If you look at Bolivia’s capital city of La Paz in a certain light – and light is the sovereign element here, glinting off the tin roofs of the valley and turning the windows of the high-rises into panes of gold – it offers you a near-perfect map of the tenses. At the centre of town is a model of the colonial past: the classic Spanish Plaza Murillo, with a legislative palace on one side, a presidential palace and adjoining cathedral on another, and, on a third, the Gran Hotel París, a fading relic of yesterday’s glories that beams out the word “París” acrossthe city skyline after dark. In the middle of the plaza is a statue. “Glory,” “Union,” “Peace,” and “Force” cry from its four sides, and, around it, cavorting nymphs stand in for the classical arts.

Just a few minutes’ walk from that official home to imported power, still used by Bolivia’s leaders, is what appears to be the present tense: the flower-filled elegance of the Prado, the closest thing to the Champs Elysées that La Paz has to offer. Aymara women are perched in huts in every corner of free space, peddling pyramids of Pringles cans, pirated videos of Ricky Martin, and enough copies of Peter Drucker’s works on management wizardry to occupy the citizenry for a century. But all of them are dwarfed by the signs of official progress all around. Outside an elegant McDonald’s, an armed guard protects the high-tech burger joint, which advertises prices higher than those of the Parisian café next door. Across the street gleam Internet cafés and kids on cell phones. And at the end of the spacious boulevard, a long straggly line of labourers is gathered in a silent queue around the base of a glass skyscraper, at the top of which flies a banner that says, “The Future of Bolivia.”

In reality, the future lies not here but a few minutes’ drive through Sopocachi (the embassy area, full of”Latin jazz” clubs and Tex-Mex hang-outs), down in the Zona Sur valley to the south. The Burger King there is as large as a Mercedes showroom, and the Hypermarket on the corner seems to subvert everything that swarms and sprawls across the Indian market above it. The names of the straight streets of the Zona Sur are the traditional ones – Calacoto and Cotacota, Achumani and Chasquipampa – and yet the whole clean suburb has been made to look like what the affluent, at least, might associate with the future. The karaoke parlour here is called “America,” the shopping mall “San Diego.” As I sat one night in a pizza place, its prices higher than those in Miami, a high-school girl at the next table, soignée as Catherine Zeta-Jones, closed her eyes and sang along, transported, to “Hotel California” on the soundtrack. Hotel California might as well have been down the street.

Yet the saving grace of Bolivia, and what makes it irresistible for anyone eager to escape the simplicities of preconceptions, is that it stands all such theories on their heads. The real heart of town, just blocks away from the Spanish plaza, is the Indian marketplace, the living past, where women in bowler hats offer llama-fetus charms and tribal aphrodisiacs along with copies of Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man. The costume they wear is itself something of an illusion: the plaits, many-coloured ponchos, and bowler hats that we tourists take to be such a picturesque aspect of the native culture are, in fact, the legacy of an eighteenth-century Spanish king. Where, in cities such as Lima, you may occasionally note a splash of indigenous culture in the midst of what is otherwise a Spanish city, in La Paz it can be startling to see occasional pieces of Spain in what is, for all intents and purposes, a South American province of the fourteenth century. The future of Bolivia, you cannot help but feel, lies in its past.

The traveller, if he comes from a place of comfort, travels in part to be stood on his head – to lose track of tenses, or at least to journey back to essentials, free of the details of home. “Teach me,” as the Trappist monk Thomas Merton wrote in his journal, “to go to a country without names and words and terms.” Yet if he is to travel far enough away from the places he knows, the traveller is also obliged to see everything in two ways, to speak in two languages at once. On the one hand, he’s a newcomer who’s walking down the street, unable to read the signs, with the map in his hand held upside down; on the other, he has travelled to look at himself (and his world) through the eyes of the local, for whom the newcomer is a source of strangeness and comedy, descended from another planet.

In Bolivia, this doubleness confounds you at every turn, in the most indigenous country in South America, where people speak languages that have had, until recently, no written form. And so all the guidebook facts, the World Bank figures, that you’ve brought with you have to be thrown out. You’ve read, perhaps, in The New York Times, that Bolivia suffers from the worst rural poverty in the world; ninety-seven percent of the people in the countryside, according to the UN, live below the poverty level. Yet as you walk along the Prado, fathers bouncing their children on their shoulders while Goofy and Mickey share a sleigh with three rival Santas, poverty is not the first word that comes to mind. You’ve seen, no doubt, in the Guinness Book of World Records, that Bolivia enjoys the unhappy distinction of having suffered more changes in government than any other country (188 in 157 years) – the most recent on October 17, 2003, when President Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada had to flee the presidential palace by helicopter, the La Paz airport having been shut down by demonstrators.

