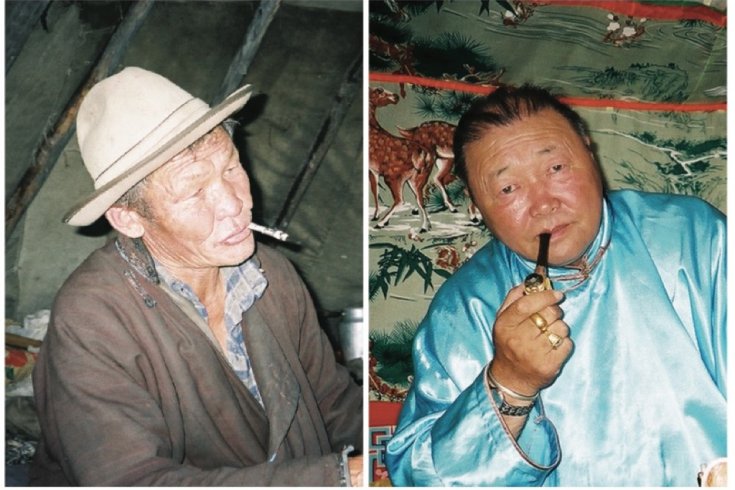

hovsgol province/ulaan baatar—On a sunny afternoon, a man sits on the floor of his teepee (or ortz) in the mountains of northern Mongolia, drinking salty tea with reindeer milk and smoking cigarettes rolled in strips of newspaper. He is Ghosta, fifty-nine, a handsome man with high cheekbones and a broad, rugged face. Yet there is sadness in his eyes.

“My life is hard,” he says, more than once. He might be referring to his life as a nomadic reindeer herder, but no. He is talking about being a shaman.

“I have a responsibility for people in the community,” he says. “People who are struggling with sickness come for help and I cannot refuse.”

Ghosta is one of about 200 members of Mongolia’s Dukha minority who eke out an existence as reindeer herders in the alpine taiga along Mongolia’s border with Siberia. They move with the seasons, subsisting mainly on reindeer cheese and bread.

There are perhaps half a dozen shamans among the herders. They are the priests and healers of an ancient religion, the bridge between this world and that of the spirits. Here in the countryside, they keep the old ways, performing rituals only at night, in strict accordance with the seasons and the phases of the moon. They are wary of outsiders, and Ghosta talks only reluctantly.

He found his calling at the age of twenty-five, he says, at a time when he was “sick and becoming unconscious.” Shamanism is a family tradition, and the spiritual congress often begins when the future shaman confronts a life-threatening illness. Ghosta describes the day when he awoke from a mysterious sleep to find his father performing a ritual. “My father told me to put on his costume. I wore it for a while and took it off.” Soon after, he became a shaman.

“That was during socialism times,” he says. “Everything had to be done secretly.”

Under the Communists who ruled Mongolia for most of the twentieth century, shamanism, like all forms of religious expression, was banned. Despite the controls, life under the Communists was easier for the reindeer herders. Their animals were collectivized—made official state property—and every herder received a monthly stipend.

A democratic revolution in the 1990s returned the herders to the laissez-faire existence of their forebears. When they ran short of cash, they were forced to sell or slaughter many of their animals. The herd has dwindled to some 650 today, down from more than 2,000 a generation ago.

Even by local standards, Ghosta’s tent is stark. The canvas is old. Worn blankets and skins are rolled and stacked around the perimeter. His shaman drum and costume are hidden behind a green cotton curtain, opposite the door. Ghosta has had bad luck in his life: a divorce, the death of a son. He says the trouble began when he helped someone who later refused to make an offering to the spirits. “That was bad for me, as the mediator in between. That’s why my son died.”

“This is not play,” he says. “People in Ulaan Baatar treat it like theatre.”

Three days’ drive to the southeast, the Mongolian capital thrums with new energy. Just beyond the parliament building, a statue of Lenin stares out over a boulevard jammed with old Russian jeeps and new Japanese suvs. Capitalism has taken hold here.

Alongside a busy road sits a round white tent—a Mongolian ger, or yurt. Above the door, a blue-and-white sign announces “House of Mongolian Shamanistic Ritual” and, in smaller lettering, “Byambadorj, the shaman.”

Byambadorj, the urban shaman, arrives mid-morning to work. He’s a large man, verging on corpulent; he wears his thinning hair in a ponytail. Under Communism, Byambadorj worked as a driver, but now someone else chauffeurs him around town.

Six customers wait on a bench outside the tent; most are here for the first time. Byambadorj enters without even glancing at them. One man, Dovchin, is a meat-seller who looks to be in his thirties. He says that booze is ruining his life. He has tried to quit. Counselling, pills—nothing worked.

Inside the tent, Byambadorj seats him on a low chair. The shaman shakes a rattle and shouts to the spirits, “Shosh! Shosh!” He paces the tent, slapping Dovchin with the flat of a sword, then, amazingly, spritzing him with a spray bottle of vodka, until Dovchin drips and the air fills with the smell.

After ten minutes, Byambadorj stops to regard his patient, “I can see light in your face,” he says softly. “The Eternal Sky is going to pull you up.” Dovchin pays for his session in cash, the equivalent of half a week’s wages for most Mongolians. For the moment, he considers it money well spent.

Byambadorj says business is good. The demand for shamans is increasing. He rummages around his desk for a handful of business cards and a photocopy that lists his credentials. “Nowadays, shamans are more interactive with the world, more modern,” he says.

Ghosta, with his sixty head of reindeer and simple ortz, counts four generations of shamans in his lineage. Byambadorj claims nine. “There is not one God, but many,” Ghosta says. “They have chosen me and taught me to be a shaman.” To Byambadorj, “There are different spirits with different purposes. There is no manual to follow; it is up to his own free will.”