This story was included in our November 2023 issue, devoted to some of the best writing The Walrus has published. You’ll find the rest of our selections here.

It is human nature to want a tragic accident to mean something. Drew Nelles, a former senior editor at The Walrus, offers a counterpoint in this memoir about his long-time close friend Dan Harvey, whose spinal injury in grade eleven left him paralyzed. In gorgeous, tender prose, Nelles questions the belief that Harvey’s suffering holds any “cosmic truth,” or that his friend is here to teach us “something about the value of human existence.” The push to redefine the assumptions around disability has, in the decade since this piece was published, continued to change our language too. In some cases, person-first language—“person with disabilities” instead of “disabled person”—may be preferred. “Body and Soul,” which initially emerged at the literary journalism program at the Banff Centre, went on to receive a National Magazine Award honourable mention. Today, Harvey lives in London, Ontario, with his wife and child, where he runs City Lights Bookshop. —Harley Rustad, senior editor, November 2023

Dan Harvey was a fat kid, which is probably why we became friends in the first place. In the rigid corporeal hierarchy of childhood, you’re either the right weight or you’re not: too big and you’re a fat-ass; too skinny and you’re a faggot. We were a perfect pair, like something out of a children’s tale: the Elephant and the Giraffe, as we nicknamed ourselves during a trip to the Toronto Zoo. What might it be like to take up a different kind of space in the world? But Dan and I were stuck with the bodies we had.

We grew up on neighbouring cul-de-sacs in Guelph, Ontario, and our elementary school was nearby. During recess, Dan sat by himself near the school doors, flicking pebbles at nothing. I was stick thin and bookish. Without a father, I had never learned to move like the other boys, didn’t know how to throw a football or swing a bat. So Dan and I found each other. In junior high, as cliques hardened, we drew closer, sitting for hours in his wood-panelled basement, where we talked about bands—Radiohead, Tool, Pink Floyd—in the rockist shorthand of teenage boys.

Dan played the saxophone then, and he looked as if he were fighting the thing, his cheeks red and puffed, his pudgy fingers manipulating the keys. He was, more than anyone I’ve ever known, an embodied person, moving like a tank and altering the gravity of any room he entered. He highlighted his curly brown hair with blond and often wore two shirts at a time, as if trying to constrain his bulging proportions.

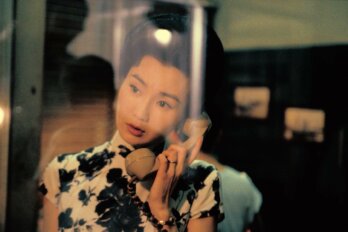

In grade nine, Dan and I attended the Halloween dance. Kids strutted around like pubescent bowerbirds, and we lurked on the fringes, terrified of the costumed girls around us. A few of them approached. One, a short brunette with blue eyes and a wide smile, had noticed Dan. She was dressed as a bee, black and yellow antennae wiggling on her head. I pushed Dan—who was convinced that he’d die a fat virgin—in her direction.

“I hear you like me,” Dan said.

“Yeah.”

“Do you want to go out?”

“Yeah.”

They danced the rest of the night, the girl’s hands reaching up to rest on Dan’s shoulders, his fingers closing around her waist. As we walked home, Dan realized that he had forgotten to ask her name. It was Jess.

By now, Dan’s rolls were starting to solidify. While I remained gawky, he developed into a natural athlete, his size—six feet four and nearly 300 pounds—an asset instead of a humiliation. He played football and basketball but grew to adore rugby, addicted to the sheer physicality of the sport. Acting also drew him in, and though he was usually typecast as the dumb jock or the idiot sheriff, he loved the attention. It was a way of attracting the spotlight on his own terms; you couldn’t call him fat if he called himself fat first. When we formed a band—I took up the guitar, Dan played bass—he sometimes prefaced performances with an apology. “If I mess up, it’s not my fault,” he told the audience. “I was born with fat fingers.”

He was still the closest friend I had, but I resented him too. He had buddies on the football team and a girlfriend; he lost his virginity two years before I did. When he got his driver’s licence, I started treating him like a chauffeur. I was not allowed to stay out past midnight, and I was terrified of driving, so after parties, Dan took me home in his parents’ Sebring before returning to the kegger to get drunk and sleep on the couch. Even as he ferried me around, I made sure he knew which of us was the smart one, who was the better musician, and who could name the studio where The Bends was recorded. Dan rarely said a word in reply. He just fidgeted uncomfortably, pushing his mass deeper into the seat, lifting one hand from the steering wheel to adjust his blue Tar Heels cap.

