I was present in Warsaw, Berlin, Budapest, and Prague in 1989 when non-violent revolutions swept the Communists from power, creating a brand new model of regime change. I stood in Wenceslas Square as hundreds of thousands of people rattled their keys, unleashing an eerie, shimmering sound into the air, chanting, “Your time is up!” I had lived among the Czechs for a decade in the 1970s, and I felt the power of their relief as the hated regime slipped into history.

So, not surprisingly, I was intrigued by the instant media punditry comparing the bloodless revolutions in central Europe with the recent wave of Arab uprisings in the Middle East. Even on television, I could see similarities between Prague 1989 and Cairo 2011: the peacefulness of protesters; the prominent role played by young people; the sparkling displays of public eloquence and wit; the sudden release from fear and the rebirth of civic pride; the infectious jubilation when the regime was finally brought down. But I saw big differences as well.

In 1989, British historian Timothy Garton Ash, having a celebratory beer with Václav Havel, observed that in Poland it had taken ten years to overthrow the system, in Hungary ten months, and in East Germany ten weeks; Czechoslovakia would perhaps take ten days. He was simplifying, of course, yet his remark captured something of the truth of the moment: Soviet-style Communism was a unified system run, with some minor local variations, from Moscow, and its collapse overturned the old Cold War domino theory—the belief that if Communism were not contained militarily it would spread to other countries. The revolutions of 1989 marked the end of an era, and provided an occasion for joy and optimism to everyone who had lived so long in the shadow of nuclear Armageddon.

Even from my armchair in front of the television, I could see that the events in Tahrir Square were charged with a different energy and a different meaning. Without knowing much about the misery Hosni Mubarak had inflicted on his country, I could still feel the enormous, pent-up frustration of protesters who, day after day, pushed back against the police, braving tear gas, truncheons, armoured cars, rubber bullets, and buckshot, not to mention the stones, Molotov cocktails, and bullets unleashed against them by the regime’s thugs and sharpshooters. Hundreds died and many more were injured. The battle of Tahrir Square looked and felt like a real revolution.

Yet the outcome remained far from clear. Mubarak was gone, but he was instantly replaced by an interim military junta that promised to step down after elections later in the year. The military had allowed the revolution to take its course—one of the slogans in Tahrir Square was “The people and the army are one hand!”—but as a governing body it was ham-fisted and slow, and the popular trust it enjoyed at first soon began to fray. The 1989 revolutions had been swift and decisive, their outcomes never really in doubt; Egypt’s revolution appeared to be bogging down, and had succeeded only in comparison with those in Libya, Syria, Yemen, and Bahrain, where the violence continued unabated.

Meanwhile, less optimistic analogies had begun to surface. Drawing parallels to abortive revolutions that swept through Europe in 1848 implied that the Arab revolts were vulnerable to suppression, at least in the short run. Comparisons with the 1979 revolution in Iran suggested that they could lead to nasty Islamic theocracies across the region. The Communist countries of central Europe all had unified opposition movements that were almost like governments-in-waiting and enjoyed Western support, whereas the Arab Awakening had no such coherence and seemed to make many neighbouring countries wary, even fearful. I could understand why an absolute monarchy like Saudi Arabia might feel threatened, or why Israel might worry about the future of its relationship with a democratic Egypt. But why were so many pundits outside the Middle East worried? And why in Prague, of all places, were those who had been on the front lines in 1989 asking whether the Arabs were ready for democracy? Didn’t we believe, in general, that even an imperfect democracy was better than none? Or had that belief now become so battered that we no longer trusted it?

I wanted to learn more, which is how I found myself in Cairo in March, six weeks to the day after the fall of Mubarak.

To a newcomer, the Egyptian capital can feel overwhelming—overwhelmingly brown, overwhelmingly dusty, overwhelmingly noisy, and overwhelmingly crowded. During the day, the major roads and elevated highways are jammed with bleating, blaring bumper-to-bumper traffic that appears to obey no known rules. And yet, except in rush hour, vehicles move efficiently. Walking is an adventure, and merely crossing the road (there are no crosswalks and few traffic lights) can seem like an extreme sport. The secret, I discovered, is to be bold: make your intentions clear, step out into the flow of traffic, and wait for the cars to stop, slow down, or flow harmlessly around you as you make your way to the other side alive. This experience holds a lesson: In Egypt, not everything that appears chaotic or dangerous is necessarily chaotic or dangerous. Even in matters as basic as driving habits, there is an unwritten social contract everyone understands.

