Every tree, every plant, has a spirit. People may say that a plant has no mind. I tell them that a plant is alive and conscious. A plant may not talk, but there is a spirit in it that is conscious, that sees everything, which is the soul of the plant, its essence, what makes it alive.

—Pablo Amaringo, Peruvian ayahuasquero

In 1984, a young Ph.D. student at Stanford University named Jeremy Narby travelled to the Peruvian Amazon to conduct field research for his thesis in anthropology. Raised in Canada and Switzerland, Narby lived for two years with Peru’s Ashaninca tribes, and had read accounts of the remarkable healing abilities of their shamans. When he told the shamans about his chronic back problem, they offered him a plant-based cure, a sanango tea consumed when the moon was new. It would, they cautioned, leave him debilitated for two days, at first chilled and then unable to walk; afterward, he would be fine. Their forecast proved accurate; Narby drank the tea and felt chilled to the bone. When the cold abated, he found he could not stand. By the third day, the pain in his back was gone. Twenty years later, it has not returned.

Curious to learn more, Narby questioned the shamans about the source of their knowledge. They told him something that he—trained in the materialist, rationalist ethos of Western science—could scarcely comprehend: that their wisdom derived from spirits within the plants themselves. In other words, they said, the plants of the Amazonian rainforest spoke to them, giving precise instructions in the art of healing and a great deal more. Narby initially thought this claim was a kind of shamanic joke. He quickly learned otherwise.

For millennia, the indigenous peoples of South America have used plant-based potions to enter altered states of consciousness that confer medicinal and spiritual powers. The Ashaninca and dozens of other tribes derive their information via a foul-tasting tea known as ayahuasca (eye-yah-wah-skah), a Quechua word meaning “vine of the souls.” Others in the region know it as yage or caapi.

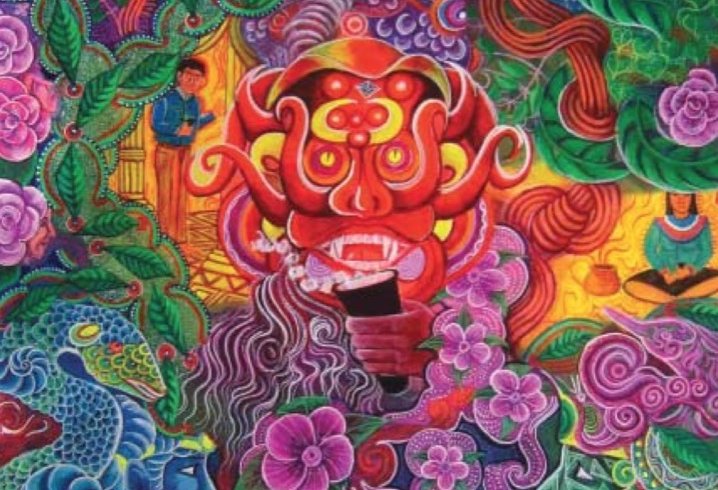

According to the shamans, the visions often induced by the drug—of coiled fluorescent serpents, prowling jaguars, and brilliant multicoloured tableaux of gardens, palaces, and lush forests—are not projections of the human imagination; rather, they are an alternate reality to which the brain’s receivers become attuned. Ayahuasca, they explained to Narby, is like “television of the forest.” When they turn it on, it is as though they are dialing up channels and communicating with spirits, possibly from other dimensions. The plant spirits, known as doctorcitos (little doctors) or abuelos (grandfathers), teach shamans how to diagnose illness, what plants to use for treatment, and what diet to follow. They also teach icaros, shamanic hymns that are sung to help summon the presence of the spirits. Indeed, music is an indispensable part of tea-drinking ceremonies.

Narby was fascinated. As he notes in his book The Cosmic Serpent, dna and the Origins of Knowledge, there are some 80,000 varieties of plants in the Amazon. To make ayahuasca, it is necessary to combine precisely two of them, a vine and a leaf that, morphologically, have nothing in common. The leaf (Psychotria viridis) contains N,N-dimethyltryptamine (dmt), a hallucinogen. Ingested by itself, the drug has no effect; a stomach enzyme, monoamine oxidase (mao), renders it impotent. The vine (Banisteriopsis caapi), however, contains three alkaloids that effectively turn off the mao, allowing the psychoactive ingredient of dmt unfettered access to the brain. In chemical composition then, ayahuasca is related to, but more complex than, psilocybin (derived from mushrooms) and, to a lesser extent, lsd (lysergic acid diethylamide, a synthetic).