At the beginning of grade eleven, Dan got the red and yellow Superman logo tattooed on his right bicep. He had always been obsessed with the superhero, collecting comic books and Christopher Reeve movies and T-shirts. Superman, originally from the dying planet Krypton, is an attractive idol, his body a hard pile of muscle, capable of scattering bullets and soaring through solar systems. In Superman: The Movie, from 1978, he even turns back time by reversing Earth’s rotation. Superman is so unbeatable that his creators had to invent an antidote to his abilities: kryptonite, a mysterious green element that renders him powerless.

On Friday, May 23, 2003, just before the end of the school year, a few gym teachers and a dozen student athletes headed to a resort on Lake Rosseau, in Ontario’s cottage country, for the weekend. Dan and some friends rode with their teacher in his black Chevrolet Monte Carlo, and during the long trip north, the guy rolled down the sunroof and lobbed a full paper cup of Tim Hortons coffee at another car in their convoy. The cup arced in the air, brown liquid spooling out, before bursting across the windshield. The boys in the Monte Carlo laughed. Dan did too, but then he paused. Jesus, he thought. We could have killed them.

At the camp, the students played golf and tennis, and Dan showed off his easy confidence, hoisting other students on a rope swing and playing guitar around a bonfire. On Saturday night, though, the sky opened up and it rained. Forced indoors by the spring storm, the kids headed to the gymnastics building. As he jumped on a trampoline, Dan landed awkwardly and broke one of his big toenails, which began to bleed. He considered stopping, but instead he wrapped his toe in a Band-Aid and continued bouncing. He felt weightless up there in the air. Around 8 p.m., an instructor announced that their time was up. The kids begged for an extra ten minutes. She relented.

Dan turned his attention to the tumble tramp, a long, narrow track made of flexible fibreglass rods and foam mats, stretching toward an L-shaped concrete pit filled with yellow foam blocks. He took a breath and ran, springing off the stiff give of the tramp, preparing to cannonball into the foam. Then, at the very end, his newly bandaged toe caught the tramp’s protective edge, and he was thrown forward, curling into a crouch, and hurtled headfirst into the pit.

Dan plummeted downward, all 290 pounds of him, slicing through the yellow foam blocks at a near-perfect ninety-degree angle. He fell one, two, three metres below the surface, and he felt his forehead against the mesh that held the blocks a few precious centimetres from the pit’s concrete bottom. The net gave way beneath his momentum, and against that unforgiving floor, he hit the crown of his head—the part that when he was a newborn was still soft, before the plates of his skull closed. He felt a spark of pain in his neck. Then the net pushed back and his body came to rest on the blocks, and in the suffocating darkness of the pit, Dan realized that he could not move.

Unless you’re paralyzed, it is difficult to understand the sensation of actually being paralyzed. Your brain tells your body to do something, and your body doesn’t respond. Dan tried to lift an arm; nothing. He tried to kick a leg; nothing. He saw visions of faces—his parents, Jess, maybe even me—and each face was weeping. “Help me,” Dan tried to say, but his voice was weak, and he had difficulty breathing. “Help me.”

Sensing that something was wrong, two teachers and two students leaped into the pit and started flinging the blocks out. As they uncovered him, Dan flailed his head, the only part of him now responding to his mind’s commands. “Please, just turn me over,” he begged. He was convinced that everything would be fine if only he could look up. The teachers knew enough not to listen to him and called 911. Forty-five minutes later, an ambulance arrived. One of the paramedics jumped into the pit, lost his balance, and fell on top of Dan. In a rage, a teacher lifted the man up and threw him off.

The paramedics fitted Dan with a plastic cervical collar and secured him to a backboard. Only then did they turn him over. “He’s heavy,” someone said. “We’re going to need help.” Six people hoisted him from the pit, and the paramedics carried him outside toward the ambulance. It was pouring. As he looked up at the night sky, he could feel the rain on his face but nowhere else.

The paramedics hooked him up to IVs for fluids and sedatives, and as the ambulance tore across the Canadian Shield, Dan repeated three words, over and over: “I’m so scared.” It took about an hour to reach the hospital in nearby Parry Sound. He was taken to a triage room, where doctors measured his blood pressure and started to cut off his clothes. He was wearing one of his favourite T-shirts, adorned with Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon rainbow, and he asked the staff not to damage it. They told him they had no choice.