Yet as you stroll among the country’s people, policemen walking hand in hand with their wives, girls drifting arm in arm, sidewalk artists setting up Fidel Castro next to Harry Potter, the word you hear most often is tranquilo. And you’ve read, if you’ve done your homework, about a country filtered for us through the accounts of Hunter S. Thompson and Che Guevara and Klaus Barbie, the former Nazi who lived in comfort in La Paz for decades; yet when you arrive in La Paz, its light so resplendent that you feel as though you’re on the edge of heaven, its lovers pressed against one another in the shadows of the colonial quarter after dark, you wonder how much any foreigner can explain about the place.

Bolivia, in short, stands apart from all your ideas, much as the Indian women, with their boxes of Windows 98 software and books by the Dalai Lama sit apart from the future that saunters past them on the street. As I walked through the city my first day in La Paz, the vendors in their shacks never once approached me, or shouted anything out, or tried to catch my attention with their wares. They simply sat where they were, as (it was easy to believe) they had sat for centuries. Once, when the sky turned suddenly black and torrential rains began to pelt down on us all, the women got up wordlessly, draped some tarpaulins over their shacks and then sat down again, silent as before. Otherwise, no movement at all.

I had come to La Paz in the middle of its December summer to get away from a world that was preoccupied with the war between the future and the past. As soon as terrorists attacked Manhattan – the global future, as they feared – and Washington responded by attacking the past (the Afghanistan of the Taliban), a war that had been taking place in every household and heart, between the elders who say “Let’s go back” and the young who say “Let’s go forward,” had gone global, in effect. Everyone was asking how much ritual and devotion we needed in the midst of the post-modern MTV swirl.

La Paz, however, seemed to sit outside all such notions. It sat apart from the world, out in its own dimension. Queen Victoria, in fact, once pronounced that Bolivia did not exist after her ambassador in La Paz refused a drink offered him by one of the country’s tyrants and was forced, in response, to drink a barrelful of coffee, then led backwards through the streets on a mule; Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, detective-story writer-turned-spiritualist, set his “lost world” in Bolivia. During the eighties, when all the world watched Washington and Moscow pronounce “mutually assured destruction,” La Paz was said to be the safest place to be in the event of a nuclear crisis.

And even in the midst of all the city’s very real problems – 125 beds, it was estimated, to serve the fifty thousand physically and emotionally disabled people in the local shanty town of El Alto – the people of La Paz seemed to have a very different notion of a “market” economy from the one unveiled by a young, Texas-educated local president, speaking his fluent English on TV. In the week before I arrived in Bolivia, Argentina next door had seen three different presidents in twelve days, and dozens of demonstrators lay dead along its European streets; on the way to La Paz, I had stopped off in Lima and found an angry, swollen metropolis across which people had scrawled cries of rage, and where even the windows on busy avenues were barred.

Like many of the countries of South America, both Peru and Argentina seemed to have been left stuck by the Spanish between a vanished colonial notion of glory and a future that had never arrived; in desperation, often, not fully European and not really themselves, they tried to fill the empty spaces with pomp. Bolivia, by comparison, gave an impression of self-containment: a poor country, yes, but one that never seemed to have expected to get rich.

