Why Bush Will Win

As Canadians lick their wounds over our national election result – a minority that carries with it the likelihood of another round soon – we should be thankful for our limited campaigns compared to the endless electioneering in the United States. The Iowa caucuses and the “Dean scream” – replayed endlessly by cnn – may seem long ago, but the mad dash for the White House has never stopped.

With Canada’s relationship to the U.S. now high on our list of concerns, this time around Canadians are more than passive spectators to the blood sport that is the U.S. presidential election. Other than sheer duration, perhaps the starkest difference between the U.S. and Canadian electoral contests lies in the nakedness of the American candidates’ appeals to values. Republicans, especially, trade freely in the rhetoric of God, country, and family. Stephen Harper did his best to keep this sort of language locked in the barn. When his would-be backbenchers piped up about these issues, their remarks were usually met with a national gasp and a sharp elbow from campaign organizers.

In the U.S., “Campaign 2004” got a jolt when the Democratic contender, Massachussetts Senator and Vietnam War veteran John Kerry, announced on July 6 that North Carolina Senator John Edwards would be his running mate. This was yet another blow in what was not an easy week for President George W. Bush. The Senate Intelligence Committee criticized what one commentator called “artificial intelligence” from the cia on Iraq’s supposed stockpile of weapons of mass destruction and on Saddam Hussein’s link to Al Qaeda; the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that “enemy combatants” incarcerated at Guantanamo Bay deserve due process; an increasingly non-compliant press suggested that abuses in Afghanistan prisons matched those at Abu Ghraib; and, as these developments played out, Americans were being asked to consider whose account of the state of the world was more honest: Bush’s or the documentary filmmaker Michael Moore’s as enunciated in Fahrenheit 9/11.

Hanging in the balance were suggestions that it didn’t matter one whit what the cia said about the Iraqi threat – the U.S. Army, Navy, Marines, and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld’s smart bombs were going in anyway. The last news Bush needed was that, with Edwards on the Democratic ticket, he couldn’t even take the South for granted in November. As the swaggering LBJ buoyed the patrician Kennedy, so, too, could Edwards help nudge the Senator from Massachusetts into the Oval Office.

But vice-presidential candidates, however they might flavour a campaign, don’t ultimately make or break their running mates. (A stark case in point was 1988, when Lloyd Bentson outshone the endlessly befuddled Dan Quayle, not least when he assured Quayle in debate that he was “no Jack Kennedy,” a brilliant improvisation that echoes still.) Bush’s response to the announcement of the Kerry/Edwards ticket was telling: Homeland Security Director Tom Ridge was put before the nation to announce that another Al Qaeda attack on American soil was planned, and the Bush team argued that Kerry didn’t have the values to protect the American people. Terror and values were thus established as central Republican election themes. Informing both is the Bush mantra: “You are either with us or against us” – with us in Iraq, with us on the Patriot Act, with us on the “defense of marriage,” or against us on all three.

It may be that this tack represents a desperate grasp from a president and a party unable to run on their economic and foreign-policy records. But even so, liberal commentators are wrong to dismiss it. This is a race not for the mind but for the soul of America, and there may well be enough true believers to propel Bush to a second term, whatever the shortcomings of his first.

To American progressives and many Canadians, the re-election of this president seems not only incredible, but alarming. The prospect of a Bush victory in November, however, is in fact quite plausible. There are two main reasons for this. One has to do with values – the values of Republicans and the values the Bush administration projects – and the other has to do with voting patterns in the United States. Only about half the population votes in the United States; so it matters very much who shows up at the polls. Half of America elects the president; which half?

Let’s begin with values. If the election were to be decided solely on the values projected by the candidates (as opposed to more concrete policy issues), Bush would win by a healthy margin. Most Americans are conservative on social issues – they favour capital punishment, oppose gay marriage, and trust religious candidates more than secular ones (avowed atheists and agnostics are virtually unelectable in America). President Bush appeals fairly well to the values of Americans who consider themselves moderate, and he has self-identified Republicans sewn up.