“Well,” Dan said, “at least don’t cut the logo. Cut around it.”

The hospital staffers looked at one another. One of them, a younger man, cracked a smile. “It is a pretty sweet shirt,” he said. They did as Dan asked.

Between the panic and the drugs, it was hard for him to make sense of what was happening. The doctors and nurses swirled around him, and he heard someone use the word “catheter.” He wasn’t sure what a catheter was; it just sounded bad. As the staff continued their work, he sensed, but could not feel, that they were sliding something into his genitals.

Later, a teacher came to see him and asked how he was doing. “They stuck something,” Dan said, his mind looping, “in my balls.”

The human spinal column has thirty-three vertebrae: the first twenty-four are separated by flexible discs, while the bottom nine are fused—five into the sacrum and four into the tailbone. When Dan’s head hit the floor of the pit, his spine collapsed on itself like an accordion slamming shut, an injury called a compression fracture. His C3 and C5 vertebrae, at the midpoint of his neck, jammed themselves together, shattering the C4 in between. As it burst, shards scattered and partially sliced Dan’s spinal cord, the bundle of nerves that connects the brain to everything else in the body. Those stray pieces, some of which still pressed against his spinal cord, had to be removed to prevent further damage. He was put in an ambulance again, this time heading to Sudbury Regional Hospital, two hours away and better equipped for such delicate surgery.

He was intubated and hooked up to a ventilator; his diaphragm had been partially paralyzed. The next day, over the course of several hours, the doctors operated. The surgeons sliced open the right front side of his neck, clamped back the skin and muscles, and removed the remnants of his C4. They then embedded a small chunk of bone, scooped from the iliac crest on the rim of his pelvis, and grafted it between the C3 and C5. Over time, the graft would fuse with the rest of his vertebral column.

The day after the surgery, he lay in his hospital bed. The ventilator breathed for him, his chest rising and falling. The intubator had been replaced by a tracheotomy, which bypassed his voice box, and he could no longer speak properly. A middle-aged doctor came in with a group of interns. “This is one of our quads,” the doctor said, as if Dan were not there or could not hear him. “He’ll never walk again.”

On Sunday morning, I was awoken by a phone call. It was Debbie, Dan’s mother. “Dan got in an accident,” she sobbed. “My baby is going to be in a wheelchair forever.” The light was pale grey through my window, and I was still half asleep. I had never known Debbie, who had a difficult relationship with Dan, to call her son her “baby.”

That day, as I did every Sunday, I went to work at the Cinnabon in the local mall. My mind raced. Would Dan truly be in a wheelchair forever? Would he be able to use his arms or hands? Could the injury be temporary? News of the accident spread, and over the course of the day, a stream of kids from school trickled into the Cinnabon to ask me for details I didn’t have. There were even rumours that Dan was dead.

Here’s how you make a dozen Cinnabons. Sprinkle a little flour on the counter. Take a mound of prepared dough and roll it out into a large rectangle. Smear it with room temperature margarine, then apply a layer of brown sugar and spices. Roll the rectangle into a long tube, slice it into individual buns, bake, and top it off with a dollop of sweet cream cheese icing. The task, which I loathed, felt different on this day. I noticed the dexterity of my fingers as they manipulated the dough, the shift of the muscles in my forearms, the effortless way my limbs seemed to know what to do. Under the fluorescent lights, in my ridiculous fast-food uniform, my movements seemed graceful for the first time, their possibility a miracle.

The spring of 2003 was the height of the SARS outbreak in Toronto, and hospitals closer to home wouldn’t take Dan. Unable to visit him in Sudbury, I wrote to a Radiohead fan site, asking if they could inform the band of his injury. They responded with a letter saying they were very sorry about the accident and that they would tell Radiohead when the band returned from touring. I also snapped a picture of our band’s practice room, in my mother’s basement. On the whiteboard on the wall, I had written, “Your babies are waiting to be played,” with arrows pointing to Dan’s Fender P-Bass and his fifty-watt Yorkville amplifier.

Although his C4 was destroyed, meaning he should only have been able to control his neck and (partially) his diaphragm, Dan’s spinal cord was not fully severed. This meant his brain might eventually manage to send some signals to certain areas for which the nerve connections happened to be intact. In other words, he might regain some limited movement. Even while I allowed that he might be permanently paralyzed, I imagined him as one of those sporty, active paraplegics who play basketball and rocket down the sidewalk. I even thought having a bassist in a wheelchair would give our band some cachet.