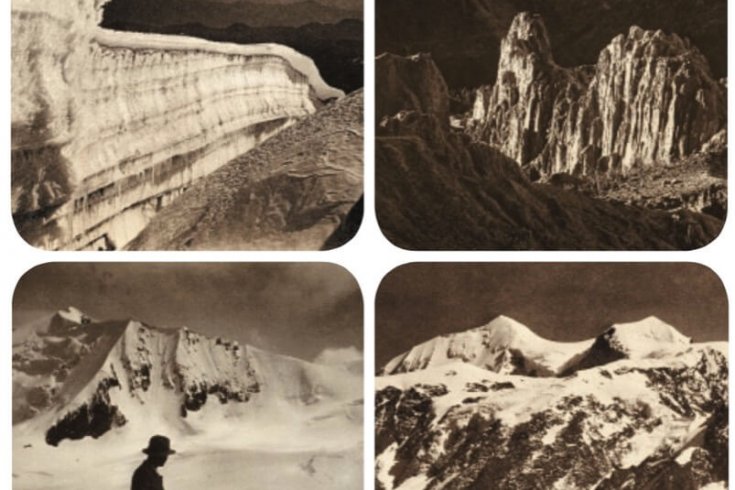

For me, then, Bolivia was enchantment. I drew back the curtains in my room, and saw everything picked out with uncanny sharpness in the summer light. Mountains almost four miles high stood at the end of narrow streets, and at night the whole town glowed with the lights of the little houses around the hills. Even though the El Alto slum I visited one morning was a shocking place, with its corrugated-iron shacks and its unpaved roads, compared with what I was used to seeing, in impoverished Bombay or even in L.A., it did not look so desperate.

The growing stain of huts across the hill, which happen – such is Bolivia’s freedom from conventional logic – to enjoy the best views in the city, is a sobering reminder of what occurs when the countryside swallows up the city and a ragged past comes to claim the future. The walls around me, though not as furious as those in Lima, were inscribed with slogans hardly less poignant – “I do not believe that justice and equality exist”;”We respect those who respect us” – and El Alto, thanks to the floods of rural poor hoping to redeem themselves in the city, has become one of the fastest-growing urban settlements on the continent. Yet still it was hard not to be warmed by the sight of the Ferris wheels and foosball tables that had been set up in the downtown streets or by the sign at the Internet café (in the shape of a Christmas tree) that said, “The Three Wise Men Brought a Scanner!” It is often noted by visitors that Cervantes himself once tried (in vain) to become mayor of La Paz, and he above all might have rejoiced in the fact that even a massage parlour offered an open-hearted message in the national newspaper La Razón as the old year came to an end: “On the occasion of the coming of the New Year, the Flor de Loto offers its distinguished clientele peace, happiness and divine good fortune for the realization of all your dreams and plans.”

The Bolivian, of course, encountering these same scenes, would see something different. One day I stumbled out of my hotel, the Donald Duck cartoons of its breakfast room reeling through my mind and, still a little woozy from the altitude (or from the gallons of coca tea I’d been drinking to offset its effects), walked into a demonstration. The whole central promenade – the present tense, as it had seemed to me at first – was taken over, block after block, by ragged campesinos, shouting out their dissatisfactions, as they would protest selling natural gas to America when bringing down the government this past October. Every few minutes a firecracker went off, and the street was rent with a thunderous explosion. The Indian women, engagingly, cupped their hands behind their ears as if to protect themselves from the moment.

As I stood there, watching the banners marching past – “The Association of Joyless Workers”;”Generation Sandwich” – a shoeshine boy came up to me (an emblem of escape, he might have thought) and confessed his longing to go to America. To get rich? I asked, or to claim freedom? or perhaps to see Britney Spears in person?

“No,” he said. He wanted to kill people with the U.S. Army. His mouth was covered by a scarf, to protect himself from the fumes of the traffic, and it was easy to imagine he was one of the thousands of Bolivian children who could neither read nor write. Some such children actually live with their convict fathers in the local prison and are glad for the relative safety. “It’s so calm here,” I said, thinking of the Lima I’d just come from, the Calcutta and Miami where I often found myself. “Calm?” said the boy. He looked at me as if I were mad.

In the days that followed, I duly visited all the sites mentioned in the guidebooks: the high, lonely emptiness of the Altiplano, as desolate as a pair of panpipes played on a quiet evening; the strange enigmas of Tiahuanaco, one of the great unexcavated mysteries of the world – a few statues looking out on the unbroken plains all around, the sun casting huge shadows across the nearby hills, and the handful of tourists here this New Year’s Eve reduced to stick figures in the distance; the sleepy towns around Lake Titicaca. Yet all these, of course, belonged to the tourist’s Bolivia, and I longed to see how this world looked to the people who actually lived there. On my last day in the country, therefore, I decided to visit the final destination mentioned in my guidebook.

Just three minutes away from the Prado, where children were flying balloons, and a merry-go-round, its cars shaped like the characters of Pokémon, waited to delight them, there stood a large building on a street called Calle Canada Strongest, which looked like an impregnable fortress. I slipped between two handsome façades looking out on the main boulevard, mansions from the nineteenth century, and instantly found myself away from the commotion of the crowds and in front of this monumental place, the San Pedro Prison.