How did ancient Amazonian tribes discover what is effectively a designer drug Surely not, Narby suggests, by trial and error; there are roughly 6.4 billion possible combinations of flora. Moreover, brewing ayahuasca tea is a laborious process during which the plant stems must first be pounded for days, then immersed in hot water with the leaves, then boiled for up to fifteen hours, and finally filtered. Even if the Ashaninca or another tribe simply intuited the potency of this specific leaf-vine arrangement, how would they have happened upon the complex recipe that must be used to make the tea There is no satisfactory answer.

Similarly, forty types of curare, the paralytic agent derived from seventy different plant species, are available in the Amazon. Making it requires collecting a precise combination of several plants, boiling them for several hours, and injecting the resultant paste under the skin. Could that have been discovered by trial and error

The shamans of the Amazon basin insist that plant gods, appearing during periods of extended trance induced by ayahuasca, taught them the secret medicinal properties of the plants that cured Narby’s aching back. These gods also taught them about curare and hundreds of other healers hidden in the botanical world. Their knowledge and its efficacy appear to be beyond dispute; it has, in myriad ways, been adapted and profitably exploited by the global pharmaceutical industry.

But for the empirical West, Narby observes, two fundamental problems arise. First, we regard hallucinations as illusions-projections of the mind that have no basis in reality. But if that precept is correct, and these visions are simply culturally specific phantasms of the brain, then how is it that Peruvian Indians, American businesspeople, Israeli scientists, Swiss anthropologists, and Canadian journalists tend to see exactly the same kinds of visions after drinking the tea

Second, the notion that under any circumstances plants might speak is anathema to Western science. Indeed, anyone who declares that plants communicate, let alone that they are capable of offering detailed tutorials in pharmacology, is likely to be treated for a psychological disorder. But if plants do not speak, then where does the verifiable knowledge of Amerindian shamans come from The universe of ayahuasca therefore poses a profound intellectual dilemma. Jeremy Narby wasnt at all sure that he could resolve the paradox, but he was determined to try.

In May 1999, US customs agents searched property belonging to Jeffrey Bronfman in Sante Fe, New Mexico. Bronfman is the leader of the American branch of O Centro Espirita Beneficiente União do Vegetal (the United Beneficent Spiritual Union of the Plants). The udv, as it is known, is a Brazil-based syncretic church—part Roman Catholic, part animist—that uses hoasca (the Portuguese transliteration of ayahuasca) as a sacrament in lieu of the traditional wafer and wine. Founded in 1961 and now boasting a worldwide membership of some 7,000, the udv is one of three well-established ayahuasca churches in Brazil; the others are Santo Daime and Barquinha.

Bronfman had imported the tea used in the twice-monthly ceremonies of his 130-member New Mexico congregation. The agents seized some thirty gallons of hoasca, possession of which is illegal under Schedule I of the US Controlled Substances Act, but laid no charges. The following year, Bronfman sued the Drug Enforcement Administration, alleging a First Amendment violation of the constitutional guarantee of freedom of religion. Hoasca, his lawyers maintained, was an essential sacrament—used exactly as peyote is now used, legally, in rituals of the Native American Church.

There was more than a little irony in all of this. Bronfman, forty, is a second cousin of Edgar Bronfman Jr., Warner Music Group chairman and scion of the famous Montreal family and its once-great liquor empire. In the 1920s and early ’30s, Edgar’s grandfather, Sam, built a vast fortune eluding federal agents and running alcohol from Canada into the US, where its sale and consumption were banned under the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Now, seventy-five years later, another Bronfman was using part of his inherited wealth to take on the US government in a landmark case involving another banned drug.

At the first hearing in 2001, a US district judge sided with Bronfman’s group and instructed the federal government not to confiscate the tea. The Department of Justice appealed the ruling, but the US Tenth Circuit Court in Denver upheld the injunction, twice. The Bush administration, however, was not prepared to surrender. Federal attorneys again appealed, this time to the US Supreme Court. It, too, sided with the udv on the narrow injunction issue, but later agreed to review the case. Thus, on November 1, 2005, did lawyers for both sides appear before America’s highest court to contest Gonzales, Attorney General et al v. O Centro Espirita Beneficiente Unio do Vegetal et al. The question at issue: whether the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, “requires the government to permit the importation, distribution, possession, and use of a Schedule I hallucinogenic controlled substance.” The battle had been joined: America’s commitment to religious freedom versus the decades-long war on drugs.

