Leona was awoken by a scratching noise from her ceiling. Furtive rasping claws. Scratch, scratch scratch. She sat up in bed and fixed her eyes on the ceiling, straining to decipher the overhead activity. The landlord had assured her on several occasions that the property was rodent-free, but she had little doubt that the activity was rodent-related. Yes, it was a rodent problem. She did not know what type of rodent, but she had a strong suspicion that they were rats. Judging from their movements. Slow and conspiratorial.

About two weeks later the rodent problem took a turn for the worse. Leona’s landlord, in whom she had placed all hope for a swift solution, refused to return to her apartment or to look further into the problem. He had visited her apartment three times since the first morning, visits that coincided with periods of absolute silence from the ceiling. None of the other tenants, he told her, had mentioned noises. How would they have made it up to her apartment without disturbing anyone else?

After a night of unusually intense activity, Leona made a fourth call to the landlord, who told her that he did not feel comfortable making another visit. She stared at the telephone and said, in the landlord’s slow, patronizing voice, I do not feel comfortable.

Leona knocked with a broom against the ceiling. There is nothing more disgusting than a rat, she said. They were revolting creatures, but she could not stop thinking about them. It was not their stiff tails or their jagged teeth that troubled Leona, it was the idea of their nests. She pictured a star-shaped network of domes connected by damp tunnels. A nest at each of the star’s points, criss-crossed by tunnels, potato-width, one rat at a time.

They had brought dampness into her ceiling. Dampness and building materials. Like the rodents themselves, the nests were surely multiplying, so that Leona felt herself surrounded not with one or two nests but with dozens of nests, each thronging with a new generation of rats — tiny, sightless, unknowing. Clawless and mute, they lay in wait; they would complete the work of their progenitors. She listened dolefully to the chatter of her ceiling, tracking their fitful migrations. Their activities, she noticed, seemed to be concentrated above her bed. I did not ask for this, Leona said.

Sensing that the network was expanding, Leona telephoned her sister. They had not spoken for several months. She carried the telephone to her bed and crawled under the sheets. She was determined not to raise her voice. It was all too easy to raise her voice. Her sister brought this out in her. Rational Nancy. Failure-to-respond Nancy.

“I don’t think you understand. I don’t think you realize the scope of the problem.”

Leona paused, waiting for a response. Her sister did not understand. She had not, for one thing, considered the dampness. Leona pulled her legs under her stomach and adjusted her position in the bed, forming a sort of miniature tent.

“Here you are, now. Nancy, are you listening? Listen. Where do they urinate? Can you tell me that?”

The beseeching edge dropped from Leona’s voice. She seemed to have settled on a definitive point of view.

“Where do they do it, Nancy? I want you to tell me where they urinate?”

She pressed the receiver against her ear, waiting. No response. Nancy had no idea. Leona knew how this looked to her sister. She was familiar, in her own way, with both sides of the exchange: the reliable side, the unreliable side. She clung to the hopelessness of her appeal, as if it could buoy her up.

“Not in the dens,” Leona announced. “That goes against their instincts. They urinate in the tunnels. That’s how they build. They use the dampness.”

A week later a small, potato-shaped stain appeared on her ceiling. One day the ceiling was unstained, the next day the stain was there.

“Jumping Jesus!” Leona yelled. “What are they up to?”

She pictured the damp tunnels, the accumulation of urine, the spill-off area.

“What is happening to my world?”

The stain’s borders were poorly defined. Someone less familiar with the ceiling would have assumed that it was a smudge, but it was clear to Leona that it was no smudge.

Occasionally Leona had guests.

“You think I am imagining this,” she said to her guests. “Come into the bedroom. We’ll see who’s imagining.”

Leona stood in the middle of the room, pointing at the ceiling. There was a small stain on the ceiling, more or less oval in shape, directly above her bed.

“It’s expanding,” she said.

Within a week the stain had tripled in size and begun to show faint signs of differentiation. Leona wondered at first whether it might be a tiny reproduction of her bed, but decided that the edges were too uneven. During the third week she was convinced that it was her own shadowy reflection, but the resemblance declined with each passing day. It was a human shape, unmistakably, but not her own.

