The young palliative-care doctor, a nice Jewish guy in glasses, prodded around my grandmother’s stomach and explained that the swelling wasn’t only a result of fluid. Some of it was disease. Disease had now infiltrated her kidneys and pancreas. He said that it was a very horrible disease, this disease, but everybody in the room—except my grandmother—already knew approximately how horrible it was. My grandmother said tank you to the doctor and repeated the word hoff several times. Her English wasn’t very good and I didn’t think the doctor’s Yiddish was good enough to understand that the word she incanted meant hope.

Outside, in the hall, the doctor said that it was useless for me to wait around. It could be a month or it could be less, but there was no sense in me cancelling my plane ticket. I thanked him and then returned to the living room to watch the second period of the hockey game. In the other room, I could hear my mother and aunt lying to my grandmother about what the doctor had said.

The same summer we were given the diagnosis, I had gone to the induction ceremony at the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, New York. This is where I was told to check in with Charley Davis, who was recovering from a stroke but still lived independently in his house in San Francisco. Not that anybody knew very much, they said, but if there was anyone who knew anything about Joe Choynski, that person would be Charley Davis.

Joe Choynski was being inducted into the Old Timers’ category that day. Chrysanthemum Joe, Little Joe, The Professor, The California Terror: he was known as the greatest heavyweight never to win a title by the handful of people who still remembered that he’d ever been around. He was America’s first great fighting Jew. He quoted Shakespeare in his correspondence. He was a friend to Negroes. Coolies on the San Francisco docks taught him to toughen his fists in pickle vats, which was why he never so much as chipped a bone—bare knuckle or gloved. Legend had it that he also invented the left hook.

From Los Angeles, I called to find out that my grandmother hadn’t had a proper stool in three days and that the enema produced only an insignificant pellet which took her an hour to pass. Afterwards, in her exhaustion, she wasn’t able to leave the bedroom until morning. I was told that my grandmother’s dentures—which I had personally dropped off before leaving town—could not be repaired and needed to be replaced, and that my aunt had agreed to pay whatever it cost since neither she nor anyone else was prepared to tell my grandmother that she wouldn’t be needing new teeth.

My aunt asked exactly where this God is, especially since my grandfather prays twice a day in synagogue. And my grandmother said that God will help, that the shark cartilage will help, that the naturopathic professor will help, that it just takes time before the good cells start fighting the bad cells inside there.

Charley Davis lived in South San Francisco not far from 3Com Park. Back when 3Com Park was Candlestick Park, Charley Davis covered the Giants and the fights for the San Francisco Chronicle. His house was half a mile from the highway and set high on a street of identical houses. Charley let me in and asked me to follow him into the living room. He was wearing blue pajamas under a faded brown robe. He dragged his left leg and his left arm hung as rigid as a penguin’s flipper. His house was covered in old fight posters displaying pictures of guys I recognized and would have traded lives with, even though they were already dead. As Charley inched into his armchair and tried to organize his limbs, I concentrated on a framed shot of the Johnson-Jeffries fight.

When he was settled, I sat down on the couch across from him and told him that I was stuck with my Choynski research. I pronounced the name the way he had taught me over the phone: Cohen-ski. He asked me if I figured I could identify Choynski in one of the pictures at the Johnson-Jeffries fight. Choynski had worked Jeffries’ corner for that Great White Hope fight in Reno. After I passed that test, we went through our collective Choynski information.

“He was a candy puller.”

“Yeah.”

“Do you know what that is? ”

“Not really.”

“Me neither.”

“He was a blacksmith before he was a candypuller.”

“He fought out of the California Club when he met Corbett on the barge.”

“When he worked in the candy factory, he trained at the Golden Gate Club.”

“His father was a publisher. Some Jewish paper.”

“He had his own later, Public Opinion. Isadore N. Choynski. He had a bookstore. He graduated from Yale.”

“His mother didn’t like him boxing.”

“He wore his hair long and got into plenty of fights on the docks.”

“He lost those two fights to Goddard in Australia.”

“He taught Jack Johnson what he needed to know to become champion when they spent a month in a Galveston jail in 1901.”

The further we went on, the more we had to restrain ourselves from rushing into each other’s arms for the joy of it. I mean, I almost rushed; Charley wasn’t getting around that well anymore. Don’t look for him in the Boston Marathon, he said.

There really wasn’t that much material on Choynski and I turned out to know more than Charley. Back then, I was the world’s greatest authority on Joseph B. Choynski and I still didn’t know him at all. I told Charley I didn’t know where else to go. I’d run out of places to look for Choynski and didn’t like to think that I’d never find him.

