I made a girlfriend a while ago.

String, wax, some chemicals.

She was sassy. I made her in the morning and when I got home from work that day I asked if she would like me to order pizza for dinner.

“What do I want pizza for?”

She had moxie.

First thing I said to her, actually, was, “What are we going to call you?”

She said she didn’t care.

“You’ve got to have a name,” I said.

“So?”

“So you look like a Jackie.”

“So call me Jackie,” she said. “I’ll be me, you’ll call me Jackie, everyone will be happy.”

I went to work, came home and suggested the pizza— those were our first two conversations. And that night was our first date.

“If not pizza, what?”

“Thai. I feel like going for Thai,” she said.

I dressed her in a different outfit and we walked to Thai One On.

“I like the name,” I said.

“These shoes are too tight.”

“Sorry.”

“Yeah.”

“I like the name of the restaurant.”

“I don’t.”

“No?”

“I don’t like puns. Men like puns. You don’t see women playing with words.”

“That’s true,” I said.

She was pretty quiet through dinner. I talked for both of us and ate most of the food.

“Sorry I never gave you much of an appetite.”

“Yeah,” she said.

The walk home was quiet as well. We held hands, watched other couples. “It’s hot,” she said. She was always sweating.

“Do you want to get a cold drink, or should we just go home?”

“Both,” she said. “I can’t decide.”

“Let’s get a cold drink at home.”

“Yeah.”

We carried on.

A lot of other couples we saw seemed happy. I looked at the women’s faces, tried to catch their eyes without their boyfriends noticing. I looked at Jackie sometimes to see where she was looking, but I couldn’t tell. She was inscrutable.

When we got home I decided to forget about the cold drink and take her straight to bed. The sex was incredible.

She had one green and one hazel eye.

“So what is it you do?” she asked me the next morning.

“I’m a civil engineer. These eggs are great.” She made excellent breakfasts. “I’m a civil engineer, but I’ve also been a professional referee—soccer—for almost eight years.”

I took her to a game that weekend. It had turned cold, so I dressed her in an oilskin coat, which made her shoulders look small and cute. I made some controversial calls that game. My mind was elsewhere.

When I found her in the stands after the game, she was sipping a hot chocolate. I hadn’t given her any money so I wondered how she got it.

“I have my ways,” she said.

She looked so pretty.

For a while she came to all my games. “A referee’s wife should never cheer, one way or the other,” I told her. I think she was happy with that. Anyway, “Wife?” she said. “Wife?” and she wiggled her bare ring finger.

Everyone at work wanted to meet her.

“So when do we meet your Jackie? Where are you hiding the beautiful Jackie?”

“Ha ha,” I said.

I like to keep my private life separate from work.

She took me out of myself. When I wasn’t refereeing on a weekend she would say, “Let’s go away.” She had all the ideas—weekends at wineries, hang-gliding. I just went along and found new abilities within myself.

“I’m starting to be able to taste the difference between wines.”

“Huh,” she said.

It was getting expensive, of course. I wasn’t pining for my simple life alone, but my credit cards were getting full.

“Why don’t you get a job?” I asked her.

“I’m trying to figure out what I want to do. Not all of us have engineering degrees.”

She had such an elegant, confident way of holding a martini—she looked fragile, but you could bump into her, hard, and she wouldn’t spill a drop.

“I think you should just get a job,” I said.

Next thing I knew she was getting up long before me, making my breakfast, and slipping out to a job she had found in the industrial park.

“Imovax,” she said.

“What do they do?”

“Technology.”

“What kind?”

“I’ve got to go or I’ll be late.”

“I’m proud of you!”

She told stories about work at first, long ones that were miracles of pointlessness. I couldn’t keep track of all the names, and I just smiled while her dinner got cold in front of her.

She got quite tired after her days at work. The sex was still incredible—I did such a good job on her body—but sometimes she had trouble staying awake afterward. Sometimes she read me stories.

“What’s this word here?”