Ayahuasca is not a trip, certainly not the hedonistic kind often associated with lsd, to which it is sometimes compared. On the contrary, drinking the tea—Narby likens the taste to acrid grapefruit juice—is a challenging, often terrifying, and at times transcendent, life-altering experience. Physically, the brew commonly induces nausea, vomiting, farting, and diarrhea—humbling moments in a room full of other voyageurs. It purges psychologically as well; the visions and emotions it conjures up can rattle one to the core, laying siege to the artfully arranged fortifications erected on behalf of the ego. It is for good reason that members of the oldest of Brazil’s ayahuasca churches, Santo Daime, call ayahuasca ceremonies trabalhos (works). Spiritually, ayahuasca is often said to put users in touch with divinity, to connect them with the ineffable presence of God, or with the spirits of the dead, including family members. Ultimately, the drug—a word disciples of udv, Santo Daime, and the estimated seventy-two other ayahuasca-based Amazonian cultures firmly reject—seems to reveal the hidden, deeper, and essential meaning of things.

Making post-facto notes of his first overwhelming ayahuasca session in 1985, Narby wrote:

Images started pouring into my head…an agouti [forest rodent] with bared teeth and a bloody mouth; very brilliant, shiny, and multi-coloured snakes…. I suddenly found myself surrounded by two gigantic boa constrictors that seemed fifty feet long. I was terrified…. [T]he snakes start talking to me without words. They explain that I am just a human being. I feel my mind crack, and in the fissures, I see the bottomless arrogance of my presuppositions…. I find myself in a more powerful reality that I do not understand at all…I feel like crying in view of the enormity of these revelations. Then it dawns on me that this self-pity is part of my arrogance.

My own single experience with ayahuasca was not dissimilar. Forty-five minutes after I drank about five ounces of the tea, a wave of panic swept over me, as if my life itself were slipping away. I was powerless to stop it. I was cold and sweaty at the same time. In fact, I thought I was dying. The leader of the group I was with approached and suggested that I lie down. When I did, my legs and knees started shaking, rhythmically but uncontrollably. Later my whole body—lying supine on the floor—rocked visibly from head to toe, like a metronome, but again I was not the agent of the rocking. I had no ability to stop it. Like Narby, I was told—by thought—that I was nothing, a mere drop in the ocean. Images flashed before me at absurd speed, wild and intricate geometric patterns. Snake heads rose in front of my closed eyes and seemed to examine me. Oddly, they seemed benign and I had no fear of them. I felt—indeed, I knew—that I had been conveyed into the hands of some extraordinary power, the kind of power that traditional Judeo-Christian prayer frequently ascribes to God. I had uttered prayers thousands of times before, but had never genuinely understood them. Now, I found myself thinking okay, I get it. But I had no sooner conceived the thought than another replaced it: You haven’t begun to get it.

Are you God, I asked, phrasing the question as a thought.

God, Jesus, Mary, call me whatever you want.

How can you do these things, move my body like a puppet

The thought-answer came back instantly: I can do anything.

I had been instructed to concentrate on breathing—deeply and slowly; when I did, the shaking would instantly stop and, bathed in a light I had never seen before, I felt a sense of benevolence and well-being. I wanted to get up and hug the people around me, most of them strangers. Suddenly, the chasm between the human sense of self-importance and our true impotence struck me as wonderfully amusing, and I started to laugh. Later, still on the floor, I used my hands like a choir conductor to direct the singing of hymns that was going on constantly around me. My interpretation of the entire six-hour session—the lesson I felt I was being taught—was that it was time for me to wake up, get my act together, and show more love for those closest to me. Despite the initial terror, I concluded that I had been treated mercifully and regarded the experience as positive.

These accounts are typical. All of it—exotic, wondrous imagery, fear, utter annihilation of the ego, the forced encounter with personal issues one would rather not confront, some compelling apprehension of the sacred and the mystical, and the conviction that everything encountered is more real than the floor one stands upon—are commonly reported. But no two drinking experiences are ever exactly the same.

In the growing body of literature about ayahuasca, by far the most comprehensive and illuminating text is Antipodes of the Mind: Charting the Phenomenology of the Ayahuasca Experience, by Benny Shanon, a professor of cognitive psychology at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. “An entire continent resides inside our mind and Shanon has provided the map,” Narby explains. “His book gives the sense that Western man is still living in the sixteenth century, and the Americas have just been discovered. Westerners have thought that objective knowledge was the only way to know the world seriously. That’s all very well until what you want to deal with is subjective human consciousness. It’s impossible to be objective about the subjective. Consciousness is a first-person experience. It’s like swimming—you’ve got to be wet.”