One afternoon, his father called me from the hospital and offered to hold the phone up to Dan’s ear. Because he couldn’t really respond to my words, it felt as though I were speaking into a void. Although I genuinely wanted to talk to him, to offer reassurance and a familiar voice, my words seemed somehow dishonest, my tone falsely upbeat. What could I tell him that was true? Only that I loved him, that I was sorry. But both of these things seemed too naked, too gloomy, so I said neither.

A week and a half after the accident, Dan was airlifted to Hamilton General Hospital. There, he underwent another operation, to remove more bone shards from his neck and stabilize the graft with titanium rods. Nurses switched his indwelling catheter for an intermittent one, which carries a lower risk of bladder infection but must be inserted and removed every few hours. (Before the accident, Dan had endlessly fantasized about women touching his dick, but this was not what he had in mind.) They also slowly weaned him off the ventilator, a half hour or an hour at a time, and it was a relief for him to be able to smell and speak properly during those brief windows. On my first visit, he was still intubated, and we struggled to communicate. His skin was green and translucent, and he refused to meet my gaze, as if angry that I had come.

I spent as much time as I could with Dan as the weeks wore on. One day, I was hanging out in his room when his leg moved. He had been having regular muscle spasms, which, several times a day, seized his legs in violent tremors. This looked different, more controlled—a shift rather than a sudden kick. I was elated.

“You can move your leg!” I said. When a nurse came in, I pointed. “That’s not a muscle spasm, right? He can move his leg.”

The nurse looked at Dan, then shifted her gaze to the floor. She was silent for a moment.

“I’m pretty sure,” she said softly, “that’s a muscle spasm.”

The blood drained from my face. The nurse left the room, and for the first time since Dan was injured, I felt tears in my eyes. He would never walk again, and there was no point in pretending otherwise. I stood at the foot of his bed, watching his leg, which was now twitching uncontrollably. My face began to move in spasms too, and I wept.

Once Dan transferred to a nearby rehabilitation hospital, Chedoke, life settled into a routine. After a fitful night of sleep, the nurses arrived every morning at 8 to insert a catheter and serve his breakfast of choice: Froot Loops and chocolate milk. Around 9, they gave him a rectal suppository, which they nicknamed the “magic bullet.” They turned him onto his side and, with gloved, lubricated fingers, stimulated his bowels until they emptied. He said it was like being probed by aliens.

If it was a Tuesday or a Thursday, the nurses used a Hoyer lift—a sinister-looking mechanical arm on wheels—to transfer him into a shower wheelchair. He evacuated into a toilet, where gravity could do most of the work, and the nurses washed him in the roll-in shower. Then they dressed him in a T-shirt and sweatpants.

At noon, an attendant wheeled him to the cafeteria for lunch. By now, he had some use of both arms. His right, especially, was growing stronger, thanks to physiotherapy and reduced spinal swelling, and he slowly learned to feed himself, using a white Velcro strap around his wrist, into which he inserted a fork or a spoon. Different types of food were more or less difficult to eat. Peas were a nightmare, but he loved Chedoke’s big Swedish meatballs, which were easy to spear. He had lost over 100 pounds since the injury.

Physio was at 2 p.m. Early on, the physiotherapists attached straps to his arms and legs and roped him to a metal grate anchored to the ceiling, for stretching exercises. They focused on his shoulders, which were in constant pain due to his lack of mobility. Later, he lifted small weights on pulleys and pedalled a device called an arm bike, but only with his right arm. His left was still too weak.

Hand class, which he despised, came at 3. The patients performed exercises such as drawing pictures, to help their dexterity. One particularly humiliating task involved stacking small plastic cones. Although Dan could use his arms, he could not move his fingers, which curled limply, so he had to pile the cones by holding them between his wrists. “I have no hands,” he said. “Why am I going to hand class?”

Not all physiotherapy felt like medieval torture. After a few weeks, he began to swim in the pool. A pair of physiotherapists attached a flotation device to his neck and transferred him onto a lift, which rotated and lowered him into the warm water, and he just floated there for a half hour or so. The reduced gravity made it easier for him to move his arms, and it was surreal to simply not touch anything. He was so accustomed to lying in a bed or sitting in a wheelchair. Visiting hours started at 4, dinner at 5:30. Bedtime arrived a few hours later, whether Dan was ready for it or not.