Some convicts here maintain jobs – to support themselves in the prison’s self-sufficient economy – and one inmate, my guidebook pointed out, had decided to put together a living of sorts by offering visitors tours of his new home. San Pedro was said to be a microcosm of the society around it: some people lived in “cells” that were as well-appointed as five-star hotel rooms, while others were squeezed, by the hundred, into spaces originally intended for twenty-five.

When I arrived at the fortress there were only a few young shaven-headed travellers from Israel milling about. I didn’t know whom (or what) to expect of this place, and the other tourists did not seem willing or able to help me, so I stood around with them and waited to see what would follow. An unsmiling man in uniform strode out and shouted, “Hands against the wall.” We felt rough hands patting us down. Then we were told to remain where we were and await further instructions. Already the divisions between the innocent and the criminal were beginning to blur.

We waited perhaps ten minutes in the hot sun and at last two guards came out and led us into a tiny, dark corridor, barred on both ends. A gate clanked shut behind us. In a neighbouring courtyard – we could see throughthe barred windows – prisoners were walking about or standing in front of what looked to be a chapel. Others wandered around with female visitors – girlfriends or wives – and some of them began to open packages brought by mothers or grandmothers.

A little boy was plodding around the small space, his hand in his father’s. The older man was looking down, as if distracted. A young woman, pretty in a T-shirt and new-looking jeans, her tight ponytail swinging behind her, stood under a Sprite sign with two small children, waiting for a husband or a friend. A pay phone sat unused. As we looked out at this bleak situation, a man came up to the bars and started shouting to us in English. “Deny everything!” he said, as if he were a lawyer. “Deny it! If they find anything on you, just deny it! Don’t give them anything!”

There was no room to turn in the narrow space, and the earringed Israelis looked no more comfortable than I was. We were pinned, all twelve of us, in a space large enough for six. Every now and then a door would be opened, someone would be led off, and we would be one fewer. But still it didn’t feel as if there was any more room. The prisoner outside kept shouting at us, and the armed guards who were in charge looked decidedly unamused by our presence. The whole expedition began to feel like a very bad idea.

As I waited, with nothing else to do – the prisoner (wearing a baseball cap, a gringo, like us, had he been found with drugs?) shouting advice; the guards patrolling the space outside our bars – I began to feel mysteriously guilty: furtive, and in some way soiled. There must be something I had done, I thought, some charge on which they could bring me up; there were any number of irregularities of which I could be accused. The previous day, crossing a small lake in the countryside on a rowboat, I had come to a routine customs check – a little shack in an empty place – and the officers had taken away my passport. So now I was even less official, my formal identity taken away from me.

Around me all the faces I could see were hard, with scars. The gringo, himself disfigured, shouted and shouted as if he were in an asylum where only the sane are taken to be mad. As the minutes wore on and nothing happened – the Israelis as impatient as I in our pen – I began to wonder if I’d inadvertently joined a group of real criminals. After all, I had exchanged no words with them outside the prison; for all I knew, they were not tourists at all but suspects brought in for questioning. What if someone had planted something on me? Or if…. Who knows what could get lost in translation?

I decided to get out. It was a difficult decision, and not a popular one, and the Israeli boys hardly made room for me as I tried to squeeze toward the gate. If coming to the prison on a Sunday morning as a tourist had been a bad idea, suddenly deciding that you should never have come in the first place now appeared an even worse one. My fellow travellers snarled and muttered curses as I pushed past them, pressing up against the bars in the narrow space.

When finally I squeezed by them and out through the door behind which we were penned, the guards looked at me as if I were a prisoner attempting to escape. “What do you want?” they asked silently with upward nods. “I’ve decided to go home,” I said in broken Spanish. Without a word, they moved toward me and pushed me into a tiny cell nearby, equipped with nothing but a bare bed and a bare wall. There were two officers in the room and hardly enough space for any of us to move.

They motioned for me to strip completely, and I readily complied. One of them started prodding my genitals with a truncheon; the other watched to see why I might be trying to let myself out. Told to pick up my clothing and empty the pockets, I began taking out everything I had: my wallet, a comb, some keys, a pen, a handkerchief, a Japanese temple charm I carried around with me for protection.

