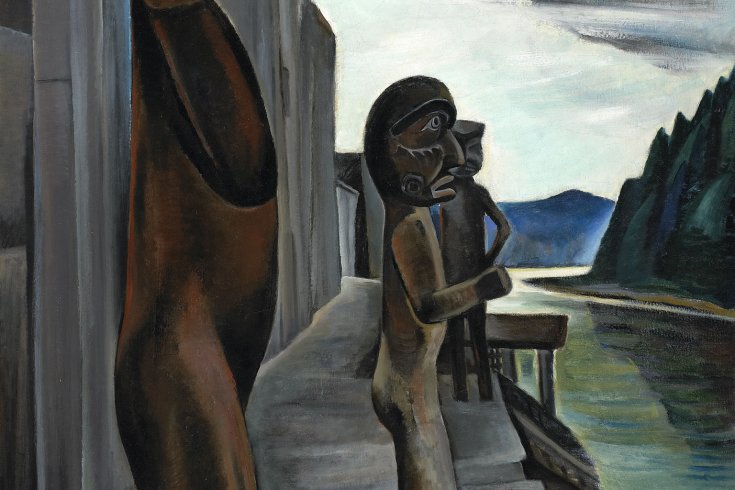

Deleted Scenes Blunden Harbour is one of Carr’s most curious works, in that it depicts a place she never visited. The painting is based on a 1901 photograph taken by the amateur anthropologist Charles Newcombe, but Carr deviated from the original image in several telling ways. The skies are gloomier, the tonalities more melancholy, and the Indigenous locals, engaged in their bustling quayside tasks, are erased, leaving only silence. Carr is a controversial figure in some quarters, as some of her work seems to find a kind of delectation in such disconsolate scenes. Blunden Harbour reflects the stylistic influence of Lawren Harris, her mentor; and also perhaps the sensational, even elegiac accounts of Indigenous peoples as a dying race that were popular in eastern Canadian cultural circles at that time.

This appeared in the May 2015 issue.