During the almost six years it took him to write the book, Shanon, an otherwise traditional, Western-trained cognitive scientist now in his sixties, drank the sacred tea more than 100 times and interviewed 178 other users. Many of those interviewed by Shanon told him that taking ayahuasca was the most important event of their lives. His own experiences affected him profoundly. Gradually, he became aware that “what I was actually entering was a school…. The teacher was the brew.” His sessions of intoxication—his word—forced upon him a rigorous self-analysis. “One finds oneself having no other option but to address issues that are often neither easy nor pleasant.” When he started going to Peru and Brazil, Shanon confesses, he was “a “devout atheist.’ When I left South America, I was no longer one.” Ultimately, he writes, scientific investigation cannot unravel the mysteries of ayahuasca: “I am inclined to say that [it] brings us to the boundaries not only of science but also of the entire Western world-view and its philosophies.”

It was a measure of the importance attached to Gonzales v. udv that, marginal though ayahuasca culture is in the United States, the Supreme Court hearing drew the attention of every major and many minor religious and human-rights groups. Among those filing amicus curiae briefs in udv’s defence were the American Civil Liberties Union and organizations representing Baptists, Presbyterians, Evangelicals, Roman Catholic bishops, Jews, Muslims, Sikh Americans, and various independent scholars.

The insuperable hurdle confronting Deputy Solicitor General Edwin Kneedler was the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. It effectively gives objectors a presumptive exemption from laws that violate their religious beliefs. In the language of the act itself, no federal law shall “substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion” unless a “compelling governmental interest” is proven; even then, the law must be implemented in a way that is “least restrictive” to religious practice.

Kneedler mounted a tripartite argument: first, that the active ingredient in ayahuasca, dmt, posed a genuine danger to human health, leading to anxiety, dissociative states, and psychosis; second, that if udv were allowed to import the brew, some portion of it might be diverted and used for recreation outside of controlled spiritual settings; and finally, that importation would violate both the US Controlled Substances Act and the 1971 United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances, to which the US is a signatory. Allowing lower-court rulings to stand, Kneedler maintained, would undermine US drug policy. Open that door, he said, and who knows what groups might claim a religious use for drug activity—for example, Rastafarians with marijuana.

In response, Nancy Hollander, the lawyer representing udv, argued that in Brazil, where hoasca is legal and where the udv has been active for decades, and in New Mexico, sacramental consumption of the tea has caused no significant adverse health consequences and has not been diverted to illicit use. Nor has there been any evidence that peyote—used by the much larger (250,000 members) Native American Church—has been diverted to non-religious uses. As for the 1971 UN convention, the lower courts had already found that it does not apply to plants or to infusions, concoctions, or teas made from them. Moreover, the convention expressly permits religious-use exemptions, such as for peyote.

The Supreme Court largely agreed with Hollander. Justice Stephen Breyer noted “a rather rough problem under the First Amendment” and argued that if it was permissible for Congress to make an exception to the Controlled Substances Act for peyote, why not for hoasca Chief Justice John Roberts objected to the government’s “totally categorical” approach, saying it would apply even if a single member of a single udv group consumed a single drop of the tea once a year. Even Justice Antonin Scalia, a conservative who might have been expected to support the federal side, seemed skeptical. It was Scalia who wrote the 1990 opinion that had allowed states to ban tribal use of peyote. That decision was effectively overturned by the Religious Freedom Restoration Act—and the results of the reversal, he suggested, were a demonstration that “you can make an exception without the sky falling.” When Kneedler protested that making such an exception would effectively turn decisions about federal drug laws over to 700 district court judges, Justice David Souter observed, “Isn’t that exactly what the act does”

The Supreme Court rendered its verdict in February, voting unanimously in favour of udv’s position, with one abstention. In his written ruling, Chief Justice Roberts noted, “Everything the Government says about the dmt in hoasca—that, as a Schedule I substance, Congress has determined that it “has a high potential for abuse,’ “has no currently accepted medical use,’ and has “a lack of accepted safety for use…under medical supervision,’ applies in equal measure to the mescaline in peyote, yet both the Executive and Congress itself have decreed an exception from the Controlled Substances Act for Native American religious use of peyote.”

What impact the US decision will have on other jurisdictions remains to be seen. In Canada, the use of ayahuasca remains, at least for now, illegal.