Two-thirds of Greater Cairo’s population, which is approaching 20 million, live in what are euphemistically called “informal areas,” tracts of densely crowded concrete and brick buildings, some many storeys high, tightly clustered along narrow streets and laneways without regard for plans or building codes or zoning bylaws, often without access to utilities or policing. The people who live and work in these areas are mostly poor, getting by on the equivalent of a few dollars a day. And yet these are not, strictly speaking, slums or ghettos, and the streets feel relatively safe.

In downtown Cairo, which is almost European in spirit and design, the main streets teem with life, especially after dark. Clusters of boisterous young men hang out on the sidewalks, while young women walk by, arm in arm, ignoring them, or pretending to. Most women cover themselves in public, usually with a hijab or head scarf—one of many signs that Islam has made inroads into what was once a more secular society. The amplified calls to prayer that punctuate the city’s din five times a day reinforce this impression. But, as their driving habits demonstrate, Egyptians have an ambiguous relationship with rules, both religious and secular. Many young women wear colourful, outrageously flamboyant hijabs, almost pharaonic in their puffed-up splendour, which seem intended to attract rather than discourage male attention. And while they also observe the diktat against visible flesh, they frequently wear tight-fitting jeans and long-sleeved sweaters that leave little to the imagination. (Sexual harassment is a serious problem in Egypt; I was told that as more women cover themselves, the incidence of assaults has actually increased.)

I heard a joke in Cairo that encapsulated the Egyptian habit of flouting the law: “We pretend to obey the rules, and they pretend to enforce them.” It reminded me of one they told in central Europe before the fall of Communism: “We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us.” Put side by side, the two jokes help to explain the differences between the two societies on the cusp of revolution: the anarchic vibrancy of Egypt versus the homogeneous monotony of central Europe.

When the former Polish dissident Adam Michnik contemplated the devastation that remained after decades of Communism, he came up with a memorable metaphor: Communism turned an aquarium of living fish into fish soup, he said. Our challenge is to turn the fish soup back into an aquarium of living fish.

When the Communists took power in Eastern Europe after World War II, they adopted the Soviet model and set about destroying the traditional institutions of civil society. When they were done, virtually nothing was left standing: no private property, no market economy, no independent businesses; the media entirely under state control; the churches, Catholic and Protestant, eviscerated. A single political party called the shots, and a massive security apparatus backed it all up. This was Michnik’s fish soup, and the problem confronting the new leaders after the revolution was how to bring their societies back to life. Yet they faced the future with some important assets: a high literacy rate, no real poverty, and ex-leaders who had not robbed the country blind, mainly because the centrally controlled economy produced little worth stealing (“We pretend to work, and you pretend to pay us”).

Egypt was still a colourful aquarium, despite the efforts of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the country’s first modern military dictator, to make Soviet-style fish soup of it. Anwar al-Sadat, his successor, attempted to remedy Nasser’s excesses by opening up the economy. So, in turn, did Hosni Mubarak, and today the results can be seen everywhere. Upscale Cairo neighbourhoods boast opulent neon malls selling Western clothing, cars, and services; international corporations like FedEx and Vodafone have put down roots; and Tahrir Square’s most prominent commercial landmark is a KFC outlet.

Cairo’s traditional economy seemed vigorous as well. In the narrow streets beyond the downtown core, I saw block after block of tiny workshops and wholesale outlets producing and selling plastic piping, car repair tools, packing materials, belt buckles, shoe parts, picture frames, bolts of cloth, bales of raw cotton, and on and on—all of it supporting a cottage industry economy that apparently operates beyond regulation (“We pretend to obey the rules, and they pretend to enforce them”). Judging from the number of newspapers and magazines, a lively press exists in Cairo, livelier now that censorship has been relaxed and pro-Mubarak editors have been let go. The judiciary, I was told, remains relatively independent, and the universities—once strictly monitored by the government—show signs of rousing themselves to a new, autonomous life: the American University in Cairo has just launched a new periodical called the Cairo Review of Global Affairs, devoting its inaugural issue to “The Arab Revolution.” Scholars at Al-Azhar University, whose pronouncements carry an almost papal authority in the Sunni Muslim world, have been calling on Egypt to establish “a democratic state based on a constitution that satisfies all Egyptians.”