“What delicate feet you have. I’ve never seen such feet!”

She was pleased by the sound of her voice drifting languidly through her bedroom. Her attitude toward the stain was changing. She did not deny the relationship between the stain and the rodents. No, she did not deny the unsavoury provenance of the shape but she felt that it was okay, that it was a natural part of her life.

“Where do you come from, my lonely one? Why have you chosen me?”

At other times she was plagued by doubts.

“Maybe I am only imagining,” she said. “Maybe it is my imagination, my own desire to be chosen.”

At such moments she grimly embraced her isolation.

“I have not been chosen at all,” she said. “Oh God, I will never be chosen.”

When they entered her dreams, which they often did, the rats were solicitous and compliant. In contrast to the rodents in her ceiling, the rats in her dreams were not in any sense against Leona. They seemed, on the contrary, viewpoint, a sprawling rodent extension of her dream personality. This intimacy was comforting to the sleeping Leona, but deeply unnerving to the waking Leona.

In her relations with the dream rats Leona occupied the position of a conductor or circus master. She waved her arms and the rodents scattered, rolling backward in a single giant wave. She folded her arms and they scurried toward her, assembling eagerly at her feet. More remarkably still, they were able to speak. This verbal capacity seemed quite natural to Leona but what did not seem natural was that the rats spoke in unison, forming a single collective voice. It seemed wrong that the rats, sometimes two or three hundred of them, all spoke at once — simultaneously hinging and unhinging their rodent jaws.

“Love, love, love,” they whispered, exposing their cracked, brown-yellow teeth.

They were invariably reassuring, offering sympathy and encouragement, but this did not help. The giant chorus gathered before her:

“We agree with you Leona; we know what you mean.”

It was in the hallway outside her apartment, six weeks after the stain first appeared, that Leona realized what was happening. This was no anonymous visitor, no mysterious apparition. It was all too familiar, all too familiar and all too repulsive; it was Annunciation George.

“Fuck me,” she said. “It’s Annunciation George. How could I have missed it? He was right before my eyes, not ten feet away from me this whole time. Fucking Annunciation George. I can’t believe it.”

Leona nearly collapsed. She tried to move, to open the door, but her limbs stiffened and locked into place. Blood collected in her feet, ankles, unbending knees; it resumed an insidious gravitational agreement. She made a second attempt to press forward, a third attempt. It was not this but some other, involuntary action that carried her into her apartment. It is easy to see what you want, Leona. Easy. She opened her door and stumbled into her apartment, resolving not to leave until she had dealt with the rodents, with the rodents themselves and the rodent agenda, which had revealed its ugly face.

Annunciation George lived across the hall from Leona. He had moved into the building about three months ago. He was a Christian fundamentalist who, still fresh from his conversion, restlessly advertised his spiritual rebirth. She had first met him in the elevator, where, discovering that they lived on the same floor, he had thrust forth an alarmingly damp hand and sputtered, “I’m George Howard and I’ve been reborn.”

Leona gazed warily at their interlocked hands. “I see,” she said. “Well, better luck next time.” George swung his arms in an exaggerated circle and clasped his hands to his hips, projecting his elbows. “Next time,” he barked. “I like that, I really do!” Then, shifting his hips slightly, as if preparing for a fitness demonstration, he produced the most menacing smile Leona had ever seen. The lips of punchdrunk astronauts, locked into rocket simulators, circling at unearthly speeds in egg-shaped capsules. When the elevator door opened, Leona walked rapidly toward her apartment, glancing backward repeatedly to ensure that she wasn’t being followed.

Leona’s first impression of George Howard was that he should have been bald. Everything would have been better for him if he had been bald. He was one of those men who should have been bald but wasn’t.

Were the rodents communicating with Leona or was George communicating with Leona through the rodents? These were not the only choices. Someone else might have deployed the rodents as mediators. Somewhere outside the building, entirely unknown to the occupants, someone might have said, I send you, my substitutes, I send you. Which would explain the corporate character of the intruders. Why had they spoken with one voice? They were not speaking for themselves. They did not possess separate voices. It was as if she had spent the evening at a ventriloquist’s performance and fallen for the dummy. At last, pushing her way through the crowds and trotting backstage, knocking gingerly on backstage doors, one by one, until she found the ventriloquist. Where is he? she gasped. Where is he? And then to find the slumped wooden actor, breathless and stupid, in the corner of the room. He was so real, so true to life. With the ventriloquist doubled over by the door. Ha, I mean. Did ya really think? he said. I mean, ha, ho ho, did you? But perhaps she hadn’t thought him real, or exactly real.