“Anhedonia,” I said.

“What does that mean?”

“Sorry I gave you a small vocabulary.”

“Yeah.”

We went away one weekend to a retreat, one in the mountains where you meditate and can’t talk to anyone for forty-eight hours. She loved it. I found it difficult. I wanted to know what she was thinking all the time. Did she think of me often? They kept us in separate rooms so we really couldn’t speak and I became annoyed with the whole arrangement. I was paying for imprisonment in the name of enlightenment and achieving alienation. That’s what I wrote on the Comments form before I left. And Jackie maintained her silence all the way home in the car.

“You can stop now,” I said. “You can talk now.”

But she looked completely at peace. I wanted to pinch her to bring her frown back. She had such a sweet little frown, like a child’s, which you couldn’t take seriously but had to. But her brow stayed smooth and she didn’t say a word to me until Monday night, when she told more stories about work.

“Don’t you want to know how my day was?” I asked her.

“I know how your day was.”

“How?”

“I have my ways.”

“How?”

“Let’s just say I do.”

She was coquettish that night. Things were looking up again.

“You’re a mystery to me,” I said. She knew things about me that I’m sure I never told her.

“Remember when you were twenty?” she said.

“Yes.”

“And you met that girl at that bar, never got her name, talked all night, and said that one thing which made her eyes open wide like a train was howling toward her?”

“Yes.”

“And then last year you lost the company that municipal contract by budgeting for unnecessarily expensive and dated materials?”

“Yes.”

“Isn’t that a telling diminution of potency?”

“Who taught you those words?”

“I don’t know.”

“I’m so proud of you.”

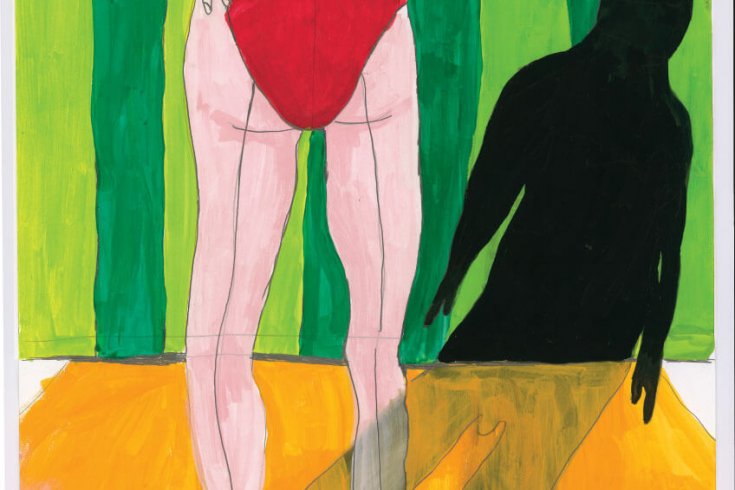

She had a different set of lingerie for every day at the office. Red, black, flesh-coloured: you name it, she owned it. I wanted to tell her I loved her. I could sense her deliberately retreating sometimes. She was guarded from the beginning—someone who always wore sunblock, and I was an inevitable sunburn. She couldn’t believe she had me.

“You can’t get rid of a sunburn,” I told her.

“I know.”

“It just settles into a tan.”

“What are you talking about?”

“What do you do for lunch when you’re at work?”

“I eat at my desk.”

“Maybe I’ll meet you for lunch sometimes.”

“If you like.”

I thought I would surprise her. I went to the industrial park one day around noon, driving slowly, looking for signs. I couldn’t see any for Imovax so I got out of the car and wandered. There were too many little businesses in there. All those letters in all those names, and all the little people behind them. My eyes got an itchy feeling.

“What’s the address of Imovax, Jackie? Let’s say someone wants to send you flowers.”

“Two-One-A Industrial Avenue.”

“Got it.”

I went to 21A Industrial Avenue. Sportflex 2000. They sold gym equipment.