I didn’t tell him about wanting to know another kind of everything about Choynski. I wanted to follow him as he walked home at night. I wanted to know what he smelled like, to hear the sound of his voice, to know the dimensions of his wife. I wanted to know if the reason he never had kids was because he had taken too many low blows.

“Fighters then were like hobos. Fights were illegal almost everyplace. They just drifted around. There weren’t any of those commissions back then and all those letters they have now: wbo, wbc, ibf, whatever the fuck they are. Look, some places boxers were celebrities, most places they were just trying to make a buck.”

Charley invited me back the next day so he could give me a picture of Choynski to copy. He would have had it ready that day, but I could have been full of shit and he didn’t like to waste his time on morons.

After that day with Charley, I did my tour of San Francisco. I looked up 1209 Golden Gate Avenue where the Choynski house used to be. It had been destroyed in the 1906 earthquake. A new development was there in its place—based on old photographs and a general idea, but built according to modern formula. The candy factory at Third and Stevenson was nowhere to be found and nobody knew where to look for the Golden Gate Athletic Club, although, in the late 1880s, it stood on the same corner.

I went to the San Francisco Public Library and looked again through the old San Francisco Call Bulletin microfilm. I read about a six-day bicycle race at the Mechanics’ Pavilion. The winner was a guy named Miller who rode an Eldridge-brand bicycle 18,000 times around the track for a total of 2,192 miles. This was February, 1899, about the time when Choynski fought Kid McCoy and lost the decision. After the fight, Eddie Graney, “sportsman, politician and Joe’s best friend,” suggested that Joe quit the fight game since he was no longer the man he used to be.

Each day, my grandmother lost something more of herself, as if the disease knew that one day had passed and the next had begun. One day she could sit in a chair in her bedroom, the next day she couldn’t get out of bed, and the day after that she couldn’t turn herself over. A nurse came every other day to look at her; another woman showed up every morning to clean the house and bathe her. Once, when everyone believed she could no longer get up, she walked halfway to the bathroom in the middle of the night, fell, and cut her cheekbone on the dresser.

Every word she said was reported to me, although close to the end she wasn’t saying very much. One day my mother heard her moan and asked where it hurt, and my grandmother replied her heart. My mother panicked because the doctors hadn’t said anything about her heart. My grandmother said her heart hurt for what will happen to my grandfather after. As always, my mother assured her that she would get better. “Idiot,” my grandmother said, “don’t laugh at your mother, soon enough you’ll be crying.”

Charley had dedicated one bedroom entirely to his boxing memorabilia. He had an award from the Boxing Writers Association of America and a picture of him receiving it in 1982. He had press passes from fights in Atlantic City, Tokyo, Sacramento, and other places. There were autographed pictures and framed shots of old-timers. In his closet, he had a filing system of cigar boxes, plastic lunch pails, and tackle boxes. There were gaps on the walls where he’d sold some of his pictures—protruding nails and whitish rectangles denoted absence. Five shots of Tunney and Dempsey had paid his medical bills.

As he fished around for the right cigar box, Charley suffered another stroke and dropped everything onto the floor. I wasn’t fast enough to catch him on his way down, but his right shoulder hit the hardwood first and cushioned the blow to his head. When he fell, Charley scattered some of his old press passes. One with a picture of him from the seventies landed on his right pajama leg. The picture testified to the fact that Charley had once been a handsome man.

Before her illness, I used to sit in my grandmother’s apartment and listen to her gossip on the phone to her friends in Yiddish. I used to sit with her, my grandfather, and the rest of them as they talked about the war. Before the war, they knew how to make ice skates out of wire, wood, and rope. My grandfather made them exactly the same way in Latvia as my great-uncle in Lithuania. Before the war, my grandmother recalled, there was a character called a sharmanka who went from town to town. He had an accordion and a little white mouse, and he could predict the future. (In Russian, he was called a katarinshik, my grandfather interrupted.) When the sharmanka came to her shtetl, all the children ran after him and gave him a few pennies. But my grandmother believed that even if she had asked the right questions, she couldn’t have changed the way things turned out.

Still, during the war they all saw miracles—which meant they remained alive while Germans died. God proved himself to them even though there was more of the same kind of evidence against him.

