Chief Wahoo has found himself at the centre of a legal controversy. His cartoonish red face, toothy smile, and feathered headband represent baseball’s Cleveland Indians—and, some argue, a particularly pernicious form of institutionalized racism. Last week, Douglas Cardinal, an activist, residential school survivor, and one of Canada’s most famous architects, filed an injunction against the Cleveland Indians, hoping to prevent their name and logo from appearing in Ontario as Cleveland faces the Toronto Blue Jays tonight. Today, a judge dismissed his application. But can—and should—a logo or name be banned because it’s racist?

Cleveland is the latest target of calls to change its racist ways, but it is not the first. The NFL’s Washington Redskins, for example, have clung obstinately to their title despite protests, citing their noble eight-decade history and how the name represents, among other things, “respect.” The Kansas City Chiefs, on the other hand, politely retired the worst aspects of “Warpaint,” a pinto horse ridden by a white man wearing a headdress. (A new horse parades around the stadium with a cheerleader.) Closer to home, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, an organization that represents Canada’s Inuit, has called on the CFL’s Edmonton Eskimos to change their name.

When these appeals fail, it’s sometimes left to the courts or the government to decide. In the United States, there is a law that prevents the registration of “scandalous, immoral, or disparaging marks,” applied at the discretion of the Patent and Trademark Office. Its policing has resulted in the failure to register, among other names, “AmishHomo,” “Mormon Whiskey,” and “Abort the Republicans.” Two years ago, the office cancelled “Redskins” as a registered trademark. But the law could soon change: at the end of last month, the US Supreme Court agreed to hear a case about whether the law violates the First Amendment right to free speech. The case revolves around whether Asian American musician Simon Tam can register the name of his band, “The Slants”; Tam argues that his band is reclaiming a slur in a way other marginalized communities have done. However, the court’s decision on the “Slants” case will probably also decide what happens to the Redskins trademark.

According to the patent and intellectual property law firm Smart & Biggar/Fetherstonhaugh, Canada has a law similar to that of the US: the Trademarks Act includes a section that prevents the registration of “scandalous, obscene, or immoral” marks. But as one might expect, there are fewer cases on the books. One of them dates back to 1992, when, despite objections, the Federal Court allowed the registration of the “Miss Nude Universe” trademark. Nude, it decided, was a “perfectly acceptable adjective.” As for the Canadian Trademarks Office, it’s inconsistently applied its own rules. Despite allowing the name “Fat Bastard” for a brand of wine, it refused to register “Lucky Bastard” for a line of spirits, forcing the conclusion that immorality depends on precisely what kind of a bastard you are.

Absent of much precedent, the Canadian Intellectual Property Office has put forward some guidelines, including this: “A scandalous word or design is one which is offensive to the public or individual sense of propriety or morality, or is a slur on nationality and is generally regarded as offensive. It is generally defined as causing general outrage or indignation.”

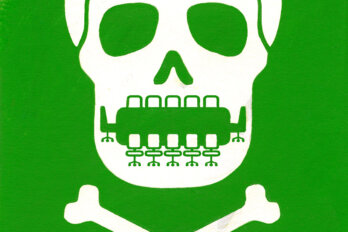

That description—”generally regarded as offensive”—provides an insight into what is perhaps the key takeaway from today’s decision. The most important battle takes place in the court of public opinion, and it takes actions like Cardinal’s to spur that discussion, whether or not they’re successful. Every time an Indigenous person reminds us that, yes, Chief Wahoo is a racial caricature, it’s an opportunity for education. And the more that we as a society come to understand that these terms and logos are offensive, the less defensible they become. In time, perhaps even the onus of responsibility will shift to its true centre: it’s not names and logos that are racist. We are.