Republicans’ core values are religiosity, propriety, obedience to authority, duty, national pride, and belief in the traditional family. Here Mr. Bush is masterfully positioned. He is a born-again Christian and a reformed alcoholic. He supports faith-based initiatives and home schooling, presumably to protect the offspring of his evangelical brethren from the secular liberalism of public schools. He pledged to restore “honour and dignity” to the White House after the Lewinsky scandal, and to that end has instigated a suit-and-tie dress code in the West Wing. (Khaki-clad policy nerds, so welcome in the Clinton White House, need not apply.) Bush has relied heavily on the gravitas that deferential Americans automatically assign to the occupant of the Oval Office, almost regardless of that individual’s words or actions. Playing up his solemn duty as commander-in-chief of the world’s most formidable military, Bush can count on half the electorate to revere his office and defer to its occupant as a matter of patriotic duty.

Duty is an important element of the Bush brand: this president stresses that he doesn’t want to act unilaterally to fight a war against evil; he must. He reminds Americans that they, too, must make the necessary sacrifices if darkness visible is to be vanquished for all time. Dissent in Bush’s America is unpatriotic. America is the greatest nation on earth; as such, it has special rights, grave responsibilities, and a manifest destiny to make the world safe for democracy and freedom. Against his liberal critics, Bush is positioning America’s interests as world interests. Furthermore, his proposed constitutional reform to ban gay marriage is part of a larger warning that America is under siege internally, that liberal values can be as corrosive to the American dream as terrorist threats. (Pennsylvania Senator Rick Santorum has called the fight against same-sex marriage “the ultimate homeland security” issue.)

Some of the credit for Bush’s success in appealing to Republican values belongs to him and his advisers. To some extent, though, the Bush camp is merely lucky: Republicans are much more coherent, in both their demographics and their values, than are Democrats. This coherence makes them easier to please and easier to mobilize. The Republican party derives much of its support from the rich and from religious conservatives, and it is more uniformly white than its rival party. Many Republicans fit all three categories: affluent, white, religious.

The values of these Republicans are not difficult to intuit. They see themselves as rule-followers and honest brokers. Their affluence is their just reward for hard work, ingenuity, and personal virtue. Their enemies abroad – terrorists – play by no rules and believe in the wrong God. Their enemies at home – liberals – are godless and seek to undermine America’s greatest strengths: individualism, religiosity, moral certitude. They believe in their president almost unconditionally and distrust those who do not.

The Democrats, by contrast, are faced with the challenge of trying to attract the votes of several more widely divergent groups. The Democratic Party relies on support from the black and Hispanic communities, organized labour, and liberal progressives; in partisan terms, these groups are the remnants of the old Democrat coalition from FDR’s New Deal and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, but to call them a coalition today is to overstate their unity. On values, Democrats are much more prone to fundamental divergence than the main Republican sub-groups. The Democratic sub-groups would have a harder time sitting down for dinner together than the Republicans. Whereas the Republicans could agree on meat and potatoes, Democrat fare would range from fast food to fusion – the trouble would start before anyone had even ventured a political opinion.

To a great extent, liberal progressives are defined by their rejection of core Republican values (e.g., religious and patriarchal authority, the belief that the only legitimate definition of family is the traditional nuclear one, and strict meritocracy). To them, the rich have a moral obligation to help the poor and protect the environment. They are wary of the hail-to-the-chief hierarchy embraced by Republicans (and fanned vigorously by the Bush administration). Liberal progressives support heterarchy, a relatively flat model of human organization in which leadership is fluid – Dad is the boss on one matter, Mom on another, this senior executive might lead one project and that junior manager another, with everyone compromising and debating points of view.

Values surveys find that Hispanic Democrats espouse a stronger belief in the family than do liberal progressives, and report greater acceptance of patriarchal authority. They basically trust the free market, have considerable faith in big business and advertising, and believe that people generally get what they deserve in life. In many cases, these citizens have come from places – Puerto Rico, Cuba, Mexico – devoid of the opportunities promised by the American Dream and, unlike much of the African-American component of the Democrat coalition, have yet to conclude that the dream is a myth for all but an exceptional few.