It would seem, then, that not even the worst depredations of the Mubarak regime could suppress Egypt’s economic and civic vitality. Now, after the revolution, the country’s most serious problems lie elsewhere, in the realms of education, politics, and religion, a tangled and explosive mixture that holds the potential to derail a process so well begun.

I met Fady Phillip at a small but intense demonstration on the Nile embankment near Tahrir Square. A bearded cleric was speaking into two bullhorns, and several men were waving wooden crosses in the air. Off to one side, barely paying attention, stood a line of armed soldiers in camouflage fatigues. I approached a young man with a Palestinian kaffiyeh draped over his shoulders and asked him what was going on. He explained that some young Muslim men had torched a Coptic church in the Helwan district of Greater Cairo, for reasons having to do with a love affair between a Christian man and a Muslim woman. The Copts, a branch of Christianity whose presence in Egypt predates Islam, wanted to rebuild, but the authorities were dragging their feet about issuing the permits. This was, he said, deliberate discrimination.

When I took out my notebook, a small crowd gathered around me, and one man started peppering me with questions:

“Where you from? Who you write for? ”

Before I could properly explain, the questions turned rhetorical: “Where you think this revolution start? You think it start in Tunisia, yes? ”

“So I’ve been told,” I replied lamely. Simplified accounts of the Arab Awakening usually start with the self-immolation of a humiliated Tunisian fruit vendor, Mohammed Bouazizi, but I was prepared to hear another view.

“Ah, no, my friend, you are wrong,” said my interlocutor, delighted to have exposed my ignorance. “It start right here, in Egypt,” he said, pronouncing it Ezhypt, “in Alexandria.” He went on to tell me how, on New Year’s Eve, extremists had bombed a Coptic church in Alex, as everyone calls it, killing twenty-four people. Huge demonstrations followed. “Hundreds of thousands in the streets, my friend. That is where the revolution start. Do you know it? No, you do not.”

“That is because you no Egyptian,” someone else put in. “Egyptians eat beans. You no eat beans. Americans eat hamburger.” Everyone burst out laughing, and I felt like the straight man in an absurdist improv routine.

I turned to Phillip—by that time, I had his name—and said, “Look, I’d love to hear more about this, but can we go somewhere for a drink? ” I figured that as a Christian he wouldn’t be offended by the suggestion.

And so began a hair-raising dash through the traffic swirling around Tahrir Square, Phillip always a few paces ahead of me. It was Friday, and another large demonstration had taken place that afternoon; now it was evening, the crowd had thinned, and the atmosphere was more relaxed. A line of skinny kids who looked about twelve years old filed by to the rhythmic beating of an oil drum. Their faces were painted red, white, and black—the colours of the Egyptian flag. “Welcome!” they shouted at me as they passed. I looked around and noticed that we were standing in the very spot where pro-Mubarak horsemen and camel drivers armed with rifles and machetes had charged the protesters back in February, triggering bloody street battles that had raged for two days. The area was now populated by street vendors selling ice water, lemonade, Egyptian flags, “I ♥ Egypt” T-shirts, lapel pins, earrings, tricolour headbands, and other souvenirs commemorating January 25, the first day of mass demonstrations. This instantaneous, exuberant commodification of an event where so many had died left me with mixed feelings.

Phillip led me through a maze of narrow streets and back alleys, until we emerged into a brightly lit pedestrian mall filled with yellow plastic tables and chairs. A waiter appeared at our side, and Phillip ordered a soft drink and a sheesha, a water pipe in which café-goers smoke tobacco cured in fruit juice. I asked for a beer. Phillip shot me a pathetic little smile that read, “You must be joking.” I pointed to a big sign over the café door advertising Stella, a local beer. “That’s just for show,” he said. I ordered coffee.

We talked for the next two hours, interrupted by a steady stream of street vendors and the waiter bringing fresh, glowing coals for the water pipe. Phillip, who is in his mid-twenties, has travelled around the United States. “People say I speak English with a southern accent,” he said, although I couldn’t detect it. He also spent five years studying Islam, he told me, so he knows what he’s talking about. His main concern, he said, is Article Two of the Egyptian constitution, which enshrines Islam as the state religion and the principles of sharia law as the basis for legislation. The article has been in place since 1971, and though it has not led to extreme punishments, such as amputations and death by stoning, it remains lodged in the constitution like a poisonous pill, waiting to be activated should Islamic fundamentalists ever seize power. “If you want to see sharia in action,” said Phillip, “look at Saudi Arabia.”

