AComplicated Kindness by Miriam Toews is one of the all-time great Canadian novels. It spent over a year on bestseller lists in Canada and won a host of prizes, including a Governor General’s Award. It’s almost two decades old now, but it still reads as tender and jarring as ever. It’s told from the perspective of a scrappy-but-wounded teenager dealing with the same angst everyone goes through at that age—plus the added challenge of missing her mother and older sister, who have absconded from their tiny Mennonite community.

This is how the novel renders dialogue:

Yes, yeah, that’s me, I said. Gloria scanned my face. No scars though, she said. I wanted to scream: THAT’S WHERE YOU ARE SO UNBELIEVABLY WRONG!

The absence of quotation marks helps the text lean, uninterrupted, into the jagged stream of consciousness of a disaffected teenager trying to maintain an ironic distance even from her most difficult emotions. It’s a successful union of form and content, where everything is given the same undifferentiated weight because everything feels equally heavy.

The choice can be somewhat disorienting, and it can take readers a little longer to get into the book’s flow. But it’s a choice that’s increasingly common in modern fiction. Some of the best and buzziest contemporary writers—Sally Rooney, Ian Williams, Bryan Washington, Celeste Ng, Ling Ma—render their dialogue free of quotation marks. The reasons vary, but more writers are dropping speech marks to explore distances between readers and narrators and even to eliminate hierarchies.

Going quote free can in large part be attributed to modernist writers who eschewed quote marks as part of a larger experimentation with form. Dorothy Richardson, whose thirteen-volume novel series, Pilgrimage, affirms and encourages feminine self-actualization, wrote that she dropped quotation marks for feminist reasons: women should have the freedom to write “without formal obstructions.” Other writers of the period were less political in their rebellion against punctuation—or just wanted to experiment.

Today, many writers who go quote free, Toews among them, say it’s more of an instinct than a specific choice. Quotation marks are “just not my thing,” Toews told me in an email. “It just felt right at the time, when I started writing one hundred years ago, and I never stopped.” To start using them now would feel alien, she said. “I often don’t even know where they actually go, they look a bit messy on the page.” (In an interview with Oprah Winfrey, Cormac McCarthy cited James Joyce in a similar explanation for making the same choice: “There’s no reason to block the page up with weird little marks,” McCarthy said. “If you write properly, you shouldn’t have to punctuate.”) But Toews acknowledges that the choice has allowed her writing to embody a certain propulsive rhythm: “I didn’t want quotation marks to slow me down.”

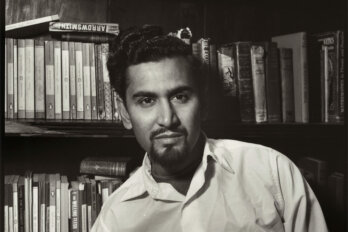

Choosing not to demarcate what a character observes and what they say out loud is still a rare enough choice in fiction that it can communicate urgency or poignance; it can create the sense that there’s no separation between a character’s experience of the world and the world itself. Billy-Ray Belcourt avoided quotation marks in his novel A Minor Chorus, one of the most acclaimed Canadian books of last year, in part, he said, because of his unnamed narrator’s subjectivity. The book wouldn’t exist outside of the character; everything filtered through his experience. “Maybe because it’s in the first person, I couldn’t rely on the omniscience of complete memory,” Belcourt says. “It didn’t make sense to me to suggest that what these characters were saying was something that the protagonist would be able to seamlessly recall.”

Many contemporary novels that style dialogue no differently than internal narration play with that sense of how subjective everything is: rather than position their narrators as impartial observers, these novelists draw attention to just how implicated they actually are. Ian Williams used quotation marks in his 2011 short story collection, Not Anyone’s Anything, but left them out of his 2019 novel, Reproduction. “Their absence indicates to me the fluidity between our language and our thoughts or between our language and our being,” he told Hazlitt. “We tend to think of language as something that’s intended for the outside but really language is constantly running inside of us. It’s hard to know exactly where a sentence starts.”

Sally Rooney made a similar point in a 2018 interview about Conversations with Friends. “I don’t see any need for them, and I don’t understand the function they perform in a novel, marking off some particular pieces of the text as quotations,” she told Stet. “I mean, it’s a novel written in the first person, isn’t it all a quotation?”

Belcourt’s choice not to use quotation marks in A Minor Chorus feels especially deliberate given the self-consciousness on display in the book. The narrator, a young Cree man in Alberta, decides early in its pages that he wants to write a novel. The book is about family and alienation and about Canada’s colonial legacy, but it’s also a novel about novels—what they can accomplish as well as their limits.

At the book’s opening, and again toward the end, the narrative is handed over to Jack, the narrator’s cousin, who has had a difficult life and is now serving time in a detention centre as he awaits a criminal trial. For pages at a time, someone besides the narrator tells the story, with Jack’s sections rendered in italics. “The italics felt to me like I was tapping into the lyric voice—a voice that is immediate and bodily and perhaps requires a certain kind of intensity and rhythm,” says Belcourt, who’s also an established poet.

But that wasn’t the only reason he made that choice. “As I was working on this novel, I felt very aware of the history of the English novel as [something] that’s meant to fetishize individualism, and I didn’t want to write a novel that did that,” he says. “My decision to ultimately write a novel that takes a kind of oral history approach was my way of subverting their history.” The Jack sections, as well as the gradual use of “we” in place of “I,” were part of an attempt “to gesture to that collective voice.”

Belcourt welcomes the departure from convention and any tiny rebellion against strict literary rules that sparks “a lot of different kinds of small subversions by writers.”

The movement away from quotation marks may be contagious. Deborah Levy used them in her acclaimed 2019 novel, The Man Who Saw Everything. But she was tempted not to, she told Penguin UK, because “most of the contemporary writers I admired had skillfully ditched them and I knew this was the way to go.” Lauren Groff has abandoned them in most of her recent work: “Quotes feel declaratory, as though the speaker steps onto a pedestal before they speak,” she wrote on Twitter, now known as X, in 2021. And Don Gillmor also got rid of them for his new novel, Breaking and Entering. “Removing the quotation marks changed the mood in a sense and created a slight distance that altered the feel of the prose,” he said in an interview with his publisher, Biblioasis. His inspiration: two Canadian writers he admires, Lisa Moore and Miriam Toews.