Black Democrats and Hispanic Democrats share more common ground with each other than with liberal progressives, but values research reveals significant differences between them. Black Democrats, like Hispanic Democrats, are reasonably deferential to patriarchal authority, and exhibit relatively high levels of faith in business, media, and advertising. But black Democrats diverge from Hispanic Democrats in their belief in activist government, and in their conviction that the rich have an obligation to help the poor. Black Democrats are also set apart by their attitudes toward status and consumption. Whereas black Democrats register an attraction to conspicuous consumption, liberal progressives are more likely to spend money on experiential hedonism.

Democrats who live in households that include at least one union member display another distinct set of values to which John Kerry must cater. Like liberal progressives, union Democrats are flexible with respect to the definition of family and don’t embrace the religious and authoritarian values of Republicans. The values that stand out among union Democrats that do not stand out among the other three sub-groups relate to personal fiscal restraint: union Democrats believe in saving on principle and reject impulse consumption.

Clearly, a relatively scattered picture of the Democratic Party emerges when the values of its most important component groups are considered. Self-identified Democrats eschew the ostentatious religiosity and patriarchal authoritarianism of Republicans, and are more open-minded about family structure, but that’s where the consensus ends. Republicans, by contrast, have a strong web of shared values and myths that Bush can leverage with ease and effectiveness. Republicans do sometimes disagree, as when religious conservatives and states’ rights advocates clashed over the constitutional amendment on same-sex marriage. But in the wake of particular policy disputes, their shared values – God, country, family – make it easier for them than for Democrats to reunite under some symbolically resonant banner. In a media-saturated age when sound bites and rapid-fire images are the main currency of a campaign, the fact that Republicans can more easily invoke symbols and core cultural values that will be meaningful and appealing to their supporters is an enormous advantage. Thus, it is safe to say that if the 2004 election were solely about values, the Republicans would have it.

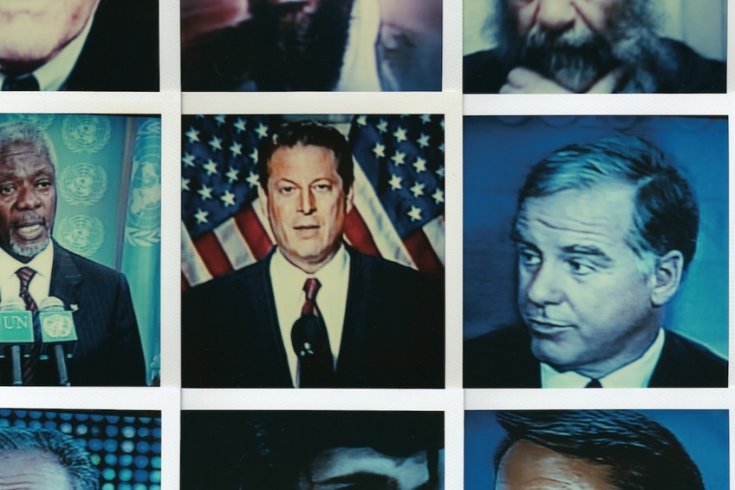

Values play another role that may work to get George W. re-elected: influencing who turns out to vote. In the 2000 election, 51.2 percent of the voting-age population turned out to vote. Even setting aside the debate over the legitimacy of the Bush victory, it is uncontested that Al Gore received the larger proportion of the popular vote. This means that less than a quarter of U.S. voters chose the man who became president.

Obviously, getting the vote out is a crucial task for any candidate. Campaign organizers salivate over swing voters, but the number of non-voters is vastly greater. In a race as close as 2000 was, or as 2004 is, a candidate who could mobilize some portion of the electorate that would otherwise not vote (turnout among the American poor is particularly dismal) would have a huge advantage. But that scenario is unlikely; voter disengagement is a difficult, if not impossible, tide to turn.