As a Christian, he was unhappy with how events were unfolding. He’d been in Tahrir Square from the beginning, but on February 1, after Mubarak promised to step down, many of the “January 25 people,” as he calls the original demonstrators, felt they had made their point and went home. The following day, Mubarak unleashed his thugs, and the Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt’s oldest Islamic organization, stepped forward to take an active role in the square’s defence. Not wishing to concede ground to the Islamists, the January 25 people returned and joined in the fight. And when they had successfully secured the square, they and the Islamists demanded Mubarak’s removal. A kind of solidarity between Muslims and Copts had been forged, reflected in the T-shirts I’d seen on sale displaying the Muslim crescent and the Christian cross side by side.

“After Mubarak was knocked down, people said we’re either going into a dark tunnel, or we’re going into the sun,” Phillip said. “And according to what I’ve seen, it’s going into a dark tunnel.” It wasn’t just the continuing attacks on Christian churches; the results of the March 19 referendum worried him, too. The junta, or Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, as it likes to be called, asked Egyptians to endorse temporary changes to the constitution (Article Two was left intact), and to approve its proposal to hold elections in September in advance of a proper constitutional convention. Most of the January 25 people urged Egyptians to vote no. They argued that September elections wouldn’t give them enough time to establish new political parties, handing an automatic advantage to the better-organized political forces like the Muslim Brotherhood, which was campaigning vigorously for the yes side. Except in Greater Cairo and Alexandria, the yes vote prevailed, a result some clerics proclaimed as a victory for Islam.

To say that Phillip doesn’t trust the Islamists not to turn Egypt into a fundamentalist theocracy is an understatement. “Believe me,” he said, “I wanted Mubarak out, but I don’t want democracy.” When I asked him why, he said that in a country where 30 percent of the population is illiterate and gets most of its information from the mosque or from television, democracy could put the Islamists in power. The solution, he said, is to hand the country over to “a good, wise dictator who wants the country, not for himself, but for everyone.”

“And if this wise man starts abusing power? ” I asked.

“Then we will have another revolution,” he said.

“But isn’t that what democracy is? ” I asked. “A revolution by ballot box, so you don’t have to go to the streets every time you want a change of government? ”

He flashed me his pathetic smile. “You’re not talking about America,” he said. “You have to understand: Egypt is different.”

That night, I took a cab across the Nile, back to my hotel. The Kasr El-Nil Bridge, where the crowds had first pushed their way into Tahrir Square in January, teemed with people sitting on the sidewalks in plastic chairs, smoking, playing backgammon, eating and drinking and relaxing, away from the heat and dust of the day. This is almost a nightly ritual in Cairo.

In Cairo, as in Prague, the revolution unlocked in people a sense of self-worth and confidence that had long been suppressed. Typically, they describe the experience as a sudden release of energy. Nagham Osman, a young woman with a burst of curly auburn hair, was studying film when the revolution broke out. “For years, they put fear in all of us,” she told me when we met at a coffee shop near my hotel. “This is a renewal and a rebirth. I don’t want to sleep. I wake up at five o’clock in the morning. I’ve just turned thirty, and it’s a very nice birthday.” She said her sudden loss of fear had caused changes in her behaviour. She had recently surprised herself by standing up to authority figures in a way she had never dared before.

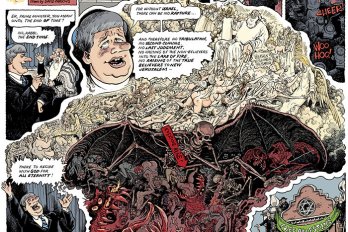

Osman told me that with Mubarak gone, Egyptians had begun talking freely about politics, about the constitution, about issues that had never occurred to them before. Even those who had supported Mubarak, she said, were enjoying the new sense of freedom. All over Cairo, lectures and cultural events related to the revolution were being held. “This has been a very big change in me and in my friends,” she said. “People own the streets now.” As if to prove her point, students from a nearby art college had been painting a series of murals a block away from the coffee shop, works-in-progress that symbolically expressed their response to the revolution, in styles ranging from old-style agitprop images to comic book realism and graffiti.