“It is Imovax, isn’t it Jackie?”

“What is?”

“The name of your company.”

“Imovex.”

“Right.”

“I want a tattoo.”

“A tattoo?”

“On my hip. Here.”

“Really?”

“Kiss me there.”

I gave her a tattoo.

There was no directory of the whole industrial park—just sections. I did a Google search for Imovex and found their website. They created and distributed Linux-based applications. I clicked on their Contact Us tab to get their address, but my computer went down.

“Two-One-A Industrial Avenue, right Jackie?”

“Two-One-Eight. What is it with men? The hearing goes, the confidence goes…”

I wrote down the address. Things were getting busy at work, so I couldn’t spare any lunch hours.

Then the playoffs began. Jackie really enjoyed the playoffs, although she never said so. She said the playoffs at least suggested there was a point to it all. The weather was much colder, so I made her scarves and mittens, sweaters to beef up the strength of that adorable oilskin coat.

I saw her from the pitch talking to people in the stands. I assumed she was telling them about me, why she was there, her relationship with me. I straightened my shoulders, made some excellent calls, smiled and laughed with the line judges. Refereeing has kept me fit.

“Who were those people?”

“Which people?”

“I saw you talking to people in the stands.”

“I thought you were refereeing.”

“A good referee can take it all in.”

“Lesley and Lindsay.”

“Which one was the girl?”

“Lindsay.”

“Were they nice?”

She had a very mischievous look.

“Watch where you’re driving!”

“Were they nice?”

“Sure they were nice. They were both coming on to me.”

“Even Lesley?”

“Lesley was the man.”

“Even Lindsay?”

“Both of them.”

We had a long talk about becoming swingers. Lesley and Lindsay had invited her to a party, a regular event. She could bring me if she wanted. I said we weren’t getting involved in any swinging until I had a closer look at the girl, Lindsay.

“She’s not prettier than I am.”

“Don’t be jealous,” I said.

And I also told her that we were not getting involved unless she was slightly revolted by the men.

“I’m always slightly revolted,” she said.

“Anyway, let’s talk about it,” and I put the matter to rest for a while. She took one shoe off and put her bare foot on the dashboard of my car. A dead moth was on its back near her painted little toe.

“You are such a bad driver,” she said.

“Muffin?” I said.

“What?”

“We just passed a café,” I said. “Shall we get a muffin?”

“A muffin?”

“Yes.”

“You know I hate muffins.”

And I did know perfectly well that she did not like muffins, but nothing got me wilder than seeing her mouth say the word, her lips kissing each other, a flash of teeth in the middle, her secret tongue touching in against her palate. I drove her home quickly and kept her busy until I was exhausted.

When I finally found and dialed the number of Imovex, I met the voice of someone I thought I knew by sight.

“Imovex, good morning, this is Lesley speaking.”

I paused for a moment. “Lesley, eh?”

“Yes.”

“Lesley the man.”

“This is Lesley.”

I paused again. “Tell me, Lesley, are you a soccer fan?”

He then paused for a while himself. Both of our minds were racing. “I beg your pardon?”

“It seems the playoffs are heating up,” I said, and we both hung up at the same time.

Jackie was home late that night, a growing habit that was beginning to annoy me. I didn’t say anything. I just watched her as she cooked. She kept her back toward me. The shape of her. All the languages of the world, searching over time for clear communication, breathless connection, and all they ever needed was a letter shaped like Jackie. I moved closer to her.

“Tell me what you know about Linux, Jackie.”

“I don’t know anyone by that name.”

“It’s like a language.”

“I don’t know it.”

“It’s an operating system.”

“Well, all I know is what you know. You know that.”

“Well, you’ve learned a lot since I made you. Tell me what it is you do at Imovex again.”

“You know, filing, talking, gossip. I can’t cook with your hands squeezing my shoulders like that.”

“I’m massaging you.”

“You’re suppressing me. Am I too tall for you?”

“No.”