So who does turn up to vote in presidential elections? The Americans who are most likely to vote are people who believe strongly in the traditional family, propriety, everyday ethics, and personal duty. They report high levels of religiosity and national pride, believe in the promise of the American Dream, and in civic engagement. If this list sounds familiar, it is because those are precisely the values of Republican supporters.

Republicans are more likely to feel a duty to vote than are Democrats. There are many reasons to vote, including ideological fervour and perceived self-interest, but these don’t position voting as in itself an important act.

Suppose you don’t think either candidate advances your own interests. If you lean Republican, you may turn out to vote anyway, simply because the exercise of your franchise is a non-negotiable responsibility. If you lean Democrat, you are less likely to show up at the polls to support a candidate you don’t find compelling. (The third option, Ralph Nader, will likely be less of a factor in 2004, his support petering out much as Ross Perot’s did in 1996 despite a fairly solid showing in 1992.)

For the most part, Americans who vote have won or feel themselves to be winning a slice of the American pie. Those who have not scored big believe, as American life demands, that they may yet win – but if they do, it will be through hard work or luck, not by a change in public policy. Such changes are things that Canadians, by contrast, depend on – their beloved public health care, social programs, and transfers all come from the public trough, a trough Americans don’t expect will ever help them much. Neither the ideal of the good life nor that of the common good motivates American voters; rather, they arrive at the polls out of what economists call loss aversion: the desire to safeguard what they already have. Prior to 9/11, Americans feared mainly the losses they might suffer to forces within America – economic difficulty, a criminal underclass, alienated children, illness in the absence of adequate insurance. Since 9/11, the fear of attack from those who wish harm on America has added to domestic fears. And as fear begets violence and violence begets fear both at home and abroad, the stark good-versus-evil world of George W. Bush becomes easier to peddle.

Predicting election results is a game for gamblers and fools, like asking Albert Einstein who will win this year’s World Series. This lesson was recently driven home in Canada, where published polls did a poor job in predicting the outcome of the federal election. In the U.S., holding constant the economy and barring, heaven forbid, a terrorist attack, or assassination attempt, or any number of more trivial surprises, I believe Bush has the edge based on the values he represents. Even in the event of a Kerry victory, the fear and fundamentalism that have brought us this far will not disappear; the Bush administration has articulated and embodied one set of American values that shows no signs of dissipating any time soon.

—Michael Adams

Why Kerry Will Win

In February, 1996, when the right-wing firebrand Pat Buchanan looked improbably close to winning that summer’s Republican presidential nomination, I paid a call on Barry Goldwater at his hilltop home in Scottsdale, Arizona. It seemed a good moment to interview one of the icons of American conservatism, the man who had given the Republican Party a populist ideology broad enough for politicians as different as Ronald Reagan and Buchanan to consider themselves his heirs. At eighty-seven, Goldwater was just months away from the stroke that would hasten his death two years later. He rarely gave interviews any more, and I was, frankly, astonished that he had agreed to see a journalist from “socialist” Canada. I was even more astonished to discover that he was a graceful, articulate host – nothing like the demagogue the media had delighted in skewering for years. Perhaps, I thought, age had mellowed him. Moving slowly, he led me upstairs to show off his latest acquisition – a powerful telescope that allowed him to spend hours staring at the night sky (“my newest hobby”) and he basked in my admiration of the museum-quality collection of Native American kachina dolls crowding his den. But when we finally sat down to talk, he was the lion in winter. Casting mellowness aside, he went after the man who laid claim to his legacy: Buchanan himself.