Since they offered, I rode along in the ambulance with Charley. I sat in the back with two attendants. Charley was in bad shape for most of the ride but, by the time they stabilized him, he had his own room, and I found myself lingering around the hospital waiting for I wasn’t sure what. The doctor had started relying on me for information about Charley, and since I liked the idea of being a participant in the final drama of Charley’s life, I gave the doctor the impression that I knew Charley better than I did.

When I checked in on him later that evening, Charley was awake but couldn’t speak. The doctor was asking him about his family. There were papers that the doctor needed signed, just in case. Charley could only communicate by writing things down on a pad with what was left of the motor functions in his right hand.

“Do you have anybody you want to contact? ”

Charley rolled his eyes to that. It was identical to a gesture that a perfectly healthy person would have made.

“Brothers? Sisters? Children? ”

Charley moved his eyes away from the doctor to the other side of the room.

“If you have children, Mr. Davis, you should tell them. They would want to know about this. There may not be another chance.”

Charley shook his head wearily. It didn’t mean there weren’t any children; it meant he wished the doctor would leave him alone. The doctor walked over to Charley’s right side with the pad and a pencil. He held it in front of Charley’s face and waited.

Charley wrote: jim fresno

“Is that his last name, Fresno, or is that where he is? ”

Charley shut his eyes and turned his back on the doctor.

There were eight James Davises listed in Fresno and only three of them were home. None of them had a father named Charley Davis in San Francisco. I left five messages for the other James Davises—four on machines and one with a Mexican cleaning lady.

After dinner, I got a call from one of my James Davises who said he had a father in San Francisco named Charley Davis.

“What did your father do for a living? ”

“He was a sportswriter for the Chronicle. He wrote about men trying to knock each others’ heads off.”

“I think you should come to San Francisco.”

Jim Davis wore khaki Dockers and a red golf shirt embroidered with the Promise Keepers logo. He had flakes of dry skin and an eyelash on the lenses of his glasses. He worked for a real-estate brokerage, and he appeared at the hospital just after midnight.

Charley was sleeping when his son arrived, and the doctor didn’t think it would be a good idea to wake him. By this point, I was very familiar with the locations of all the snack and coffee machines.

One of the first things Jim asked me was if I belonged to a church. I told him I did not. He asked if I had a personal relationship with Christ. His father, he said, never allowed Christ into his heart; he had never come to accept Christ’s love.

As we sat in the waiting area eating carrot muffins out of plastic packages and drinking coffee, Jim told me a story.

“I have a friend in my church group who was a troublemaker as a kid, and his dad worried about what would happen to him. His dad wasn’t a religious man; he worked for the phone company in Sacramento. But his dad made a deal with him. He told my friend that if he went to church with him every Sunday for a year he’d get him anything he wanted. You know, within limits, but really anything. My friend, he agreed, except for Little League when that was on Sundays. And he did it. Both him and his dad, every Sunday for a year except Little League. And when the year was up, his dad asked him what he wanted and you know what he said? He said ‘I want you to promise to keep going to church with me.’ That the two of them would keep going to church together. Him and his dad.”

As I listened to the story, I tried to anticipate the ending. I had heard something similar from one of my Hebrew School teachers.

After Jim finished his story, he wrote a list of verses that he was certain would help me to develop a personal relationship with Christ.

When Charley woke up, the doctor called Jim in, and I decided it was probably time for me to go. A nurse caught up to me as I waited for the elevator. Charley was calling for me; he was getting excited, and I had to come right away.

Inside his father’s room, Jim was kneeling by the bed. He was weeping and repeating:

“Daddy, I love you; Jesus loves you. Jesus loves you very much, Daddy! Do you know Jesus loves you? Jesus loves you very much, Daddy!”

The nurse held the pad so Charley could scrawl. Ignoring his son’s hysterics, Charley wrote: make sure about my things

I told him I would.

make sure jesus doesn’t get them, he wrote.

In the elevator, my phone rang. It was well past one in the morning and I felt sick as soon as I heard it. I let it ring once more even though I could have picked it up. When I picked it up, a man’s voice without a Russian accent said hello. A doctor, I thought, although it didn’t make sense.

“It’s Jim Davis.”

“Yeah Jim, what is it? ”

“What do you mean, what is it? What happened to my father? ”

“What do you mean? ”

“What do you mean what do I mean, you called didn’t you? ”

“I don’t understand. Where are you? ”

“In Fresno. Where the fuck do you think I am? Where the hell are you? ”

“I’m—”

“What the fuck is going on? ”

“Are you sure you have the right number? ”

“Are you fucking sick? Whoever the fuck you are, you talked to my maid this afternoon.”