“So cut it out. I’m cooking.”

“So what did you do at work today, for example?”

“I don’t know. I deleted things.”

“Yes?”

“Mailed things.”

“Yes.”

“I oversaw the rollout of a new digital signature process.”

“Really?”

“So I’m tired.”

“So how do you know . . . You must know that your company specializes in Linux-based applications.”

“There are some people in the company who know some things, other people who know other things. I can’t know everything. I just get along.”

“I bet.”

“Meaning?”

“Did you get along with Lesley today?”

“Who?”

“You know who. The guy who answers the phones.”

“Everybody answers the phones.”

“What?”

“That’s the company’s philosophy. Everybody should answer the phone if they’re free.”

“Sure.”

“Everybody can do anything. That’s the philosophy. How do you think I worked my way up?”

“OK, sure. But you know Lesley.”

“No. I don’t.”

“How many people work there?”

“Five hundred and eighty.”

“What?”

“Hearing troubles?”

“Well, here’s the thing, Jackie: the semifinals are on this weekend, and I’ll be taking in the whole game.”

“Great! And after you recover your senses, here’s your dinner.”

“Aren’t you eating?”

“I’m going to bed.”

“You just got home.”

“I’m tired.”

“I’ll wake you up when I’ve finished eating.”

“I know.”

So I tested her story the next day.

“Imovex, good morning, this is Carole speaking.”

And the day after that.

“Imovex. Jack Blondge.”

“Blondge?”

“Speaking.”

“What kind of a name is Blondge?”

“Who is this?”

“I’m looking for Jackie.”

“Jackie who?”

“Never mind.”

At the semifinal game my head was spinning. It was always an honour to referee a semifinal. (I had been invited to watch the final from the pitch-level seats owned by the Referees Organization. I hadn’t decided whether to invite Jackie.) But the honour and grandeur of the game slipped away.

When I blew the starting whistle I felt as if I awakened every unknown evil like bats in a cave. It was the nastiest game I had ever refereed. I sent a winger off for biting. Then I sent off the opposite winger on the opposite team for diving in the box. With those two gone it was as if I had disturbed whatever equilibrium remained. We all started spinning in a centrifuge, everyone forced together. I couldn’t see where I was, couldn’t remove myself, and I started thinking about Jackie in the stands, a crowd of swingers pawing her, putting their tongues in her ears.

The ball was kicked in my face and my nose started bleeding. I couldn’t stop the blood. No one could stop the blood.

“Everyone was laughing at you,” Jackie said.

A substitute referee had never replaced me in the history of my career. “I am seriously thinking of not inviting you to the final, Jackie.”

“Sad,” she said.

And what would we do? Would something come back or would we both spin closer and closer until one of us got hurt?

I found myself poised above her sometimes at night, in bed, a pillow in my hands, a silent end in mind. Her breath was so slight that I put my ear to her perfect little nose, to make sure she was breathing, and whenever I heard a sound of life it was more a message than a breath. You can’t, you won’t, you need me.

I expected to wake up sometimes to find her poised above me in exactly the same way, but I only found her sitting up and staring out the window.

“I feel hollow.”

“You look so pretty.”

“I feel hollow. Am I going to change?”

“I don’t know. Go to sleep.”

“You go to sleep.”

And soon she developed what we called her smudge. It was an erasure, really. I had suspected something like this when I first made her. Part of her simply disappeared—on her left arm, just below her shoulder, a piece about the size of a mandarin orange. You couldn’t tell unless you saw her naked, but you could definitely see objects behind her where flesh used to be in the way. I was casual about it when I first saw it. “You’ve got a smudge there.”

“What?”

“Just below your shoulder. You’ve smudged away a bit.”

“Jesus!”

She was alarmed at first. And when she looked in the bathroom mirror she went crazy.

“You did this to me! You!” She was panicking and rubbing at the mirror. It really did look like a flaw in the glass or a bit of steam that couldn’t be rubbed away. She started touching her breasts, ears, hair, lips, in a way I had never seen. Clutching. No more sense of ownership.