At the time, Buchanan was on a roll. He was still relishing the fright he had sparked with his “culture wars” speech at the gop convention in Houston in 1992. That year’s election, he announced famously, was about a “cultural war as critical to the kind of nation we will one day be as was the Cold War itself.” Buchanan’s world was black and white: on one side were the gay-rights-promoting, America-hating liberals; on the other were the God-fearing, patriotic Americans. His August 17, 1992, call to arms arguably cost the first President George Bush’s re-election to Bill Clinton but, undaunted, Buchanan was back at it again in 1996, railing once again about the perils of immigration and free trade. Goldwater, whose 1964 presidential campaign Buchanan once gushed was “like a first love” for lonely American conservatives like himself, was appalled. “It’s very difficult to sit and watch [him],” he grumbled. “He wants to take the concept of conservatism into avenues that it’s never been.” That, of course, was what they used to say about Goldwater as well, but the old warhorse refused to be pulled into further discussion. He just wanted it made clear that he believed Buchanan was steering his party towards catastrophe. His purpose in seeing me became obvious: this was a rehearsal for going public. Within months, I was reading Goldwater interviews in U.S. newspapers containing virtually identical thoughts. Conservatives tried to pretend the Old Man had simply lost it. “I won’t say betrayal,” Leo Mahoney, a staunch Arizona right winger who had been one of Goldwater’s closest political allies, told me after the interview. “But a lot of us believe he has changed too much for our liking.”

Maybe he had, but the Republicans badly need a dose of Goldwater straight talk today. The conservatives who have occupied the White House for the past four years are in precisely the kind of trouble Goldwater could have predicted for them. Despite having led the United States through one of the most trying times in its history, they now face a political defeat that will be entirely of their own making.

Goldwater had long ago recognized the fatal weakness in the U.S. conservative movement and had been trying to correct it ever since: don’t get so far out in front of American mainstream thought, he would undoubtedly have told them today, that it’s impossible to find your way back. (It was, arguably, the reason he lost by a landslide in 1964 to President Lyndon Johnson.) George Bush’s Republicans, battered by foreign and domestic misfortune, and blinded by conviction, are not likely to take the point. To the end of his life, Goldwater considered himself a faithful conservative. But he was also a political realist. And a coolly Goldwaterite look at America’s political landscape leads to only one conclusion: John Kerry will beat George Bush on November 2.

I can think of four general reasons.

The Democrats Control The Agenda This Time: Republicans say they are delighted by the 2004 Democratic presidential ticket. They’ve lost no time in pointing out that John Kerry had the most “liberal” voting record in the U.S. Senate in 2003 (John Edwards, his running mate, had the fourth), as rated by conservative Republicans’ bible, The National Journal. Nicolle Devenish, the communications director of the Bush campaign, calls Kerry and Edwards too “far out of the mainstream” on the “kitchen table issues that we think people are going to vote on.” No prizes for guessing that will be a template of the Republican drive this year. After all, it’s worked before. But will it work this time?

I don’t think so. It’s true that even though American “liberalism” has travelled far from the era of Franklin D. Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson, it remains vulnerable in normal times to Republican accusations that it stands too far to the “left” of the American mainstream (whatever that really is). All the same, these aren’t normal times. And the suicidal tendencies Goldwater detected eight years ago in the Buchanan campaign have solidified today. Under the pressure of hardliners, the Bush administration (and Bush himself) have pushed so far to the right that there’s room in the centre. Enough room, at least, for the Democrats to present themselves as a reasonable alternative to Americans saddled with an increasingly unpopular and costly foreign war, an economy that has left the middle class struggling to make ends meet, and with the unsettling feeling of being alone, vulnerable, and unloved in a world that they happen to dominate.

The broad popularity of Michael Moore’s anti-war documentary, Fahrenheit 9/11, illustrates why the Democrats now have an agenda with traction. The Moore film filled theatres across the country when it came out, and not just in the urban strongholds of the intelligentsia. Even theatres near army posts, such as Fort Bragg in North Carolina, reported sell-out showings. The spectacular show of national unity behind the Bush administration’s “war on terrorism,” evoked by the September 11 attacks, has dissipated. Despite the political truism that a war president always has the edge on public loyalty in the U.S., the ideologically driven foreign policy of the Bush administration (Iraq providing just one example) has become a partisan issue that increasingly puts the Democrats closer to the centre of American politics.