After completing his Ph.D., Jeremy Narby returned home to Switzerland and joined Nouvelle Planète, a Swiss ngo dedicated to promoting bilingual education and securing property rights for South American Indians. At the same time, he started writing a book, seeking to reconcile shamanic wisdom with scientific knowledge, and to explain how plants might, in fact, communicate. He read dozens of books and scholarly articles, made copious notes, and went for long ruminative hikes, but after some months felt no closer to postulating a theory.

It was a footnote in an article by another anthropologist, Michael Harner, that finally provided the spark. Harner had taken ayahuasca with the Conibo Indians in the Amazon in 1961 and, like many others, had been transformed. In his vision, he had seen giant dragon-like creatures, which spoke to him in a kind of thought language. They showed the earth as it had existed before life had formed. Then, thousands of black specks with wings and whale-like bodies descended from outer space. He was told they were embedded within all forms of life, including humans. Harners footnote said, “In retrospect, one could say they were almost like dna, though at the time I had no knowledge of dna.”

dna (deoxyribonucleic acid) is, of course, the language of life itself. Informing every living thing on the planet, every microbe, plant, and animal, it is a miniature coded text that has survived, virtually unchanged, for at least 3.5 billion years. The only difference between a bacterium and a human being, with respect to dna, is the amount of genetic information carried and its sequencing. In an average human being, there are enough strands of dna to cover 125 billion miles—enough to wrap around the planet five million times. Moreover, dna contains coding for an unfathomable amount of genetic data. Think of the largest, most sophisticated data-storage device: dna contains 100 trillion times as much information. A single cell contains more data than all the volumes of the Encyclopdia Britannica put together, yet weighs less than a few thousand millionths of a gram.

Poring over his notes, Narby suddenly had an epiphany: the shape of the dna molecule, discovered by Watson and Crick in 1953, is the double helix, a serpentine form that twists endlessly upon itself as it replicates. It’s like a sinuous ladder, consisting of four chemicals—adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and thymine (T)—that bond repeatedly in pairs (A always with T, C always with G). That same shape, he realized, is precisely the form described by shamans the world over to explain the origins of life on earth. On every continent, from ancient Sumer to Scandinavia, from Amazonia to Australia, creation myths speak of twinned serpents, twirling ladders, twisting ropes, spiralling staircases, intertwined vines, or trees that stretch from heaven to earth, the so-called axis mundi. Even the Old Testament’s patriarch Jacob dreams of a ladder touching heaven “with the angels of God ascending and descending on it.” In Amerindian terms, ladders, ropes, vines, and trees are the means by which shamans ascend to the heavens or descend to earth to communicate with spirits.

Narby was staggered. “It seemed that no one had noticed the possible links between the “myths’ of “primitive peoples’ and molecular biology,” he says. On the contrary, the wisdom of indigenous peoples was typically discounted and their knowledge of pharmacology deemed an accident. But the parallels were striking. Like the serpents of myth, dna is both incredibly long and infinitely small, lives in salt water, is both single and double, and capable of complete transformation while remaining the same.

The ancient Egyptians, Narby notes, used the phrase “provider of attributes” to describe their cosmic serpent. They depicted it as a two-headed snake accompanied by hieroglyphs, which variously signified the concept of one, several, spirit, double vital force, place, wick of twisted flax, and water. They also added an ankh, symbol of the key of life. Similarly, Ashaninca cosmology speaks of the “Great Transformer,” Avreri, who created life on earth, lives in the underworld (the cellular level), in sea water, and adopts the form of a cord or strangler vine. For the Shipibo-Conibo of the Amazon, the earth is embraced by Ronn, a cosmic, amphibious anaconda, which is half-submerged but surrounds all of life. What else could the Egyptians, the Ashaninca, the Shipibo-Conibo, and others have meant by these metaphors if not dna

Slowly, Narby enunciated a thesis—speculative, to be sure, but compelling—that integrated shamanism and microbiology: ayahuasca enables shamans to bring their vision down to cellular levels. The spirits they “see” in altered states of consciousness are photonic resonances or electromagnetic images of dna. Scientists have confirmed that dna does emit light and have compared these emissions to a weak but discernible laser, brightly coloured and three-dimensional. Virtually all research into biophotons, moreover, involves quartz, a stable crystal known for its ability to send and receive electromagnetic waves. dna, too, of course is a crystal. Perhaps, Narby theorized, that’s what shamanic spirits are—light signals, amplified by ayahuasca or other psychoactive substances—that can be read or interpreted for specific information. Perhaps we are, in essence, as mystics have always maintained, beings of light.