I left her in the bathroom and sat on the edge of the bed. After a while, I got some of her clothes together and we went outside for a walk. It was one of those cold pale Sundays just before winter, when every park bench in the city holds couples looking away from each other. Tears, disease, abortion, betrayal, I can’t believe you’re saying this.

She put her arm around me and we walked for a long time, saying nothing. Eventually we commented on little things: “That house is for sale again,” “That crow has meat in its beak.” I bought her a hot chocolate. By the time we got home we were remote, our minds elsewhere, but closer than we had ever been. After we turned out the lights by the bed I leaned toward her and whispered, “It’s just a smudge.” She got up and went to the bathroom and spent most of the night in there weeping.

Then she changed completely. I expected a sour wind to blow through our lives, a smell of sickness when I walked through the door. If we managed not to voice or show our worry, I still expected our actions, everything we said, to seem like wartime entertainment. But she became a genuinely positive presence. She filled the house with flowers, which she said, every day, were for me.

It was a nice gesture. “You don’t have to do that,” I said. “You’re the sick one.”

“I’m not sick.”

“That’s true. It’s just a smudge.”

But positive change aside, after a couple of weeks she came and sat on my lap and asked if I could fix her.

“No.”

“Why not?”

“I can’t.”

And that was the end of it, as far as I was concerned.

“Imovex, good morning, this is Tim.”

“Hi, Tim.”

“Hi.”

“Do you know who this is?”

“No. Todd?”

“Wrong, Tim. I’m watching you. I’m watching all of you.”

With her renewed vigour, her positive attitude, her complete disregard of her affliction and her acceptance of my unwillingness to heal her, Jackie spent more time at work. Fourteen-hour days became commonplace. She wouldn’t come to the soccer final, said she had to work.

So I grew more curious about Imovex. The company had started four years ago with thirty-two employees and became what it is today, according to its website, “by acknowledging that blood is mere technology.” The history of the company, click here, left me wondering what my Jackie had got herself into.

I’m Tom Shaw, it read, and I founded this company to keep the fury of rabies at bay. Rabies in our software. Rabies in our soul.

I woke Jackie up in the middle of the night and asked her what she knew of the world. “Madness, cheats, fraudulent needs, betrayal, dubious claims of loyalty and honour. Do you know anything about these things?” I asked her.

“Yes.”

“Do you?”

“I don’t know.”

“Tell me about Tom Shaw.”

“Let me sleep . . . Owwuh!”

(I pinched her.)

“Tell me about Tom Shaw. Stop being coy.”

“Tom Shaw founded the company.”

“Right.”

“He’s a brilliant man.”

“Yes?”

“He cares for all of us.”

“Does he? Even me?”

“You know? I’m beginning to realize that no matter how old a man gets, his sense of humour will always be boyish.”

“Well, I’ve got a quote here . . . ”

“Don’t turn on the light!”

“I’ve got a quote here from your brilliant Tom Shaw that worries me. Imovax, it says. Imovax, the legendary rabies drug, was the cure that could have been. Imovex, the company: the cure that always will. Now, what does that mean, Jackie?”

“I don’t know.”

“Why does he go on about rabies all the time, when he’s running a software company?”

“A raccoon killed his wife.”

“What?” It was hard not to smile.

“There. See what I mean? You’re a middle-aged man. You’re bald. You look grown-up, but you laugh when I say someone’s wife died, just because a raccoon was involved. A raccoon makes it funny.”

“It does make it funny.”

“Do you have any idea how tired I am?”

“But what does the company do? Just help me understand. What does that sentence mean — Imovex, the company: the cure that always will? The grammar of it.”

Jackie got out of bed, picked up her pillow, and said she was going to sleep on the couch.

“I’m just worried about you,” I told her.

