“I first came across Jane’s work in the early nineties. She has told me that the title of her installation, African Adventure, stems from a travel agency in South Africa that goes by the same name. Since the end of apartheid, South Africa has become a curiosity. Everyone started putting together South African art exhibitions. It became the new fashion and it reminded me of what happened with eastern European artists after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Before that time, South Africa was not the place to be.

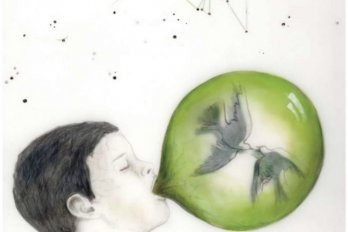

“The characters in Jane’s installation, which are half human and half animal, seem to be coming from a nightmare or post-nuclear war. There is a kind of mutiny and you don’t really know who’s who. There is a human figure with tools attached to him. The tools are farm tools, to work the soil, which is where life comes from. The red earth reminds me of a burned-out country, something very dry, a land where nothing can grow. I might suggest that those well-dressed characters in the work represent Europe looking at Africa. They’ve come to look at this African adventure.

“When Jane started making art during the 1980s, her country was still very closed off—it wasn’t part of any kind of mainstream. Right after Nelson Mandela was released, I made my first trip there. After apartheid, it seemed no one in South Africa knew exactly who they were. What was most interesting for me was to see that a white person didn’t know how to behave anymore; they didn’t know how to behave toward a black person and vice versa. The boundaries were no longer clear. I don’t mean to generalize; of course there were individuals that this would not apply to, but the big picture changed, and Jane’s characters are the products of those troubled times.

“Jane doesn’t often speak about her work and I think that when an artist speaks too eloquently, I tend to be suspicious. Maybe I’m still naive but for me there’s a kind of magic in a work of art. It is something an artist produces, but they don’t know exactly why. If you are not told what you are looking at it allows for interpretation. We might be right or we might be wrong about what it means, and the artist might discover things they had not suspected earlier. Universality starts from a very specific, localized point. It’s richest when it’s readable in any part of the world without having the stereotypes of localization. Jane does this naturally.”