I had observed this sudden, emboldening release from fear in Prague right after the velvet revolution. It’s surprising, because the fear had seemed so permanent and so crippling. We tend to believe long-term exposure to fear will leave behind permanent psychic scars, akin to trauma. But when such regimes leave the stage, this primal fear seems to vanish with them, like a wisp of smoke in the wind. Why? Perhaps because the fear represented a natural, rational response to a real situation. It was not delusional, like paranoia, or neurotic, like anxiety, and when the cause was removed the effect went with it. Yes, such regimes do inflict lasting harm on their subjects, but what causes more damage are the relentless humiliations and privations of everyday life—the petty corruption, the destruction of privacy, the need for constant pretence that Václav Havel called “living a lie.” For truly effective techniques of social control, you have to look not to the police, but to ideology and religion.

Osman’s understanding of revolution borders on the romantic. “I like the saying ‘When the student is ready, the teacher will appear,’” she said. “I think the revolution happened when people were ready for it. It was almost as if something came and changed everyone, and then the revolution could happen. It was a perfect time.”

Aly El Shalakany is an Egyptian Canadian lawyer in his late twenties who, thanks to the revolution, is about to embark on a path he could scarcely have foreseen a year ago: democratic party politics.

He spent part of his childhood in Canada, earning an undergraduate degree at the University of Toronto; studied law at the University of London, and worked at a prestigious City firm for three years. He returned to Cairo in 2009 to practise corporate and commercial law with the family firm. His tidy, well-appointed third-floor office overlooks a shady street in an upscale yet oddly down-at-the-heels district called Zamalek. He’s a self-assured man with short, dark, curly hair and a closely trimmed goatee, who favours crisply ironed shirts, open at the neck, and casual slacks. “‘Duty’ is a heavy word,” he told me when I asked why he’d come back to Egypt. “I like to get involved, I’m socially active and multi-faceted by nature, and I felt I could make more of a difference here than in London.”

I asked him what the country was like before the Arab Awakening, and, like a good lawyer outlining a brief, he laid out the recent history of the pre-revolution, starting with the creation in 2004 of the Kefaya! (Enough!) movement, which he described as a coalition of NGO and opposition players, drawn mainly from the middle classes, that worked toward creating broader social and political awareness. In 2010, Kefaya! joined forces with a group called April 6th, a workers’ movement focused on cultivating solidarity across social classes. Because they were generally young, the April 6th people had mastered social media, and some had even studied the techniques of non-violent protest used by movements such as Otpor! in Serbia. Kefaya! and April 6th would sometimes stage small demonstrations, but they were easily outnumbered by the police, who routinely surrounded them and forced them to surrender using the infamous “kettling” technique (which made its ignominious Canadian debut at the G20 summit in Toronto last year.)

As El Shalakany tells it, three game-changing events took place in quick succession in 2010. That summer, a young Egyptian American named Khaled Said was beaten to death by the police in Alexandria. A young Google executive, Wael Ghonim, set up a Facebook page called “We Are All Khaled Said,” which became a call to arms. Next came Egypt’s November parliamentary elections, in which the ruling National Democratic Party won 420 of the 508 seats. “Everyone knew it was beyond rigging,” El Shalakany said. “They were just cramming it down our throats.” Then came the New Year’s Eve bombing of the church in Alexandria. El Shalakany said he believes it was a set-up by the Mubarak regime, which was “playing the Coptic card.”

“What does that mean? ” I asked.

The Copts, he explained, represent almost 10 percent of the Egyptian population, as well as the biggest potential ally in what could be a liberal movement of mainly secular forces. “So the regime has always tried to make the Copts feel, ‘Look, if it’s not us, it’s going to be the Muslim Brotherhood, and they’re going to eat you and cannibalize you and kill your children.’ Bombing the church was a way of them telling the Copts, ‘Look, there are real dangers out there, and we are the only ones protecting you. Without us, you’re screwed.’ The problem is that they handled it so badly that the Copts knew what was going on.” According to El Shalakany, the Alexandria bombing brought things in Egypt very close to the boiling point.