I found out more about Tom Shaw through Google. There were several articles. Some of them called him mercurial. He had been an employee of Microsoft, involved in some sort of initiative with India that failed to interest me. While he was away on one of his many trips, his wife, staying with family in Virginia, was bitten by a rabid raccoon when she took out the garbage one evening. The vaccine (Imovax) was not given to her in time, and she died before Tom Shaw returned from his trip.

Predictable reclusiveness followed, including resignation from his job, and when he returned to the world he began a campaign against the “deliberate obsolescence and vulnerabilities of Microsoft.” “I know for a fact,” he was quoted as saying, “that their platforms and applications are not made to last. Viruses will always overcome them.”

He embraced open-source technologies, founded his company with a name similar to that of the drug that could have saved his wife. “I will never sell a product that my customers cannot fix themselves,” he said in a press release. “And I will only sell products that never need fixing.”

His products are “solutions” and “applications”—these words that everyone is selling these days. I couldn’t get a sense of what he was solving. Most of the articles I found on the Internet were about the man rather than the company. One site, called ITBachelor.com, suggested he was desirable. “Net Worth + Conscience = Tom Shaw.” The Internet is a vulgar little funhouse.

I did a Google search for myself and saw a nice picture of me at a university reunion which was held locally last year.

I looked into rabies in Virginia and discovered that the raccoon population was probably infected by animals introduced by hunters to improve their sport.

I learned that the second phase of rabies is the furious phase, when teeth are bared, saliva blooms, and the infected lunge at everything. I tried to imagine Jackie like that. I wanted to ignore her, starve her, dress her in deepest red, take her to dinner, see if there was any real difference between our kisses and our bites.

“Good evening, Imovex, this is Andrew.”

“Can I speak to Jackie please?”

“Jackie who?”

“Never mind.”

I wasn’t sure that Jackie ever fully appreciated what it was I did for a living. She was spending fourteen hours a day at the lap of Tom Shaw learning about “solutions” and “applications.” “What about bridges? ” I wanted to ask her. Engineers have been building solutions for thousands of years. I, personally, specialize in the uses of concrete. What has broader application than concrete? Let’s say Tom Shaw was commissioned by the municipality to consult on a series of administrative buildings to find the lowest construction costs. Would he know that autoclaved aerated concrete could be used to save insulation costs?

“Well, you yourself didn’t know that, and you lost that contract for your company,” Jackie said.

“But I know it now, Jackie. And in the future, when called upon to build schools or what have you, I can recommend that concrete. And I can assure you that nothing your Tom Shaw can create will ever have half the importance of a substance that keeps children warm as they learn.”

“I don’t know what to say,” she said.

“Well, I appreciate the need for technology, and I’m not about to pooh-pooh the importance of computers. And as for open-source technology…”

“Can you just turn the light out?”

“I’m just saying, you know, let your friend Tom Shaw know that I realize his work is important, but he has to get some perspective.”

“What makes you think I’m in regular contact with Tom Shaw?”

“I know you better than anyone.”

“Go to sleep.”

That night, and for several other nights, I again came close to smothering her with my pillow. Her breathing had changed, grown more powerful. The pillow felt too light.

Next thing I knew she was packing for a business trip.

“Barbados?”

“Yes.”

“What kind of a business trip takes you to Barbados?”

“You’ll see. Pass me my hat.”

“Where did you get that hat?”

I was left alone for a week. I had thought of taking a week off and flying down to surprise her, but work was too busy. Years ago I had travelled to Barbados on my own, so I at least knew what sort of landscape to imagine her in. She would probably spend her days on the calm west coast, do a bit of snorkelling. At night she would go to the Ship Inn, and a man would come up to her and say, “I like the name of this place.” She would ignore him. He would wonder whether Ship Inn was some sort of pun or double entendre or something that threatened to mean more than it actually did. He would retreat to his table and wonder whether he could bear another holiday alone.

She had left with no further explanation, and I spent the week not only wondering what the purpose of the trip really was, but also whether she would really come back to me. Tom Shaw probably had a yacht down there.