Leona rummaged through several cupboards before she found the unopened bottle of gin. She poured a full glass and sat down on the couch. She felt suddenly that she was not so different from an animal. The more she looked at her hands, wrapped awkwardly around the glass, the more they looked like monkey hands or, worse, the groping paws or fumbling hoofs of a barnyard animal. She sloshed back the rest of the gin and refilled her glass.

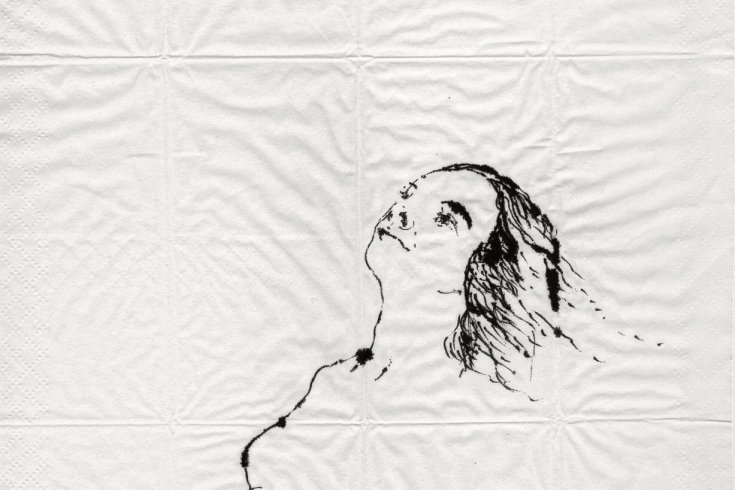

After her third glass she became entranced with the physical properties of the gin. Still holding her drink with both hands, she lifted the glass to her lips and slowly tilted both her head and the glass. Her head swung back, drowsy and deliberate, like a sleepy hinged vault, forgotten by living bankers and living investors. The transparency of the liquid was mesmerizing. At first she’d found the gin medicinal but now she discerned the hidden berries and shimmering meadows. Transparent, she said. Trans-parent, trans-parent.

She rolled her head back and forth, wistfully surveying the missed opportunities that crowded, like thousands of ghostly commuters, around her lonely mornings and her lonely afternoons. There is so much in this world that I haven’t seen, Leona said. I have seen practically nothing. Why had she left this gin in the cupboard? Why did she not take possession of her own experiences? She walked unsteadily to the kitchen. I have been living half a life. I have been afraid to take steps.

Look at me with my monkey hands, donkey hands. Leona poured the last of the gin into her glass, but instead of sitting on the couch she sat on the kitchen floor. What if they find me like this? The scene unfolded in her mind. A man is standing over her in a white and yellow jumpsuit. At first she doesn’t recognize the markings on the jumper, the uniform of the paramedic. His face is blurred. What if they find me? She pushed her glass along the floor and made her way to the living room on her hands and knees. How often she had told herself, do not let yourself feel this, do not let yourself feel that. She shuffled forward on her hands and knees then planted her arms on the sofa and raised herself to her feet. She lurched dangerously, balancing herself against coffee tables and bookshelves. I have my desires, she said. Animal desires, barnyard desires.

Look inside and you will see you are the only one for me. One for me, one for me, you are the only one for me. Look inside and you will see.

Leona tottered into the bedroom and dragged her armchair onto the bed. George loomed above her, more inscrutable and alluring than ever. The thoughts I have of you. She mounted the chair, buried her head between her legs against the swirling elements, and then, in a single continuous action, thrust her arm to the ceiling.

George Howard was a substantial but by no means obese man. It was the distribution of his weight and not his weight as such that singled him out among the bulky. He possessed that physiognomic rarity, the masculine variant of the hourglass figure. Above and below his delicate waist, the waist of an acrobat or a chorus girl, George Howard was uniformly plump. At one graceful point, the midpoint, his body contracted into the body of another, much slimmer man, perhaps the body of a former George, the George of years ago. What remained of this man? His waist.