The revolution in Tunisia was taking place at the same time, and Egyptians were watching. On January 14, the night President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali was toppled in Tunis, El Shalakany invited a few friends over for drinks: “We were tuned to Al Jazeera, and we couldn’t really understand it,” he said, “because Tunisia had a guy exactly like ours, and they were repressed for thirty years. And he was also controlling them through fear, and through using their equivalent of the Muslim Brotherhood as the bogeyman. So they’ve managed to do this. Why can’t we? That was the spark, you know? ”

His story took me back to a church basement in Wroclaw, Poland. It was November 4, 1989, and the room was full of young Czechs who had illegally crossed the border into Poland for a weekend of Czechoslovak-Polish solidarity. I was sitting with a group of young women, watching a West German telecast of a massive anti-Communist demonstration in Leipzig. The women were mortified. “The stupid East Germans have beat us to it!” cried one of them. “It’s so shameful.” Five days later, the Berlin Wall opened up. Eight days after that, a student demonstration in Prague triggered the velvet revolution in Czechoslovakia; many of the kids from the Wroclaw gathering took part. Pride and humiliation make for powerful motivators.

By now, the Egyptian Twittersphere was abuzz, and El Shalakany and his cohorts were in the thick of things on January 25, when the crowds crossing the Kasr El-Nil Bridge grew so huge that for the first time they outnumbered the police, making kettling impossible. The protesters pushed through to Tahrir Square, and the Egyptian revolution was on. El Shalakany stayed with them until it was over. He has since joined the Egyptian Social Democratic Party, one of three new liberal (that is, secularist) groups that plan to field candidates in the election, now scheduled for November. Registering a new political party entails the fulfillment of several cumbersome, expensive, and time-consuming requirements: a minimum of 5,000 supporters—across at least ten governorates, or provinces—all of whom must sign notarized powers of attorney as proof of their commitment. The bureaucratic mindset can survive any regime change.

Like many secular Egyptians, El Shalakany believes the Muslim Brotherhood—a presence in Egypt since 1928—no longer poses a threat, partly because of its own divisive growing pains as it establishes its new political wing, the Freedom and Justice Party. Nor is he worried about the inclusion of sharia in the constitution. “The principles of sharia are the principles of Buddhism or Christianity or Judaism,” he said. “It’s very, very conceptual.” The important point, he stressed, is that the constitutional court has always interpreted sharia in this general sense. Making Article Two an election issue would create a major distraction, as would raising the issue of corruption in the army. Instead, El Shalakany and his party are focused on the long term. “We’re not naive,” he said. “We don’t think democracy is some kind of magic lantern you can just rub and everything will be okay.” Egypt is embarking on a ten-year process, he said, because it will take that long to develop a democratic political culture. His party’s platform includes generous helpings of social reform, programs to improve the country’s abysmal public education system, and plans for helping the poor. In the back of his mind, he harbours larger schemes: reclaiming more of the desert for agricultural use, and relocating the seat of government to a new, as yet unbuilt capital city. When I raised my eyebrows at this, he said, “Hey! We’re Egyptian. We’re not afraid of big projects.”

Jane Jacobs would have loved Cairo. It supports her belief that sidewalk safety in cities depends on what she called “the brains behind the eyes on the street.” The streets of Cairo, no matter what the neighbourhood, are always full of people, and not just passers-by but hangers-out: shopkeepers; shoeshine men; self-appointed parking attendants and car washers; and the ubiquitous bowabs, or doormen, on their rickety plastic chairs, keeping a half-closed eye on the comings and goings. Jacobs believed that street safety is gained through trust, and based on casual observations I would say trust at that very basic human level—something the Communists so thoroughly destroyed with their mania for creating surveillance states—remains alive and well in Cairo.

One day, I accidentally left my wallet, including a considerable sum of money, credit cards, driver’s licence, and so on, in a taxi. I had no receipt from the cab, and my wallet contained nothing to indicate where I was staying. The man I was interviewing that morning, Yasser Shoukry, took me to a dingy police substation near Tahrir Square, where he helped me file a report. Three days later, the taxi driver, whose name is Hamdy, showed up at my hotel with the wallet. Not a thing was missing. I offered him a reward, but he refused. Shoukry managed to slip some money into his pocket, but when Hamdy discovered it he called back, acutely embarrassed, and offered to drive me to the airport for nothing. How had he managed to track me down? After finding a business card in my wallet that belonged to Ali Abou Elela, a social activist who works for an Egyptian NGO called the Al-Shehab Institution, he drove to Elela’s office and learned where I was staying.