To test his hypothesis, in 1999 Narby took three molecular biologists to the Amazon to drink ayahuasca. None had previously consumed a psychoactive plant. Afterward, all said they had been dramatically affected by the experience, that it had altered their way of perceiving themselves and the world. During the sessions, each posed questions about their work and received answers. One involved a new way of thinking about aspects of the human genome. Another related to the proteins that make sperm cells fertile. A third dealt with the ethics of modifying plant genomes. All said they planned to return—and drink again.

It is not easy to challenge the orthodoxies of Western science. One can publish books but they are apt not to be celebrated, reviewed in major newspapers, or discussed on Oprah. Narby’s The Cosmic Serpent and its sequel, Intelligence in Nature: An Inquiry Into Knowledge (published last year), have attracted a cult following but have been otherwise ignored.

Still, the problems Narby articulates remain. If dna is fundamentally a text, can “one presuppose that no intelligence wrote it,” as he asks If humankind is merely the result of eons of random natural selection, what adaptive advantage was gained by embedding the capacity for transcendent hallucination within the brain Do all of us have centres in the brain that respond to mind-altering teas by repeatedly spewing forth visions of jaguars and serpents Or is the brain as much a receiver as a transmitter, tuning in, as the shamans say, to parallel planes of reality, to “television of the forest,” or, alternatively, dna tv Even Benny Shanon, clinging to familiar scientific modalities, writes that “perhaps we have no choice but…[to] consider the possibility that these commonalities reflect patterns exhibited on another, extra-human realm.”

Shanon is not alone in thinking this. During the 1990s, American psychiatrist Rick Strassman conducted the first federally authorized, peer-reviewed research into human hallucinogens in more than two decades, injecting pure dmt into 400 healthy volunteers in a clinical setting. In his subsequent book about the project, dmt: The Spirit Molecule, Strassman acknowledged that the visions his subjects encountered—among them, insect-like intelligences, aliens, angels, demons, imps, elves, dwarves—could not be logically explained by prevalent theories of hallucination, the Freudian unconscious, or Jungian archetypes. In daily life, Strassman concluded, our brains are “tuned to Channel Normal. dmt provides regular and reliable access to other channels. The other planes of existence are always there…transmitting all the time but we cannot perceive them because we are not designed to do so.” Such views, Strassman concedes, are hard to reconcile with the current scientific model, premised on objective reality.

The idea that dna might have been “written” is not, it should be said, creationism by another name. Jeremy Narby is a secular agnostic. His anthropology has more in common with Marx than anything else. When he is not writing books, he is waging battle against the World Bank and big ranchers and land developers in Peru. “Whether out in the cosmos there is one God or many gods—anything is possible,” he says. “The universe is a fabulously complex and weird place and I dont know enough about it.” At the same time, he acknowledges doubts about Darwinian theory and the circularity of its argument—namely, that its conclusion (certain characteristics develop because they are selected by nature) is assured by its premise (nature selects those traits that promote species survival). “Nature is an edifice shot full of intelligence, which most probably did not occur by chance,” Narby says. “I’d sign up for that. Random collision of molecules is not part of my belief system. dna itself seems to be the result of some kind of intelligence—the most miniature language possible but more complex than anything we know. You could not make a more sophisticated language. The entity that came up with it is way beyond something I can understand.”

Considered across the span of human history, mechanistic rationalism, of course, is the new kid on philosophy’s block. As Narby notes, 99 percent of the religious history of Homo sapiens sapiens is animist. “And then along comes rationality and monotheism and it takes 2,000 years, 100 generations, to get chemistry, control of matter, technology, electricity, etc. The price we paid was cutting ourselves off from quite a few things—nature, the feminine, our own visions, dreams. Suddenly we’re surrounded by all these objects and we’ve lost the sacred and connections to other species. But we know it. So we correct.”

Well, perhaps. As the US Justice Departments case against União de Vegetal illustrates, governments are prepared to go to great expense and length to enforce blanket prohibitions on the use of psychotropic drugs. They cite the risks of use and make authorization to conduct new research difficult to arrange. The scientific community remains utterly dismissive of such notions as intelligent dna or alternate channels of reality. But how can science assume dna is a mere chemical when, as Narby notes, it does not even understand the brain, the seat of our own consciousness, built according to the instructions laid out in our dna “How could nature not be conscious if our own consciousness is produced by nature” he writes. The profound mysteries of human life—our consciousness, our origins, why we’re here at all—remain.