Woo, Leona said, Woo–oo. She tapped her hand against the ceiling. It was time I’d taken a lover, you said. Time for me, you said. I did not blame you; I knew something of love. Took a lover. Took–a–lo–ver. She traced a lovesick finger over the muted shadow. It was not a continuous outline, for it left something to the imagination. This was not the blustering resemblance of the photographer, the vulgarian’s vulgarian.

In her dream she sees a gentleman in a white and yellow jumpsuit. He has a broad athletic face, neatly combed black hair, a black moustache, and the voice of George Howard. He kneels over her, lays a hand on her forehead, and whispers in her ear: The animals, you know, when they crawl through the snow, sing softly of the snow, the only words they know, ding-dong, ding-dong.

The hallway was far brighter than she remembered. This wasn’t helped by her shiny yellow dress. She realized, too late, that it was entirely too bright — asteroid bright. The salesman had deceived her, concentrating on the garment’s snug fit and promising new, fantastic results. She would knock them over at the Christmas party. Bowl them over. He had switched on a cassette player when she was looking at herself in the mirror. Romance was in the air, romance and adventure; she fell for the hoax. Soaring avowals of love swept through the store, dancing over the humdrum racks, animating fancy skirts and fancy dresses, animating sequined blouses. I am a woman in love and I’ll do anything to get you into my world. Knock those pins, he said. Bowl ‘em over, knock them down. What had she done?

With her eyes squinting and her hands raised to her forehead, she knocked on the door.

George was white as a sheet. His face, poking out above a brown housecoat, seemed to absorb the fluorescent light of the hallway. Like a glowing and suddenly unanchored buoy, somewhere in the middle of the ocean: a spar buoy, a gong buoy, or a whistle buoy. The single word George was sewn into the pocket of his housecoat, red against brown.

“I don’t expect you to understand,” Leona said.

“Pardon me,” said George.

“I don’t expect you to understand my feelings. We rarely do understand one another, as people I mean. As we should understand each other. We just keep waiting, don’t we? I mean, that’s what ends up happening. You’d think we might get something like that from our families but I don’t think we do. I don’t think we ever do get it, do we?”

George stepped back from the door. Leona took the opportunity to advance a few steps into his apartment.

“I don’t mean to barge in.

“You get the impression sometimes that you’re just waiting to start your life. Like maybe it hasn’t really started. I sometimes think that, that all my life I’ve been wearing one of those horrible signs from dental offices: Back in ten minutes. Like I’ve been wearing one of those signs for years and years and no one’s ever come back to take it off.

“The truth is, nobody is ever paying attention, really paying attention. Like the way that people say to you, sometimes two or three times in one day, How are you? And when you decide that you want to be honest for a change and you don’t want to just snap at each other like robots, you know, so you tell the person that actually things haven’t been going well at all or that you think you’re just on the verge, like you can’t stand it anymore, and nine times out of ten that person is going to look at you and say they know just how you feel. Oh yes, I know how you feel!

“If you think of that, the idea that you know how the person feels, that you actually know how they feel, you’re going to stop for a moment and you’re going to realize that it’s a very profound thing. You’re not going to say, like you were some kind of talking robot and you’d run into another talking robot and you were both programmed to just say these totally senseless things, Yes, I know how you feel. Because what is that, knowing how they feel? That’s probably the most profound thing, if you stop to think about it.”

Leona was beginning to suspect that the very thing she had been describing was happening before her, that George Howard didn’t understand her and that he didn’t even have the option of pretending that he understood her by saying that he knew how she felt or that he knew what she meant because she had basically ruled out that option. His facial expression did not suggest recognition or concern, which might have worked to her advantage, but alarm. He was fumbling with the collar of his bathrobe, pulling it tighter and tighter around his neck, to the point where he was maybe in danger of cutting off the circulation to his head.

The fact was that George knew nothing of the stain on Leona’s ceiling or of the intimacy that had developed behind the closed door of her apartment. Leona apologized and retreated hurriedly into the hallway.