“Your passport?” asked one of the men, in Spanish.

“No,” I said, “I don’t have it here.”

The other guard picked up the small, inscrutable temple charm – some characters in Japanese written on the pouch – and, poking around in it, found a piece of paper there. I’d never known that the little pocket contained anything. He took it out and began to sniff it. He unfolded it, folded it again, unfolded it. On it was inscribed a Buddhist prayer, I saw now, some words of good luck bestowed on anyone who had bothered to pay for the talisman. But the words were written in a language that none of us could read, and the guard continued to stare. Why did I have this? What were these papers doing inside the little pocket?

I looked around the cell and thought: they could put something else inside the charm now, and then turn around and discover it. They could discover anything they wanted, if they so chose, the way a tourist, confronted with sentences that he doesn’t understand, draws the conclusions, makes the observations that suit him. The contents of my pockets – they might as well have been my entire life – lay scattered across the bed: a bronchial inhaler, a snapshot of a girl I know in Japan, the key to my hotel room. The previous day, at the customs shack, the inspectors had noticed that my height, as listed in my passport, hadn’t been amended since I was a child. They’d looked and looked at me but hadn’t been able to make out the scar listed in the passport as a distinguishing mark.

“It’s okay,” a woman behind me in the line had said. “They think you’re a terrorist.” A few of the men who had flown the planes into the World Trade Towers, she told me, had been planning the assault while staying in cheap hotels here in La Paz. It was the perfect city in which to hide.

This very morning at breakfast, in deference, perhaps, to Camus’s famous dictum – “What gives value to travel is fear” – I’d been reading Graham Greene’s The Ministry of Fear, an exploration of Kafka’s themes that asks, Which of us, if suddenly brought before a tribunal, has an entirely clear conscience? Which of us has nothing at all to hide?

“Deny everything!” the man in the baseball cap shouted in the courtyard outside. “Give me the name of your hotel; I can get your stuff sent back to you. Deny it all, if they find anything on you.” I’d taken him, before, for a friend, or at least the one person in the place who spoke my language; now I wondered what he was saying, and to whom.

“Rapido, rapido,” said a policeman, as his friend sniffed again at the temple charm, truncheon at the ready. “Rapido.” The other man began peeling back the soles of my shoes, first the left one, then the right. Out of my wallet came my credit cards, every banknote I was carrying. Out came my California driver’s licence, my business cards, the list of all my travellers’ cheques. Out came everything I had.

The excitement of travel is that you’re in a place where nothing makes more sense than fragments in a dream: that pretty girl is smiling at you (or at the possibilities you represent), and the light above the snowcaps is exalting. Things have a sharpness in the high clear air they never have at home. The shadow side of travel is that nothing stands to reason: you’ve done nothing wrong, and now you’re a fugitive who looks very much like the ones who came here to bring down the global economy. The cops let me out at last – I was wasting their Sunday morning – and I walked back to my hotel just a few minutes away. I picked up The Ministry of Fear, and then put it down again. Somehow the appetite to read it had gone.

The next day, I flew away from Bolivia, passport retrieved, on a Peruvian plane (the Bolivian jet inert on the runway as though it wanted to keep me there forever), and the whole place began to fall away from me, “like a shining bit of cold light,” as a friend who knew the country had written the previous year, describing how nothing he experienced in Bolivia translated to the world outside.

The plane rose up and up from the highest airport in the world, and when I looked out the window, I saw the enigmatic towers of El Alto, standing sentry above the shacks, the market that made a mockery of straight lines, the shanty town that went on and on as if to swallow up the broad streets and the high-rise buildings of the Prado, the sun burning gold in the skyscrapers’ panes. Down below, in the valley to the South, the condos and the gated palaces were laid down in a straight row next to the rock faces.

But all around the straight lines, I could see now from my aerial perspective, were lunar outcroppings and wild rock formations that showed that this was where the city ended, and this was where the wilderness began again. In Bolivia, as in the California to which I was returning, the rich live very far from town, in places where people perhaps weren’t meant to live at all. In Santa Barbara this meant scorpions occasionally in the kitchen and foxes outside the bedroom door; mountain lions would surely take away the cat if the coyotes didn’t get it first. In La Paz this meant sudden storms that turned the modern streets into rivers of debris as if to recall to humans where they belonged and where they should not stray.