Dan’s first powered wheelchair was the bulky Invacare Storm. He felt that its prominent headrest made him look sickly, and it had rear-wheel drive, which made turning on the spot difficult. Next, he tried the Quickie S-646, a chair that advertised its RockShox—the same shocks he had once had on his mountain bike. Eventually, he settled on an Invacare Xterra, which was smaller, with mid-wheel drive. It was blue, like Superman’s uniform, and Dan had his younger brother attach small Superman stickers to the hubcaps. He also bought a manual backup wheelchair. It was neon green, and he could not move it himself, so he called it his kryptonite.

As his recovery progressed, Guelph newspapers frequently ran profiles of him, because his story lent itself to triumph-over-adversity narratives. Thanks to his love of the comic-book hero, the reporters gave him a rather condescending nickname: Superdan. One front-page photo showed him wearing a Superman shirt emblazoned with abdominal muscles as fake as his smile. In those stories, there was never any mention of a certain disquieting parallel: Christopher Reeve had become a quadriplegic in 1995 when he was thrown from a horse.

Playing his part with the reporters, Dan was upbeat, sometimes referring to his accident as a “speed bump.” In real life, his self-deprecating wit took on a new edge of bleakness. He wheeled around in mad circles and sang a song to the tune of the Toys “R” Us theme:

I don’t wanna grow up. I’m a handicapped kid.

Fell off a trampoline, and look what I did.

I fell into some foam, and they couldn’t find me.

I screamed for my life, and now I can’t go pee.

On Halloween, a group of us decided to go trick-or-treating around Chedoke. We were far too old, but Dan insisted: “Who’s gonna say no to a kid in a wheelchair?” He went as a cheerleader. He already wore white compression stockings to improve his blood circulation, and with a plaid kilt and a long blond wig, he looked like a slapdash drag show on wheels. We roved around a nearby suburb, silently daring the homeowners to refuse us.

Later that night, he went dark, as he often did. When the nurses put him to bed and the rest of us lingered on, he turned to our friend Jef.

“Jef,” he said, “I think you’re going to have to learn how to play bass.”

“I don’t really want to do that, man,” Jef said.

“Well,” Dan said, “you’re going to have to. I’ll never be able to play again. I just won’t.”

That year, my mother was diagnosed with cancer and required immediate surgery. Although her initial stay in the hospital was brief, my sister and I regularly accompanied her to follow-up appointments and a few additional surgeries. (She has since recovered.) My life began to feel like an infinite cycle of interchangeable hospital visits: the sweet chemical smell of hand sanitizer, the rooms full of downcast eyes and pale-pink furniture, the fluorescent lights, the long, dark hallways, the kindness or brusqueness of doctors and nurses.

There is a story my mother likes to tell. Many years ago, when my father was dying of melanoma, she took me to the hospital for a visit. I was two. Chemotherapy had ravaged my father, robbing him of his hair and his athletic build. But when she put me on his bed, I looked up at him and said, “My big, strong daddy.”

Now, sitting in a succession of waiting rooms, I did not feel so resolute. The bodies of those around me had turned against themselves: cells divided in a panic, limbs refused to flex. Through it all, my own flesh remained intact, unharmed. The athlete was paralyzed, and the bookworm walked on. Whatever force had decided Dan’s fate, I thought, it preferred great tragedies to small ones.

Discrimination against physically disabled people is so insidious because it is material, built into the infrastructure of bipedal existence. Liberal meritocracy finds ways to subsume women and queers and ethnic minorities, but it freezes in the face of disabled people, who make clear the extent to which we must evolve if we want to broaden the scope of our empathies. It is one thing to change a law or a bigot’s mind; it is quite another to install a ramp and an elevator in every building in the world.

Dan moved home at the end of November. His parents had bought a wheelchair-accessible van for $52,000 and converted their main-floor sunroom into his new bedroom. With the addition of a new bathroom and a roll-in shower, this cost $55,000. They installed an elevator in the back of the garage, as well as a ceiling-track lift in his room, and purchased an adjustable bed, all for about $20,000. Although fundraising helped offset the costs, his parents still went about $75,000 into debt. They considered selling the house and buying one that was already accessible, which probably would have cost less, but Dan asked them to keep it. He wanted things to remain as normal as possible.