The Al-Shehab Institution is a community centre located in an informal district called Ezbet Haggana, not far from Cairo International Airport. Elela and I had been introduced electronically by Michel de Salaberry, a former Canadian ambassador to Egypt, who had helped the NGO in its early days with a modest grant from a program called the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives. De Salaberry clearly believes in the importance of small acts of charity, and he took a personal interest in the project; during his tenure in Cairo, he invited children from Haggana to play in the garden of his official residence every Friday. He still returns to Haggana for a few weeks each year to teach, and although the Canadian grant has long since run out he says Shehab has managed, “through the shoals of government control and the versatility of foreign funding,” to keep going and even to expand.

I met Elela and his colleague, Nawal El-Ramly, at their office overlooking Tahrir Square, and from there we took a taxi to their headquarters in Haggana. The area has a population of about 150,000 but no municipal water or sewage connections, which means that women have to carry heavy loads of household water from a communal tap. The district has just one government school, one medical clinic, and little or no policing. As we walked through the streets, it felt to me more like a bustling country village than a “slum,” as Elela calls it. It even has its own transport system, a fleet of pickup trucks and motorized tricycles called tuk-tuks that ferry people through the streets, stopping to collect them and dropping them off on demand.

Shehab is not the only NGO serving the area: Christian NGOs cater to the needs of the Coptic population, and Islamic NGOs work with Muslims. But Shehab is rigorously secular and welcomes everyone. It doesn’t dispense money; rather, its mission is to teach people to help themselves by laying claim to their civic rights: clean water, sewage systems, garbage collection, education, and health services. It also provides legal advice and vocational training, particularly to women. When I was introduced that day to a group of women who were learning the business of dressmaking, my presence caused quite a stir. They were all covered, but they flirted openly with me, and some of their comments were—as translated—quite ribald. Clearly, the setting made them feel free to behave in ways they would never have dared to in the street.

When I asked how they felt about the revolution, they offered mixed responses. Some called Mubarak a thief and said they were glad to see him gone. Others said they missed the financial stability of his regime. The sudden economic slowdown following his departure, coupled with a drastic drop in tourism, caused immediate hardship in a cash economy where people subsist without salaries, savings, or pensions, and depend on a daily trickle of money to survive. The women all agreed that the streets of Cairo were less safe now than before the revolution, and as I listened to them I realized that under the guise of governance Mubarak had been running a gigantic protection racket. When his “clients” called his bluff, he did what any gangster would have done: he turned loose his goons. What he hadn’t counted on was his clients’ willingness to fight back.

I asked Elela about the impact of the revolution on his work. He said it has “increased the value of participation,” going on to explain that before the revolution it had been hard to persuade people that collective action (like Shehab’s dressmaking co-op, for instance) could improve their lives. After the revolution, they understood—because they had experienced it directly—that there was power to be had in doing things for themselves. When Mubarak pulled the police off the streets, people banded together across the city to protect their properties, not just in affluent areas like Zamalek, but in places like Haganna as well. This was what Elela was talking about: Egyptians were learning that co-operation actually created a kind of social capital. After almost half a century during which the idea of active citizenship had been discouraged, this modest uptick in the desire to participate offered some encouragement.

When I returned to Cairo this past June, the level of anxiety seemed higher, although people were getting on with their self-appointed tasks. Aly El Shalakany’s party, the Egyptian Social Democratic Party, was soon to be officially registered and was already engaged in tentative discussions with the other liberal parties about mergers. A friend of El Shalakany’s, Rebecca Chiao, had created a website called HarassMap.org to address the problem of sexual harassment, by showing the areas of Cairo where women were at greatest risk. Khalid El-Biltagi, a professor of Czech literature whom I had sought out on my first trip, was translating an anthology of Václav Havel’s seminal essays on democracy into Arabic, assisting in the creation of a green party, and launching his own digital publishing business. Nagham Osman had been accepted into a course in human rights law at the American University in Cairo. A new newspaper, called Al Tahrir, was in development; and Hisham Kassem, the founding publisher of Cairo’s best daily, Al Masry Al Youm (Egypt Today), was hard at work building a state-of-the-art, twenty-first-century newsgathering operation.

