When I heard that Newfoundland would be the only province in Canada to introduce a tax on books—and that the government plans to close fifty-one libraries—I felt the sting of angry tears. I wanted to beg the government to reconsider. But they have dug in their heels.

Dale Kirby, the province’s Liberal minister of education, said in a recent CBC interview that the libraries scheduled to close have been open an average of just eighteen hours a week. He grumbled something about digital technology and the Internet being the real tools required to fight illiteracy. (Apparently books aren’t as essential to literacy as Kirby thought in 2012, when, in an interview on the St. John’s radio station VOCM, he called for renewed investment in libraries across the province, noting that libraries have digital resources as well as valuable hard copies, and that librarians are “great guides” to information. He also criticized the former Conservative government for cutting $100,000 from the library system.)

The tax on books and the closure of libraries is an attack on writers, bookstore owners, publishers, and students (who are being hit by this budget six ways to Sunday, through school closures, deep cuts to the university, threats to the tuition freeze, the loss of grants, job losses in the community colleges, and a hike in the price of already-expensive textbooks). Because of the tax, local publishers will doubtless be compelled to take fewer risks when they come across daring and innovative manuscripts by upstart writers. That means there will be fewer local books, fewer local stories, that see the light of day. It means a generation of young writers will not feel encouraged to write. And because of the library cuts, many in the province—especially those in rural areas—will lose basic Internet access.

There will be, without a doubt, a rise in illiteracy. Perhaps not in the traditional sense—although Newfoundland does already have one of the lowest literacy rates in Canada. No, illiteracy describes more than just the inability to read or write. Illiteracy takes hold when a culture is cut off from its stories, its history, its folklore. It takes hold when a generation of readers doesn’t get to see its experience reflected in literature, when a generation of writers has no access to publication.

As Kirby himself knows, librarians are information specialists. They carve paths through the rough terrain of the Internet. They make connections for us, synaptic, logical, and intuitive. They leap and dip through subjects, creating links. They say: there’s this and this and this. You may also want this. And soon they have thrust you into unknown territory, territory you have longed to see although you didn’t have a name for it. Librarians guide us deftly through centuries past as through breaking news; they guide us through novels, poetry, and folklore, through stories true and imagined.

Librarians are curators, too. They choose the books on library shelves for particular audiences. In a small library on Bell Island, Newfoundland, I might find a book about Bell Island, Newfoundland. I might read about the old mines, and then wander past the boarded up entrance of a mine and know it in a new way.

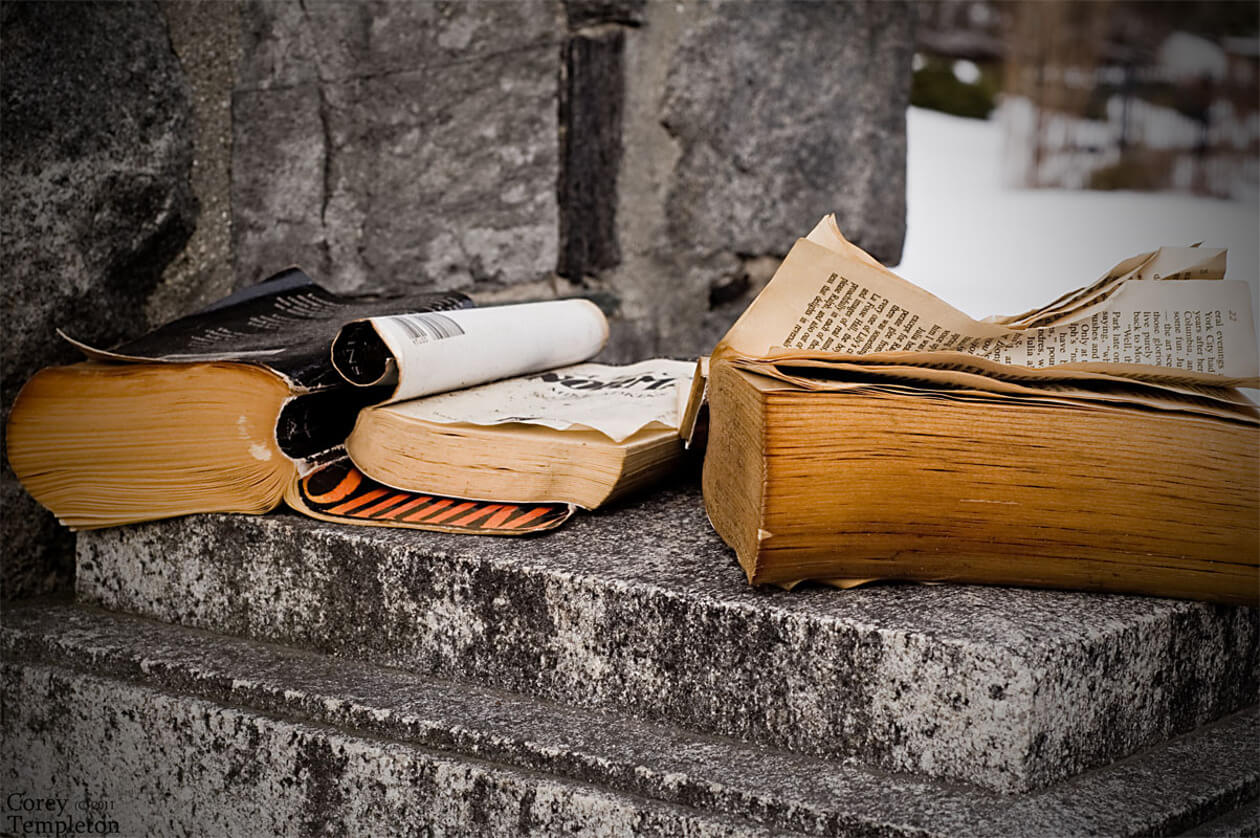

There’s little to Kirby’s suggestion that the Internet can take over the heavy lifting from the antiquated technology of the book: in a library you are surrounded by books you can hold in your hand. It is a sensual experience, the kind you can’t get online. The senses engage the imagination and trigger the memory. The cellophane covers of library books, the old ones that still have the card in the back, stamped with the dates of all the readers who came before, pages that have yellowed, paragraphs underlined in pencil, marginalia—some things can’t be Googled.

And libraries give us public spaces in our communities. They encourage loitering—and it’s in loitering that dreaming happens, that communal ties are formed. Maybe through screening a National Film Board documentary. Maybe with visiting authors. Maybe during story time with a circle of children sitting on the carpet, and someone reading aloud.

This government has not considered what it is that keeps people in Newfoundland—why Newfoundlanders feel an overwhelming pride in their province, despite its perpetual financial difficulties. It is a pride in a wealth of stories, in a rich culture.