gop strategists believe they still have the advantage, thanks to the continuing strength of the coalition exploited by Reagan in the 1980s between blue-collar Democrats in the Midwest and Sunbelt voters in the U.S. South and Southwest. But here again, they’ve lost control of the agenda that kept that coalition vital. Over the past four years, nearly two million jobs have been lost – many of them among the very blue-collar and white-collar voters who once swung to the Republican side. Large swaths of middle-class America are unmoved by signs that the economy is picking up: they are too worried about making ends meet. A Time poll in July found that 51 percent of eligible voters believed that the rich have gotten all the benefits of the Bush tax cuts, while the middle class has been left to pick up the crumbs. And then there’s the question of security, which again was once the Republicans’ strong suit. Three years after the September 11 attacks, the polls show that Americans continue to feel vulnerable and insecure – a feeling that has not been mollified by the administration’s persistent and vague warnings of coming terrorist attacks.

In 2000, Bush struck a chord with Americans when he argued that the fortunate coincidence of post-Cold-War peace and a then-booming economy provided an opportunity for the country to rediscover its moral core. Now, ironically, if the warnings launched to such good effect in the 1990s by right wingers such as Buchanan and populists such as Ross Perot about losing jobs to foreigners and national identity to a globalized world retain any appeal at all, they are being made most effectively by Democrats. Both Edwards and Kerry, for instance, have promised to protect American jobs from outsourcing. There is, of course, always the possibility that Bush will try to recapture that resentment and turn it to his own advantage, starting with the party’s national convention held symbolically in New York, ground zero of the war on terrorism. But the effective lock down of the city to ward off potential terrorist attacks conveyed a contradictory message from a president who hopes to argue he has made the country safer. In any case, the Republicans lose out on another of their key selling points: the strengthening of American “values.”

Democratic Populism Trumps Republican Values: Bush and Kerry have been neck and neck in the polls for months. With the numbers so close, campaigners on both sides are fighting for a narrow, geographically specific section of the middle class in key states that have been most impacted by job losses and the march of their young men and women to war. This segment of the U.S. population is marked by resentments and insecurities not seen since the pre-Reagan era. It’s not a fertile market for the Republicans’ value-based campaigning. Particularly, the appeal by Bush and allies to hot-button issues such as same-sex marriage (which seems to have replaced abortion as their favourite bête noire) threatens to alienate moderates and swing voters who are more pragmatically inclined. The late President Richard Nixon, who prided himself on his pragmatic approach to politics, won in 1968 against Democrats weakened by divisive ideological fights, thanks to his appeal to the “Silent Majority.” If that majority still exists, it’s likely to be partial to the Democrats.

Nothing captures the change more than the Democrats’ vice-presidential choice, John Edwards, who has built his short political career by speaking out credibly for “middle-class working Americans” in a way that the Democrats haven’t been able to do for a decade. Edwards even comes with a ready-made rags-to-riches story. Although his previous career as a trial lawyer earned him an estimated $44 million (U.S.), he’s the son of a poor mill worker. And his empathy skills rival Bill Clinton’s. The Edwards speech on the “Two Americas” is a classic: with lines such as “one America that does the work, an¬other that reaps the reward” or, more pointedly, comparing “a middle-class America whose needs Washington has long forgotten” to “another America whose every wish is Washington’s command,” Edwards captures the sunny but hard-edged populism that Reagan managed to perfection. Conservative commentators such as Fred Barnes, editor of The Weekly Standard, say this throwback populism won’t work with independent and swing voters who “don’t see America as a nation in which an economic elite oppresses everyone else.” Maybe, but it’s no coincidence that during his campaign for the Democratic nomination, Edwards promised “the most vigorous enforcement of the anti-trust laws that we’ve seen since Teddy Roosevelt.” Roosevelt, a Republican president, once memorably warned against putting power “in the hands of those who sought not to do justice to all citizens, rich and poor alike, but to stand for one special class, or for its interests, as opposed to the interests of others.” Take that, Enron.