A new electoral law, which would bring in a form of proportional representation, was in the works. The threshold for entry into parliament—2 percent—was set deliberately low, to encourage smaller parties to compete, although it will all but guarantee a parliament of small, squabbling parties that will be less effective as a governing body. A major attack on a church in Imbaba, one of the “informal” Cairo neighbourhoods with a high proportion of ultra-radical Islamists, had Fady Phillip and the Coptic community more worried than ever about the future. Many Egyptians believed the revolution was being sabotaged by the Saudis, who were suspected of financing the unrest. Meanwhile, Hosni Mubarak had been arrested and was in hospital, awaiting a trial scheduled for later in the summer. But most of the people I spoke with blamed the junta for moving far too slowly and for illicitly using the March 19 referendum as an endorsement to introduce dozens of unauthorized changes to the constitution. Even more disturbing was the junta’s tendency to resort to Mubarak-era repressive tactics. Since Mubarak’s departure, several thousand civilians have been tried in military courts on charges ranging from “thuggery” and assault to endangering Egyptian state security. Many of the accused are pro-democracy activists, or bloggers who had broken a decades-long ban on writing critically about the army. One blogger was sentenced to three years in jail for “insulting the military institution, dissemination of false news, and disturbing public security,” after having written a post demanding an end to conscription.

On July 3, after I returned to Canada, I received an email from El Shalakany that reflected the growing unease:

“Things have not been going so well over the past two weeks… There was a very saddening incident about a week ago where families of martyrs were beaten (allegedly more than a thousand injured) at a protest in Tahrir by the Central Security Forces, a branch of interior ministry. The details of why this happened have been supercharged with conspiracy theories, but the fact remains that huge elements of the police force still don’t get that things have fundamentally changed. There is a huge call to arms, to take to the streets on Friday 8 July to show them that we are not happy with the pace and inconsistency of change.”

As promised, on July 8 the biggest demonstration since last February took place in Tahrir Square. It was called Final Warning Friday, and in El Shalakany’s opinion it was “an absolute success in terms of putting pressure on [the junta].” A tent city was set up in the roundabout, and it remained there until August 1, when the army and the security police tore it down and forced the last remaining demonstrators to leave.

Three days earlier, on July 29, hundreds of thousands of radical Islamists—Salafis—gathered in Tahrir Square, giving credence to pessimistic predictions that the revolution would open the door to an Iranian-style Islamic republic. El Shalakany downplays that danger. According to his sources, he says, most of the Salafi demonstrators were paid to attend, allegedly with Saudi money. “If, after being paid, you max out at one million people, then that is merely 2 percent of the voting population,” he wrote. “If that’s all [they’ve] got, then actually we will be okay.” The greater danger to the liberal cause, he feels, would come from a potential revolt of the poor, forcing educated Egyptians to choose between military rule and a radical, class-based revolutionary government, neither of which would lead to the secular democracy he longs for.

On August 3, a military court airlifted ex-president Mubarak to Cairo, where he appeared in court on a stretcher to face charges of corruption and conspiracy to kill protesters during the uprising in January and February. As El Shalakany remarked, it’s the first time such a thing has happened in 8,000 years of Egyptian history. Yet the Mubarak trial, as important as it is—since it signals a commitment to the rule of law and bolsters the junta’s waning credibility—is not the main event. That will be the success or failure of Egyptians in creating a new democratic political order from the tatters of Mubarak’s hegemony.

But I’m still haunted by a question: why should we care?

Here’s my tentative answer. Egypt is the biggest country in the Arab world. Its cultural influence in the Middle East is akin to that of the United States in the English-speaking world. In religious terms, Cairo is to Islam what Rome is to Christianity. Should Egyptians show that it is possible to create a democratic, secular state in which Christians, Muslims, and Jews can worship as they please without politicians pitting them against one another in the interest of “stability,” then might not the contagion of democracy begin to spread throughout the region? And if that were to happen, might not the world become an easier place in which to live, even temporarily, as it did when the Berlin Wall came down?

I think about this every time I go through a security check at the airport. I think about it every time I hear someone argue that the war against terror will never end, or that the whittling away of our civil liberties, the legalization of torture, the creation of lawless extraterritorial prisons, the gradual criminalization of free speech, the massive intrusions into our privacy are all justified, because radical Islam poses a greater danger to us than the loss of our democracy. Maybe if the Egyptians create a democracy of their own, it will help us to rescue ours.

This appeared in the October 2011 issue.