But when he returned to high school, he struggled to reintegrate. Mercifully, at least, he turned out to be a talented student. The old Dan’s highest academic ambition was to become a gym teacher (neither of his parents had gone to university), and the only novel he had ever read from beginning to end was a Hardy Boys book, when he had chicken pox as a child. In his wheelchair, without the distractions of rugby or the band, he realized he was pretty smart.

Still, he had missed a whole semester and could not manage a full course load. He would not graduate with the rest of our class. He felt conspicuous in the hallway. Everyone knew him, and everyone was too nice. He continued to use the intermittent catheter, which meant that, every day, one of his parents came to school to help him pee. One day, before his scheduled urination appointment, his bladder grew too full and he pissed himself in drama class, a puddle spreading on the floor beneath his wheelchair.

Meanwhile, his relationship with Jess was suffering. Before, he had loved to drive; now that he couldn’t, he literally became a back-seat driver. When Jess drove his van, he grew agitated, telling her she was taking corners too fast or parking poorly. She faced the impossible task of making an unhappy person happy, and her patience wore thin.

Dan often did not want to go out at all. Getting strapped into the van and finding somewhere wheelchair accessible to go was just too much hassle. I spent a lot of time with him at his house, watching cable television and superhero movies, although not in the basement, where we had wasted so much of our youth. The only way to get down there was by using the stairs.

I wasn’t always there for him. Just as Dan had predicted, Jef learned to play the bass, and with Dan’s reluctant blessing, I formed a new band with a few others. A grade twelve event that year featured musical acts performing at the school. We set up our equipment at the end of a hallway, near the display cases and swinging doors. High on the neck of my Fender Telecaster—black with a white pick guard, just like Jonny Greenwood’s, from Radiohead—I played the opening notes: D-A-A-D-A-A, then two ringing strikes of a harmonic G.

A crowd gathered, and Dan came to listen, his unusable hands folded in his lap. He stared glumly at the floor. Although he had known this moment would arrive, he was overcome. He should have been up there with us, roaming the stage like a dinosaur as he once had. His wide, ruddy face grew red as tears poured down his cheeks, and he fled into a corner. When the other students stopped to help, he begged them to leave him alone.

Prom snuck up on the rest of us, but Dan had made meticulous preparations. He ordered a suit from Moores, specially tailored for his needs: longer in the back to comfortably tuck beneath him and shorter in the front to avoid bunching. He made sure to book a limousine bus that was wheelchair accessible. When the day came, we went to Jess’s house in the country for photographs. There is one photo in particular that I love: five of us—Dan and me and three of our closest friends—our arms around each other’s shoulders, corsages on our lapels, faces grinning and eyes squinting in the light.

But once we arrived at the convention centre, Dan sat on the sidelines, watching the rest of us dance, pressing against each other, young and self-conscious but in full possession of our bodies. He recalled an event he had attended a few months earlier, where he saw men in wheelchairs dance with their lovers in their laps, and he remembered the first time he met Jess, back when her arms still wrapped around his neck and her blue eyes looked up at his. He turned to her. “Do you want to dance?” he asked.

She refused, embarrassed at the thought. That night, during the prom’s Most Likely To awards, Dan and Jess won Most Likely to Get Married.

Later that summer, Jess came over to Dan’s house and sat on his adjustable bed. “We need to talk,” she said. She didn’t want to be his nurse; she needed to have her own life. He said goodbye to her in the driveway, and as she drove away, he let himself cry. No one would ever want him again. Who would fuck a guy in a wheelchair?

I left for university in Montreal that August. For the first time ever, Dan and I lived not just in different neighbourhoods, or even different cities, but different provinces, hundreds of kilometres apart. Dan, though, resolved not to stay in Guelph either. The following year, he was accepted into the media, information, and techno-culture program at the University of Western Ontario, in London, where he fell in love with theory. He devoured Donna Haraway’s seminal feminist essay, “A Cyborg Manifesto,” which posits that because there is no longer any distinction between humans and the machines we create, we are all organic-inorganic hybrids. He was also intrigued by the Freudian theory of scopophilia—the voyeuristic pleasure derived from looking at others. Thinkers like bell hooks had applied the theory to racial othering, and Dan recognized it in the gaze of those around him, who either gawked at his wheelchair or scrupulously avoided looking his way.