When she came home looking tanned and impossible, I thought about attacking her somehow, verbally, violently, proving to her that all she could provoke in me was sexual disdain, not need. But I stayed on the couch, drinking Coke with lemon.

“I thought you might be meeting me at the airport,” she said.

“You never told me when you were arriving. You have to give someone flight details if you want him to pick you up.”

“I didn’t know that.”

“Well, now you do.” An ice cube from my Coke raced down my throat.

She went toward her luggage, saying, “I’ve got a little something for your Coke, actually,” and she fetched a bottle of Cockspur rum from a duty-free bag. “I always thought the name was funny.”

“Did you? Me too.”

“As if this rum could spur a man on.”

“Ha ha.” She stood above me and poured some into my glass. I didn’t drink any. I was trying to stay aloof, let her do all the guessing, but I was dying to know how she had spent the week. She looked so happy.

When I put my drink down she went back to her luggage and said, “I want to show you something.” She bent over and unzipped her suitcase. I watched her. She took out a couple of legal-size envelopes. She came back toward me and put the envelopes on the arm of the couch. Then she stepped back, looked at me, turned around, faced me again, started undoing her dress button by button. She wasn’t wearing underwear. She asked me how she looked.

And she spun and spun and spun.

After about an hour I asked her what was in the envelopes. She had recovered some of her old remoteness, but my mention of the envelopes seemed to cheer her up.

“Have a look,” she said.

They were filled with photographs of her. She said the trip to Barbados was “a marketing exercise.”

“So you’re in marketing now?”

“No.”

She had become the face of Imovex. “They said they needed a face.”

So they flew her down to Barbados with some marketing managers, photographers, a film crew, and they watched her, filmed her, dressed her, choreographed her movements along the shore.

“And we drank punch all day. Planter’s punch. It’s like…”

“I know what it is. Was Tom Shaw there?”

“Yes.”

“He was. And was he able to tell you what exactly your presence on the beach had to do with open-source solutions?”

“Tom was nothing but kind all week.”

“Mmm.”

“It’s a big campaign. I wasn’t allowed to tell anyone before I left. Not for months.”

“So I’m the first potential customer.”

“I thought you would be excited.”

“What’s the campaign?”

“Flawless.”

“What?”

“That’s what it’s called. It was called Project Diamond during concept development. Now it’s called Flawless.”

“But you’re not in marketing?”

“Not really.”

“You’re a model now?”

“No. I’m the face of the company.”

“Tom’s idea?”

“Brainstorm.”

“Mmm.”

“We’re changing the whole look-feel. Anyway what’s with the questions? I had such a good trip, I feel so much better about myself, I come home, and you’re all suspicious and confrontational.”

“I feel like your diction has changed.”

“It’s common when someone is away for the other to look for change.”

“I see.”

“I learned a lot on holiday. You have time to think, get to know yourself.”

“I know.”

“Well, I didn’t. And it was so flattering to have these people filming me and taking my picture.”

She had a pleading look. Stroking my face, pleading for something.

I clicked on the Imovex website the following Monday, and there she was, my Jackie, standing on a perfect beach. The site had changed entirely: no more virtuous, macabre testimonials from Tom Shaw; just images of my Jackie, soothing colours, and links to what they called solutions.

“Imovex. Charles speaking.”

“Hi Charles.”

“Hello.”

“Charles, do you have any idea what your company is up to?”

“Pardon?”

“Hearing troubles, Charles?”

“Who is this?”

Jackie didn’t go to the office for a while. She was picked up by a car in the afternoons to take her to a studio. “You know, studio work,” she said.

“Touch-ups.”

“Mmm.”

I was stuck in traffic behind a bus one slushy winter’s day, thinking of Jackie, wondering what was missing between us, and there she was looking at me with gigantic eyes from the back of the bus. Imovex. Flawless Solutions. They had made her eyes the same colour.