The Conservatives Are Eating Their Young: One of the most interesting political books to come out this year is The Right Nation: Why America is Different, written by two journalists from The Economist, John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge. The book argues that the Conservative movement in the U.S. has been one of the most successful political stories of modern Western democracy, having moved slowly and stealthily from its Goldwater beginning to the triumph of Ronald Reagan. The secret of its success, they say, is the right’s ability to channel its intellectual arguments through institutions that now dominate American culture. There are now hundreds of Conservative think-tanks, they point out – a kind of “Right Bank” of conservative thought created from a fractious and unlikely mix of Jewish intellectuals, Christian evangelists, anti-tax crusaders, and gun-rights advocates. The Left, by comparison, is worn out by decades of infighting and has few new ideas, they add. It’s a powerful argument, and at first glance it seems accurate. This “Right Nation” is the America that Canadians and the rest of the world see: strident, self-assured, comfortable in its sense of historical inevitability.

But that coalition has become increasingly crunchy. And pieces of it are starting to fall off. In the early years, the inner circles of the Bush government had the rigorous discipline of Marxist cells – and the same fervent sense of mission. At the Executive Office Building next to the White House, announcements of prayer breakfasts peppered the bulletin boards, and earnest young men in obligatory suits and ties strode the corridors, in pointed contrast to the laid-back sartorial and intellectual restlessness of the Clinton era. Now some of the most vicious gossip about the administration is being spread by former Bushites in books and leaks. The “neo-conservatives” who provided the intellectual arguments for the war, and for the aggressive, unilateralist foreign policy that underpins it, are colliding with traditional Republicans who have always felt uncomfortable with foreign entanglements. Meanwhile, the evangelicals simmer over what they believe is lukewarm support for their own favourite policies. And moderate Republicans are privately enraged by the air of incompetence and disarray hanging over Washington. The Bush troops have even lost Nancy Reagan’s support over their objection to stem-cell research.

The Ground War Favours The Democrats: This time, it’s all about the ground war, stupid. Although the 2000 election was famously (and controversially) close, it’s easy to forget that Bush was several points ahead of Al Gore in national polls during the final weeks of the campaign. Only a last-minute push by re-energized campaign workers among core constituents such as African-Americans pulled states such as Pennsylvania into the Democratic column. The same razor-thin battles are likely this time around – and Democrats are now better prepared on the ground than they were in 2000. Armies of workers inherited from the volatile Dean campaign, activists from unions, anti-war organizations, women’s groups, and ethnic constituencies have so far avoided the ideological squabbling of earlier campaigns to demonstrate a grassroots unity that was notoriously lacking in the Bush-Gore contest. One result: the Democrats amassed a bulging war chest early enough to challenge the Republicans’ spending. Another helpful factor is the number of Americans who say they will vote this time. A Pew Research Centre survey in July found that 63 percent said this year’s election result “really matters,” almost 20 percent higher than in June, 2000, when only 45 percent felt that way. In a re-election campaign, that’s another sign of a galvanizing opposition. Just as telling is the difficulty Ralph Nader, America’s consumer safety crusader, has had in gaining support and attention for his repeat run for the White House – so much so that concerned Republicans have been quietly helping him out. They can read the polls as well as anyone else.

Polls can be misleading, as anyone who followed the Canadian election knows. Nevertheless, based on those four general propositions, Kerry is my bet to win. Some thoughtful right-leaning Republicans seem to agree. Writing in The Wall Street Journal on July 14, Hoover Institute Fellow Morris Fiorina complained that Republican operatives “have bet the Bush presidency on a high-risk gamble.” Their strategies so far, he observed, “suggest that they are attempting to win in 2004 by getting out the votes of a few million Republican-leaning evangelicals who did not vote in 2000, rather than by attracting some modest proportion of 95 million other non-voting Americans, most of them moderates, not to mention moderate Democratic voters who could have been persuaded to back a genuinely compassionate conservative.” Barry Goldwater couldn’t have said it better.

But if not Bush, what would such a Genuinely Compassionate Conservative look like? I asked Goldwater in 1996 who he thought could lead the Republican Party to the kind of victory that would ensure the New Conservatives’ staying power in American politics. He didn’t hesitate. “Colin Powell,” he said.

—Stephen Handelman