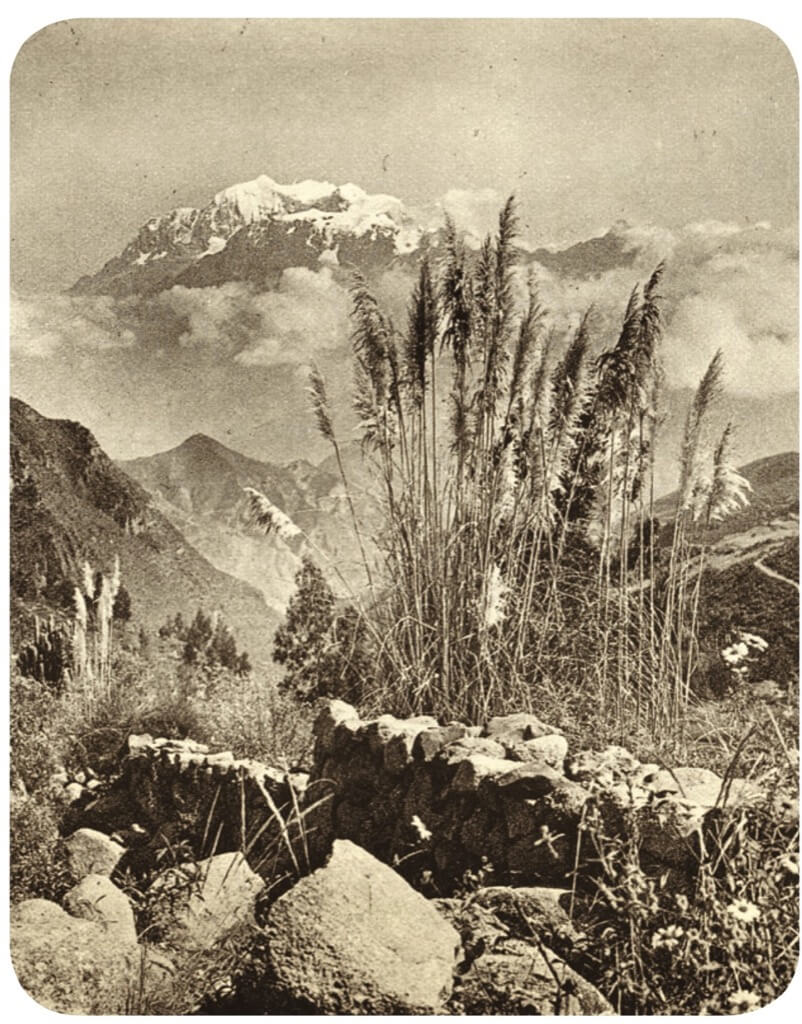

And only then I remembered how, one glorious morning, in a state of high excitement, seeing the light knife-sharp above the mountains, I had hurried out of my hotel and jumped into a cab to go to the Valle de la Luna, the otherworldly collection of salt-coloured pinnacles that form a kind of alternative world ten minutes from downtown La Paz. I’d walked and climbed for an hour or more, up and down amid the jagged peaks and stalagmites, as they seemed – in and out of the unearthly pinnacles, the blue so sharp it took my breath away, and the whole place deserted save for me.

I found a rough path leading over the jutting rock formations, and each turn brought me into a new relation to the peaks, the billowing clouds so white it looked as though they would cry, the sun picking out a light in a far-off window. A landscape of ash and rich blue, as suddenly resolved by summer hailstorms into surging torrents.

I’d returned to the man who’d been kindly waiting for me – “Take as long as you need,” he’d said, as Bolivians often do – and we’d gone back into the city toward the skyscrapers. This was where the heliport was meant to be, he said, pointing to a space on top of a high-rise; these buildings were the future that had been so hopefully erected in the seventies (before 1984, when inflation hit 28,000 percent).

We’d followed the decorated round-abouts into the core of town – “Global Solutions” on one window, BMW showrooms and chic cafés – and arrived at what I’d taken to be the present tense. All around, though, I saw now, was a past so untamed that just to walk around it for a few moments, ten minutes from downtown, was to feel that everything around me – the hotel, the lights I saw out of my window, the conclusions I was beginning to come to – was as fragile as the light, just turning now, beside the sunlit valley, to dark above the mountains.