Just after I hung up, the phone rang again. This time it was my cousin.

“Why was your phone busy? ”

“I don’t know.”

“Come home.”

In the background, I heard everyone crying. My mother was already reaching for the phone. She said in Russian:

“Kitten, babushka is gone. There is no more babushka.”

Charley’s place was only fifteen minutes away from the airport. I went there first and found the Choynski picture he’d promised me. It was one I didn’t already have. It had been taken in the early eighteen-nineties when Joe was at his peak. In the photo, he is wearing black tights and his shoulders and arms are taut with muscle. I didn’t feel bad taking it since I was sure Charley meant for me to have it anyway. For the rest of his things, I intended to call Canastota and the Hall of Fame.

There was a morning flight to Toronto and I slept for a few hours on Charley’s couch before going to the airport. It occurred to me how, with technology, it was possible never to miss a funeral.

On the plane, I read over Jim’s list of verses for a personal relationship with Christ.

John 1:12 We can become Gods children

Rom 3:23 We are all sinners and need Gods grace

Hebrew 9:27 We ultimately must pay the consequences of our misdeeds

Revelation 3:20 We must open our heart to Jesus and ask Him to come into our life

At the bottom, he’d left me his phone number and drawn the sign of the cross.

I never called him or looked up the verses. At home, we didn’t own a New Testament, but I found the prayer I had loved best in Hebrew school. It was taught to me by a beautiful Sephardic woman who was also my fourth-grade Hebrew teacher. We sang it every morning during prayers.

From out of distress, I called to God; with abounding relief, God answered me. The Lord is with me, I do not fear—what can man do to me? The Lord is with me among my helpers. I will see the downfall of my enemies. It is better to rely on the Lord than to trust in man. It is better to rely on the Lord than to trust in nobles. All the nations surrounded me, but in the Name of the Lord I will cut them down. They surrounded me, they encompassed me, but in the Name of the Lord I will cut them down. They surrounded me like bees, yet they shall be extinguished like fiery thorns; in the Name of the Lord I will cut them down. My foes repeatedly pushed me to fall, but the Lord helped me. God is my strength and song, and He has been a help to me. The sound of rejoicing and deliverance reverberates in the tents of the righteous: “The right hand of the Lord performs deeds of valor. The right hand of the Lord is exalted; the right hand of the Lord performs deeds of valor!” I shall not die, but I shall live and recount the deeds of God.

It was a fighter’s prayer.

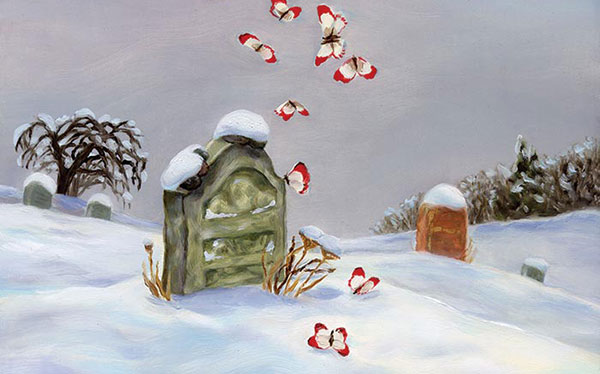

They buried my grandmother in a plain pine box. By the end, there was hardly anything left of her. In her final week she could hardly eat, and ultimately it had become too painful for her even to swallow water. I was told that she had died unconscious, shrieking for breath with an IV in her arm.

During the funeral, I only cried for my mother’s sake, and before that a little because I saw my grandfather lost and weeping like an old Jew. Even when her pine coffin reverberated like a bass drum with the first shovelfuls of dirt, I was okay.

It was only later that night, when I was on my hands and knees in the cemetery, that I wailed in Russian: Babushka, babushka, g’dye tih maja babushka? Babushka, babushka, where are you my babushka? I cried shamelessly, up to my elbows in the snow, searching for the new dentures, which they had neglected to bury with her. Bearing the dentures, I had driven out into the worst blizzard since 1944 with neither a flashlight nor a shovel. I had gone to the cemetery even though my mother had forbidden it, and even though Jewish law dictated that nobody was allowed at the grave for a month. But I felt that I was following other laws. And so I dug—first with purpose, then with panic. My hands burned and then went numb. Snow soaked through my shoes and pants. By the end, I didn’t even want to bury the teeth any more, I just wanted not to lose them.