At least one person, though, did not seem to find Dan repulsive: a young, good-looking personal support worker. As Dan neared the end of undergrad, they had a fling, which, to put it mildly, is against the rules. Their relationship was brief, but it proved to Dan that he was still attractive. He began to research vibrators—some men with spinal injuries are able to achieve orgasm with sufficiently intense pulsation—and settled on a Hitachi Magic Wand. The day after it arrived, he sent me a Gmail chat message:

Dan: I’ve got a good story for you, but I’ll save it for later.

Drew: no, tell me now!

Dan: well, I’ve been doing some research for a while and talking to various urologists about my “baby making juice.” And after almost 7 years of hibernation, I finally made it work last night . . . I had a party. I was/am the happiest person on the planet. It’s gross, but I had to tell you.

Drew: ahahahahahahahahahahahaa

thank you so much for sharing

wicked

i’m happy for you

Dan: Ha ha. Thanks, dude . . .

I wonder if Hallmark has a card for this occasion.

Dan still longed to drive again. He found an American company, Electronic Mobility Controls, that manufactures equipment for disabled drivers, and he bought a white Ford E-250, which he had modified to fit his chair. (A lawsuit against the athletic camp and the school board, settled out of court, had brought him enough money for such purchases.) A company called Sparrow Hawk Industries, in Waterloo, Ontario, put it all together. He took driving lessons, and in 2008, he became the first disabled Canadian owner of a van with EMC’s joystick controls, using a computer system called Advanced Electronic Vehicle Interface Technology, or AEVIT 2.0.

That December, I went home to Guelph for Christmas, and he invited me for a ride. I climbed into the van. He sat in his wheelchair on the driver’s side. He pressed a button, and a robotic woman’s voice spoke.

“You now have voice activation. Please press the Alert icon on the display if you wish to disable AEVIT. The AEVIT is performing a backup self-test. Do not move the input devices during this test.”

He paused while the system ran.

“I am now verifying your control of the gas-brake functions,” the voice said. “Please manually operate the AEVIT input device in both the gas and brake directions.”

He pushed the joystick forward, then back.

“I am now verifying your control of the steering functions. Please manually operate the AEVIT input device so the vehicle’s steering wheel rotates all the way to the right and to the left.”

He pushed the joystick to the right, and I watched in awe as the steering wheel followed, as if by magic. He pulled out of the driveway, and we roamed around the suburbs, the snow falling around us. Occasionally, the computer misheard his voice commands, randomly turning on the blinker or the windshield wipers. I laughed at the science fiction futurism of it, and I felt very young. We were sixteen again, and Dan was chauffeuring me home.

I have learned things from Dan: how to sit quietly beside a person who needs my presence, how to operate a lift and strap a wheelchair into a van. But I am resistant to the idea, occasionally suggested, that disabled people are here to teach us something about the value of human existence, that the rest of us should treasure what we have, for it might be taken from us tomorrow. The lives of disabled people have intrinsic importance, independent of whatever they might offer the able bodied. When accidents like Dan’s occur, our first instinct is to scour them for meaning, but there is no cosmic truth here. There is only the random lightning strike, the explosion of a dying planet—only suffering and our capacity to overcome it.

Today Dan looks completely unlike the boy he once was. His cheekbones and shoulders and elbows and knees are as sharp as knives. A permanent catheter enters his bladder through an incision in his abdomen, and he takes a litany of medications: baclofen for muscle spasms, gabapentin for neuro-pathic pain, Senokot to soften his stool, Fosamax to strengthen his bones. He fidgets in his wheelchair, leaning forward and then back, lifting his arms as high as he can. The Superman logo on his bicep has deflated, but his right forearm now bears a quote from Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five: “So it goes.” He also has a puzzle piece tattooed on the back of his neck, just above that ruined vertebra—a reminder that a part of him is missing.

He still lives in London, in an accessible house also bought using money from the lawsuit, with two cats and his fiancée, Jennifer, an occupational therapist. (They’ve asked me to be best man at their wedding this summer.) He drives himself almost everywhere. Last year, he finished his master’s at Western; his thesis examined television coverage of the genocide in Rwanda. Before he begins his PhD, he is taking a break to write a novel about a boy paralyzed in a car accident.

I don’t see Dan as often as I used to. We talk on the phone and visit when we can. Last summer, I stayed with him for a few days in London, where we barbecued veggie burgers on his back deck and went to the movies. We were supposed to see Radiohead in Toronto, but the day of the concert, the stage collapsed. Three crew members were hurt. A drum technician died.