Then we were walking together downtown one day, avoiding ice, eating bagels, and talking about my work, and we saw another bus pass with the ad on its side. Jackie looked demure when she saw it.

“It doesn’t look like you,” I said. I was going to say that she was more beautiful in person, but I said, “There’s a poppyseed between your teeth.”

And then the TV campaign began. Everyone is vulnerable to something. Close-up of Jackie’s face looking predatory, sexy—someone we would all be vulnerable to. But business should be vulnerable to nothing. Jackie walking in her bathing suit along the shore, feet just avoiding the water. Imovex. Flawless software solutions.

It’s a strange feeling to know someone so famous. When I saw her at home I would instinctively think, “Hey, I know you,” and then I would realize that I really did know her, knew too much of her, and the shuttle between excitement, pride, and resentment would exhaust me. She could have claims to superiority, fame, success, but we both knew that I was the superior one. The fact that she was turning into a modest, thoughtful person didn’t help my sense of confusion.

My introduction of her to my colleagues was long overdue, but I now hesitated further. They would only be more jealous, more competitive. I would be more protective, suspicious of her glances. We stopped going anywhere in public together.

“I noticed in the TV commercial that they covered up your tattoo.”

“Yeah.”

It had been a long time since either of us had mentioned the one great hurdle we had tentatively overcome. In the commercial, when she is walking along the shore, the camera is down and to the right of her. Her left shoulder, with its smudge, isn’t visible.

“I know what you’re getting at,” she said. “What?”

“You want to know what people said. On the beach. My colleagues. You can see them recoiling when they saw it.”

“Saw what?”

“You know what.”

“Your smudge?”

“Look at their faces. There. In your mind. Look at them all recoiling.”

“I haven’t met your colleagues.”

“And I haven’t met yours.”

I noticed in all the images of her—on the website, bus ads, television—her left shoulder was never in view.

“I bet you want to know,” she said, “whether it was my decision or theirs. Did they tell me to hide it, or did I hide it from them?”

“I just want you to be comfortable with it.”

“Do I look uncomfortable?”

“You look upset.”

“Did I look upset when I came back from holiday?”

No, she did not look upset.

“Either way,” she said, “it’s not a secret anymore. Right? Everyone knows I’ve got it.”

“No. Not everyone. Not the viewers. Not Tom Shaw’s customers. I’m just saying . . . ”

“That’s not what bothers you.”

“I’m just pointing it out. Raising the issue. Making sure you’re okay.”

“But that’s not the issue, right? That’s not the secret that’s really bothering you.”

“No?”

“You want to know whether they know who I am. Where did Jackie come from? You’re scared of them knowing.”

“No.”

“Why haven’t I met your colleagues?”

“They’re civil engineers. They would be jealous. You wouldn’t like them.”

“Have you told them about me?”

“Yes.”

“Who I really am?”

“I keep my private life separate from work.”

Jackie got drunk that night. It was a new ability she had picked up on holiday. She had started drinking at around 4 o’clock, and by the time she was cooking she was drunk enough to throw a knife at me. I was marvelling at how firmly she held an onion while she chopped it. “It’s amazing how much strength you still have in that arm,” I said, and she threw the knife, but the handle hit me first.

I never saw her in my house again. I got a letter in the mail.

“I’ve left,” she said. “I’ve learned about love and disease. And you taught me nothing.”

Like any parent, I know that she’ll come home. An embrace fraught with bad memories and past resentment is still an embrace, and necessary.

I saw a picture of her in the paper. “Software developer marries model.” A summer marriage. Such a smile. I’m certain that she hasn’t told him who she really is. He might think he knows her flaws, but he doesn’t know she’s mine.

Tom Shaw is bold enough to leave his email address on the Imovex website. I send him emails every day.

Check out this cool site.

Grow your p.eni$$

Nice to see you yesterday.

Most often the subject is Jackie, and I cram the messages full of viruses.

One day I’ll get through.